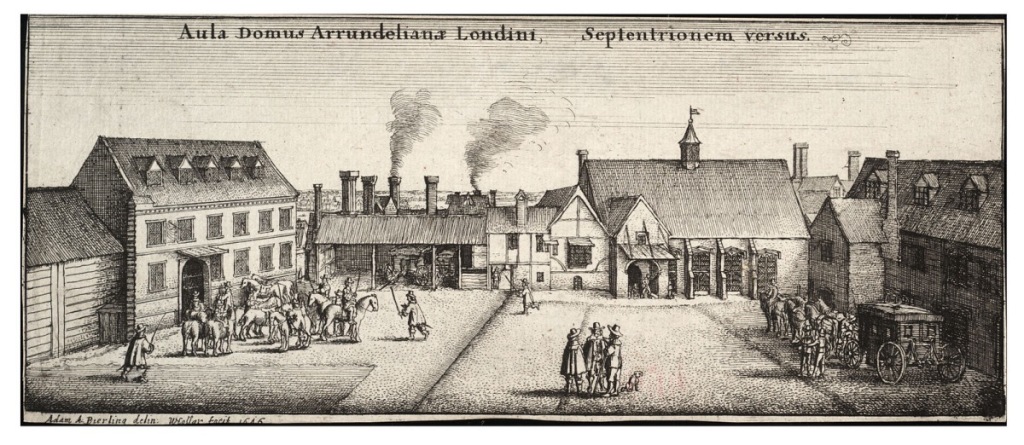

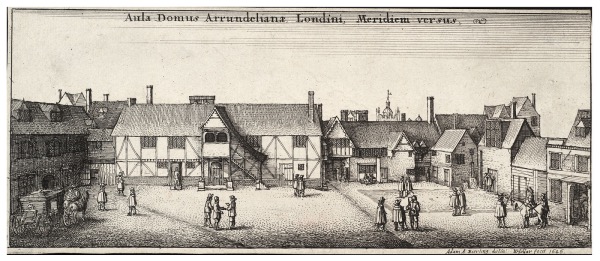

One of a string of massive residences built along the Strand during the Middle Ages, Arundel House was previously the London townhouse of the Bishops of Bath and Wells (it was then known as ‘Bath Inn’ and Cardinal Thomas Wolsey was among those who resided here during this period).

Following the Dissolution, in 1539 King Henry VIII granted the property to William Fitzwilliam, Earl of Southampton (it was then known as Hampton Place). After reverting to the Crown on his death on 1542, it was subsequently given to Thomas Seymour, 1st Baron Seymour of Sudeley, a younger brother of Queen Jane Seymour, Henry VIII’s third wife, and known as ‘Seymour Place’. Then Princess Elizabeth (late Queen Elizabeth I) stayed at the property during this period (in fact, it’s said her alleged affair with Thomas Seymour took place here).

Seymour significantly remodelled the property, before in 1549, he was executed for treason. The house was subsequently sold to Henry Fitz Alan, 12th Earl of Arundel, for slightly more than £40. He was succeeded by his grandson, Philip Howard, but he was tried for treason and died in the Tower of London in 1595. In 1603, the house was granted to Charles, Earl of Nottingham, but his possession was short-lived.

Just four years later it was repurchased by the Howard family – in particular Philip’s son, Thomas Howard, 14th Earl of Arundel – who had been restored to the earldom.

Howard, who was also the 4th Earl of Surrey, housed his famous collection of sculptures, known as the ‘Arundel Marbles’, here (much of his collection, described as England’s first great art collection, is now in Oxford’s Ashmolean Museum).

During this period, guests included Inigo Jones (who designed a number of updates to the property) and artist Wenceslas Hollar who resided in an apartment (in fact, it’s believed he drew his famous view of London, published in 1647, while on the roof).

Howard, known as the “Collector Earl”, died in Italy in 1646. Following his death, the property was used as a garrison and later, during the Commonwealth, used as a place to receive important guests

It was restored to Thomas’ grandson, Henry Howard, 6th Duke of Norfolk, following the Restoration. Following the Great Fire of London in 1666, for several years the property was used as the location for Royal Society meetings.

The house was demolished in the 1678. It’s commemorated today by the streets named Surrey, Howard, Norfolk and Arundel (and a late 19th century property on the corner of Arundel Street and Temple Place now bears its name).

Recorded in the Domesday Book as Putelei and known in the Middle Ages as Puttenhuthe, it apparently goes back to a Saxon named Puttan who lived in the area and the Old English word ‘hyp’, which means ‘landing place’. Hence, “Puttan’s landing place” (or Puttan’s wharf).

Recorded in the Domesday Book as Putelei and known in the Middle Ages as Puttenhuthe, it apparently goes back to a Saxon named Puttan who lived in the area and the Old English word ‘hyp’, which means ‘landing place’. Hence, “Puttan’s landing place” (or Puttan’s wharf).