Poet. Painter. Visionary? William Blake failed to find great success in his lifetime and died in relative obscurity but is now known internationally for his controversial and innovative works in the written word and visual arts.

Blake was born on 28th November, 1757, at 28 Broad Street in Soho, the third son of hosier James Blake and his wife Catherine (he was christened at St James’s Piccadilly). Little is known of his early life although accounts suggest he had some spiritual experiences – including a vision of a tree full of angels – as a young boy and also showed an interest in the visual arts at an early age.

About the age of 10, he started attending Henry Par’s drawing school before, at the age of 14, becoming an apprentice to James Basire, engraver to the Royal Society and Society of Antiquaries. Among his early assignments was to make drawings of the monuments and paintings at Westminster Abbey – interestingly, Blake’s earliest extant drawings are of the opening of King Edward I’s coffin on 2nd May, 1774.

About the age of 10, he started attending Henry Par’s drawing school before, at the age of 14, becoming an apprentice to James Basire, engraver to the Royal Society and Society of Antiquaries. Among his early assignments was to make drawings of the monuments and paintings at Westminster Abbey – interestingly, Blake’s earliest extant drawings are of the opening of King Edward I’s coffin on 2nd May, 1774.

In 1779, his apprenticeship completed, Blake enrolled as a student at the Royal Academy of Arts and at the same time, made his living as a copy engraver. His clients included the radical bookseller Joseph Johnson through whom he became introduced to people like Joseph Priestley. He also began producing original works on historical themes apparently with the aim of forging a career in the painting of history.

In 1782, Blake married Catherine Sophia Boucher and they took up life together at a property near Leicester Square, later moving to Lambeth. They were to have no children.

Experimenting with new methods of engraving, in 1788, he published the first of what he was to call his “illuminated books” – All Religions are One, and There is no Natural Religion – with his first illuminated book of poetry, Songs of Innocence, coming a year later (its sequel Songs of Experience was published in 1794). In 1789, he published The Book of Thel, combining his new method of engraving with “prophetic” verse.

Later works in prose and poetry – created while Blake was still working as an engraver – continued to explore his increasingly radical views on religion and politics. They included The Marriage of Heaven and Hell published in 1790, The French Revolution in 1791, America: A Prophecy in 1793 and Visions of the Daughters of Albion the same year.

In 1800, Blake moved to Felpham, West Sussex, thanks to his friendship with one William Hayley who engaged his skills on several projects. It was while living here that Blake began work on his epic poems Milton (printed in 1810-11) and Jerusalem (completed in 1820).

Following an incident in 1803 in which Blake removed a drunk soldier from his garden, Blake was charged with high treason but acquitted after a trial at Chichester.

Having meanwhile moved back to London, in 1809 Blake made a last effort to gain the public’s attention with his work and held an exhibition of his paintings and watercolours at his family home in Broad Street (now home of his eldest brother James). But the exhibition did not elevate his profile as he may have hoped and during his last years, Blake increasingly sank into obscurity amid tightening finances and, although he continued to produce poetry, paintings and engravings, he found it hard to find work.

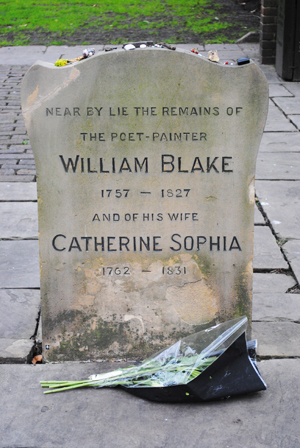

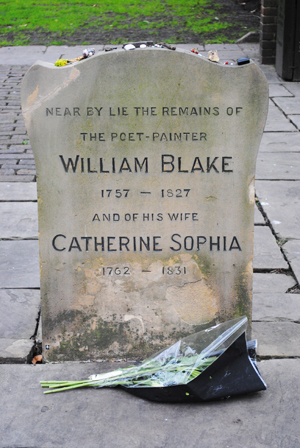

Blake died on 12th August, 1827, at his home at 3 Fountain Court on the Strand and was buried in an unmarked grave at Bunhill Fields. The stone which now stands there (pictured above) was added later.

It was during the Victorian-era that Blake’s work made its way into the hands of a larger audience than it ever had while he was alive, thanks to Blake enthusiasts like his first biographer Alexander Gilchrist and people associated with the Romantic movement.

His work continued to gain attention into the 20th century (in particular around the centenary of his death in 1927) and by mid-century had become what Robert N Essick says in Blake’s entry in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, “one of the cultural icons of the English-speaking world”. Interest in Blake and his works has continued both in the UK and around the world.

A new room dedicated to showing Blake’s works opened at Tate Britain in May.