Now long gone, this central London property was once the residence of the, you guessed it, bishops of Durham.

King Henry VIII

10 London bishop’s palaces, past and present – 3. Winchester Palace…

Now a few scant ruins located in Southwark, this was once the opulent palace of one of the most powerful clergymen in the country.

We’ve written about Winchester Palace before but we thought it was worth a second look in our current series.

Subscribe for just £3 a month to access all of our content…

10 London bishop’s palaces, past and present – 2. York Place…

The precursor to Whitehall Palace, York Place was the London residence of the Archbishops of York between the 13th and 16th centuries.

Subscribe for just £3 a month to access all of Exploring London’s content…

Lost London – The Whitehall Mural…

Known through its many surviving copies, the Whitehall Mural was a dynastic portrait understood to have been created to decorate a privy chamber of King Henry VIII at the Palace of Whitehall.

by Hans Holbein the Younger

ink and watercolour, circa 1536-1537

NPG 4027 © National Portrait Gallery, London (licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 3.0)

The mural, which was the work of Hans Holbein the Younger, featured four figures standing around a central plinth. They include King Henry VIII and his wife Jane Seymour at the front with the King’s parents King Henry VII and Queen Elizabeth of York at the back.

It is believed the portrait, commissioned during the King’s brief marriage to Jane Seymour (between 30th May 1536 and 24th October 1537), may have been created to celebrate the birth of Prince Edward (later King Edward VI) in 1537 and may have been commissioned before or after the prince’s birth.

The iconic image of the bearded King Henry VIII – which was created for the purposes of propaganda – shows him as something of an idealised powerful monarch with feet firmly planted apart and his arms out with a dagger hanging at his waist.

The mural was lost when a fire consumed much of the palace on 4th January, 1698. But copies – both of the mural as a whole and of the individual figure of King Henry VIII – survive including one by Flemish artist Remigius van Leemput commissioned by King Charles II the year before the fire.

There’s also a full-sized cartoon (pictured) showing the left-hand section of the mural which was created by Holbein in preparing to create the mural. Depicting King Henry VIII – his head turned in a slightly different aspect to the final version – and King Henry VII, it would been used to mark out the mural on the wall where it stood.

This Week in London – The story of Henry VIII’s lost dagger; ‘Secret Maps’ at the British Library; and, ‘Connection and Identity’ at Greenwich…

• The disappearance of a jewelled Ottoman dagger which is believed to have once belonged to King Henry VIII has inspired a new exhibition at Strawberry Hill House, Horace Walpole’s former home in Twickenham in London’s west. Henry VIII’s Lost Dagger: From the Tudor Court to the Victorian Stage looks at the history of the 16th century dagger which, said to have been richly decorated with “a profusion of rubies and diamonds”, was once part of Horace Walpole’s collection. When the collection was sold in 1842, the dagger passed into ownership of the Shakespearean actor Charles John Kean who directed private theatricals for Queen Victoria at Windsor Castle. Kean (1811-1868) pioneered what critics dubbed “living museums” on the Victorian stage by using real artifacts, including the dagger, during performances. But after Kean’s death the dagger vanished without a trace. Dr Silvia Davoli, the principal curator at Strawberry Hill House, launched an investigation to find the dagger and instead found six almost identical daggers scattered around the globe. Two of these daggers – known as the Vienna and Welbeck Abbey examples – are featured in the exhibition alongside reproductions of 18th century materials which related to Walpole’s lost dagger from Yale University’s Lewis Walpole Library. The exhibition can be seen from Saturday until 16th February. Admission charge applies. For more, see www.strawberryhillhouse.org.uk.

• The role maps have played in preserving secrets for the benefit of their creators from the 14th century to the present day is the subject of a new exhibition at the British Library. Secret Maps features more than 100 items ranging from hand-drawn naval charts given to Henry VIII to maps of cable networks used to intercept messages between the world wars; and the satellite tracking technology used by apps today. Among highlights are a map from 1596 attributed to Sir Walter Raleigh on an expedition in search of the mythical city of El Dorado in what is now Guyana in South America; a map produced in 1946 of British India (modern-day India, Pakistan and Bangladesh) with a ‘top secret’ report investigating the potential economic and military impact of partition for the proposed state of Pakistan; one of only two known existing copies of a secret map produced by Ordnance Survey during the General Strike of 1926 amid fears of a public uprising; and a 1927 Cable Map of the world which reveals a global network of censorship stations and was used by the British government to intercept messages sent via submarine and overland cables. Runs until 18th January (and accompanied by a programme of events). Admission charge applies. For more, see https://events.bl.uk/exhibitions/secretmaps.

• Staffordshire-based artist Peter Walker’s large scale interactive artworks, Connection and Identity, can be seen in the Painted Hall at the Old Royal Naval College in Greenwich from Friday. Identity features eight columns suspended within the hall which shift in colour and light while Connection showcases “a dramatic and modern reinterpretation of Michelangelo’s Creation of Adam“. The installation, which is located in the hall sometimes described as “Britain’s Sistine Chapel”, is accompanied by music specially composed by David Harper. Runs until 25th January. Admission charge applies. For more, see https://ornc.org/whats-on/connection-and-identity/.

Send all items for inclusion to exploringlondon@gmail.com.

10 places to encounter London’s animal life…4. Bushy Park…

Famous for its herd of Red and Fallow deer, the expansive Bushy Park in south-west London is also a haven for many other kinds of wildlife – from birds and fish to insects and small mammals.

Subscribe now for access to all Exploring London’s stories and support our work!

(In)famous Londoners – Alice Tankerville…

The only woman prisoner recorded as having escaped from the Tower of London, Alice Tankerville was accused, along with her common-law husband John Wolfe, of committing piracy in 1533.

It was alleged that Tankerville had lured two wealthy Italian merchants into a wherry out in the Thames where her accomplices – including Wolfe and two men disguised as watermen – had robbed and murdered them. They were also accused of burgling a home near St Benet Gracechurch where the two men had been staying.

Despite apparently having attempted to seek sanctuary in a special precinct near Westminster Abbey, the couple were arrested, charged with piracy and murder among other things, and, following a trial neither apparently attended, found guilty.

Taken to the Tower of London in 1534 (Wolfe had done a previous stint there for the theft of 366 gold crowns from a ship berthed at the Hanseatic League’s Steelyard but had eventually been released due to a lack of evidence), Alice is said to have been imprisoned in Coldharbour Gate.

Alice wasn’t done yet, however. On 23rd March that year, she managed to escape, apparently with the aid of gaoler John Bawde who provided her with ropes and a key.

It was a short-lived liberation – believed to have been wearing man’s clothes, she and Bawde were arrested trying to reach waiting horses on a road just outside the Tower (it’s worth noting that not only was Alice the only women prisoner to ever escape the Tower of London, she was also the only escapee during the reign of King Henry VIII).

Both she and Wolfe were subsequently executed and due to the nature of their crime, their execution took place on the Thames.

They were hanged in chains in the Thames near the site of their crime and, before a small flotilla of boats filled with sight-seers come to witness the event, were slowly drowned as the tide rose. Their bodies were then left hanging on the spot as a warning to others.

10 towers with a history in London – 10. The ‘Lollard’s Tower’, Lambeth Palace…

This 15th century tower can be found at the north-west corner of Lambeth Palace, London residence of the Archbishop of Canterbury.

Subscribe for just £3 a month to gain access to all our stories – that’s less than the price of a cup of coffee!

Treasures of London – The Abraham Tapestries, Hampton Court Palace…

Hanging in the Tudor Great Hall at Hampton Court Palace, this series of 10 huge tapestries are believed to have been commissioned by King Henry VIII and were first hung in the hall in 1546.

To see the rest of this post (and all of our coverage), subscribe for just £3 a month. This small contribution – less than the cost of a cup of coffee – will help us continue and grow our coverage. We appreciate your support!

This Week in London – West Ham Park celebrates its 150th; rare examples of 17th century paper-cutting; King Henry VIII jousts at Hampton Court; the collection of Elizabeth Legh; and, ‘Horrible Science’…

• West Ham Park celebrates its 150th anniversary this weekend with a festival of music, food, sport, and other activities. On Saturday there will be a free, family-friendly festival with music – including appearances by Australian-born singer-songwriter Celina Sharma and singer-songwriter, Fiaa Hamilton, as well as a DJ set from Ellis – along with arts and crafts, a children’s fun fair and local food stalls. On Sunday, activities are based around the theme of ‘give it a go’ with visitors able try out various sports and health activities, including football, cricket, tennis, athletics, Tai Chi, and long-boarding. There will also be free taster sessions and opportunities to meet local sporting legends. An outdoor exhibition about the park’s history can be seen in Guildhall Yard in the City leading-up to the event after which it will be moved to Aldgate Square. West Ham Park is the largest green space in the London Borough of Newham and has been managed by the City of London Corporation since 1874. Activities on both days start at 12pm. For more, see www.cityoflondon.gov.uk/westhampark150.

To see the rest of this post (and all of our coverage), subscribe for just £3 a month. This small contribution – less than the cost of a cup of coffee – will help us continue and grow our coverage. We appreciate your support!

This Week in London – ‘The Tudor World’ explored; ‘Crossing Borders’ at the Horniman; and, TfL deal at the Painted Hall…

• The oldest surviving rooms at Hampton Court Palace – the Wolsey Rooms which King Henry VIII and Thomas Wolsey once used – are the location of a new display opening today exploring the early years of Henry VIII’s reign and the lives of the ‘ordinary’ men and women who shaped the Tudor dynasty. The Tudor World has, at its centre, rare surviving paintings from the Royal Collection including The Embarkation of Dover – depicting the Tudor navy – and The Field of Cloth of Gold which details Henry VIII’s summit with King Francis I of France in 1520. Also on show is a gold ring believed to have belonged to the Boleyn family, a brightly coloured silk hat linked to King Henry VIII, Wolsey’s portable sundial, a wooden chest used to hide religious contraband by Catholic priests during the reign of Queen Elizabeth I, and, an original Tudor chain pump used to help empty the Hampton Court cesspool. Among the stories of “ordinary” Tudor people being shared is that of Anne Harris, Henry VIII’s personal laundry woman who washed the bandages for his leg ulcers and, Jacques Francis, a free-diver from West Africa who was involved in the expedition to salvage guns from the sunken Mary Rose and who later became one of the first Black African voices heard in an English court, when he was called to testify in a case concerning his employer, Paulo Corsi. Included in palace admission. For more, see www.hrp.org.uk/hampton-court-palace/.

• Crossing Borders, a day of free activities, performances and workshops run by local newly arrived people, will be held at the Horniman Museum Gardens in Forest Hill this Saturday. The day will feature arts and crafts workshops led by IRMO, dance performances by Miski Ayllu and the Honduran Folkloric Pride Group, the chance to learn circus skills with young people from Da’aro Youth Project and South London Refugee Association, and the opportunity to make kites with Southwark Day Centre for Asylum Seekers. The free event runs from 11am to 4pm. For more, see https://www.horniman.ac.uk/event/crossing-borders/.

• Transport for London customers can save 30 per cent on entry to the Painted Hall at the Old Royal Naval College when using the TfL network until 17th November. Simply show customers show your TfL journey on the day of your visit via the TfL Oyster and Contactless app and receive the discount, taking the adult entry price, when booked online to just £11.55. For bookings, head to https://londonblog.tfl.gov.uk/2022/07/27/in-the-city/.

Send all items for inclusion to exploringlondon@gmail.com.

10 significant (and historic) London trees…4. The Royal Oak, Richmond Park…

Estimated to be more than 750-years-old, the tree known as the Royal Oak is located near Pen Ponds and Richmond Gate.

This massive English oak (Quercus robur), which is hollow, doesn’t have any direct connections to royalty but it did survive the felling of trees which took place in Richmond Park and across the south-east of England so King Henry VIII’s navy could be built.

That may have been thanks to the King himself, who wisely passed a law to spare every 10th tree in the park for future seed.

While the park had been used by King Henry VIII as a hunting ground, it wasn’t until 1637 – during the reign of King Charles I – that it was first enclosed.

The tree, which is said to be one of 1,400 “veteran trees” in the park, was pollarded for several hundred years which helped create its shape – this is a method of pruning which removes the top-most branches to form a denser head (and creates wood which can be used for a variety of purposes).

WHERE: Near Pen Ponds, Richmond Park; WHEN: 24/7 pedestrian access; COST: Free; WEBSITE: www.royalparks.org.uk/visit/parks/richmond-park

10 significant (and historic) London trees…1. Queen Elizabeth’s Oak, Greenwich…

Spring is upon us, so we thought it an appropriate time to consider some of London’s greatest natural assets – its trees. But, as well as being significant for their environmental impact, each of these trees (or, in some cases, the remains of them), are significant for historic reasons (we’ve previously mentioned a couple including what’s believed to be the oldest tree and the unusual – and sadly now deceased – Hardy Tree).

First up, it’s the tree known as Queen Elizabeth’s Oak in Greenwich. Thought to date from possibly as far back as the late 13th century, this tree survived until the 19th century before its carcass finally fell to the ground during a storm in 1991. It has lain in Greenwich Park ever since.

The tree, which is located at the end of what is now Lover’s Walk close to the Maze Hill Gate, was located in the grounds of Greenwich Palace (also known as the Palace of Placentia) and was there when King Henry VIII resided at the palace.

In fact, it’s said that he and Anne Boleyn danced around the oak while courting, and (and here’s where the name comes from) that Elizabeth, their daughter (and later Queen Elizabeth I), picnicked under its canopy (some accounts suggest she actually picnicked in the tree’s hollow – but still then upright – trunk).

Following the creation of what is now Greenwich Park, the hollow tree was apparently used as a prison for those caught illicitly on the grounds. They were secured behind a heavy wooden door fitted to the trunk (a park keeper’s lodge was built nearby in the 17th century; it was demolished in the 1850s).

The tree, one of 3,000 in the park, had died in the 19th century and was reduced to an eight metre high stump, partly supported by ivy, when it was blown over by the storm in June, 1991.

A replacement oak, which was donated by the Greenwich Historical Society was planted nearby by the Duke of Edinburgh on 3rd December, 1992, to mark Queen Elizabeth II’s 40 years on the throne.

A ring analysis carried out on the tree found in 2014 it dated back to at least 1569 but with the core missing a precise date of germination couldn’t be found. Estimates, however, place the date of germination to the last 13th or early 14th century. The analysis placed the tree’s death to between 1827 and 1842.

The tree is marked with a plaque and both it and the new tree are surrounded by an iron railing.

WHERE: Queen Elizabeth Oak, Greenwich Park (nearest DLR station is Greenwich); WHEN: 6am to 8pm daily; COST: Free; WEBSITE: https://www.royalparks.org.uk/visit/parks/greenwich-park.

This is an expanded version of a post first made in 2017.

10 atmospheric ruins in London – 9. Barking Abbey…

Once one of the most important nunneries in the country, Barking Abbey was originally established in the 7th century and existed for almost 900 years before its closure in 1539 during King Henry VIII’s Dissolution.

The abbey was founded by St Erkenwald (the Bishop of London between 675 and 693) for his sister St Ethelburga who was the first abbess.

In the late 900s, St Dunstan, the Archbishop of Canterbury introduced the Rule of St Benedict at the nunnery.

King William the Conqueror stayed here after his coronation while famous abbesses included Mary Becket, the sister of St Thomas Becket, Archbishop of Canterbury, who was given the title in 1173 in reparation for the murder of her brother, as well as several royals including Queen Maud, wife of King Henry I, and Matilda, wife of King Stephen.

The nunnery gained wealth and prestige but this suffered somewhat as a result of floods in 1377 with some 720 acres of land permanently lost. It nonetheless remained one of the wealthiest in England and it’s said the abbess had precedence over all other abbesses in the country.

After the abbey was dissolved, some of the building materials were reused elsewhere and the site was later used as a farm and quarry.

Most of the buildings were demolished – today only the Curfew Tower, which dates from around 1460, remains. The Grade II*-listed tower contains the Chapel of the Holy Rood and now serves at the gateway to the nearby St Margaret’s Church.

Building footings also remain buried under the ground in what is known today as Abbey Green (the layout is marked today by modern additions). There’s a model of how the abbey once appeared inside the gateway.

Barking Abbey ruins, Abbey Road, Barking (nearest Tube Station is Barking); WHEN: Daily: COST: Free; WEBSITE: https://www.lbbd.gov.uk/find-your-nearest/barking-abbey-ruins

10 atmospheric ruins in London – 4. Spitalfields Charnel House…

Located under glass beneath a modern square just to the north-east of the line of the City of London’s walls are the ruins of a medieval building which once held human bones.

Built on what had originally been a Roman burial ground, the medieval hospital known as St Mary Spital was constructed towards the end of the 12th century and a graveyard was located on the site for the burial of those who died there.

A small chapel was built on the site in about 1320, the crypt of which became a charnel house housing the bones of those remains disturbed when

The hospital, which had been run by Austin canons, was dissolved by King Henry VIII in 1539 and most of the bones removed. The crypt was later used as a house which was demolished around 1700 and later lost between the gardens of terraced houses.

The remains of the charnel house was discovered in the late 1990s during excavation works – complete with some 10,000 skeletons – and now lies under a glass floor in Bishop’s Square just to the west of Spitalfields Market (it can also be seen through a glass window in the basement level accessed via stairs in the square).

Two statues can be seen inside the ruins – a greenish figure crouching over a prone purple-red figure. Installed in 2014, they are the work of David Teager-Portman and are called Choosing the Losing Side and The Last Explorer.

Spitalfields Chapel and Charnel House, Bishops Square, London, Spitalfields (nearest Tube station is Liverpool Street; nearest Overground is Liverpool Street and Shoreditch High Street).

What’s in a name?…Chalk Farm…

This area in London’s north was recorded as far back as the 13th century when it was known Chaldecote, meaning “cold cottages”.

It’s been suggested that the name may have referred to accommodation for travellers who were travelling up to Hampstead.

The area was part of the prebendal manor of Rugmere and was gifted to Eton College by King Henry VIII in the 15th century.

The area was still farmland by the 17th century and what was then known as Upper Chalcot Farm was located at the end of what’s now England’s Lane. At Lower Chalcot was an inn known as the White House (apparently for its white-washed walls) – believed to have been built on the site of the original manor house.

By the 18th century, the farm was known as Chalk House Farm (apparently a corruption of Chalcot). The Chalk Farm Tavern was built on the site in the 1850s and was a popular entertainment venue which featured tea gardens (and in more recent times was a restaurant).

The area, which had been a popular site for duelling, underwent development from the 1820s – some of the street names, such as Eton Villas and Provost Road reflect the area’s relationship with Eton College.

This development received a considerable boost in the early 1850s when the London to Birmingham railway had its London terminus in Chalk Farm (it’s now Primrose Hill Station). The former railway building known as the Roundhouse is a legacy of the railway’s arrival.

Chalk Farm became part of the London Borough of Camden in the 1960s.

London pub signs – Aragon House…

This brown brick pub (and boutique hotel) in Parson’s Green, west London, was built just after the start of the 19th century. But its name comes from a much earlier historic connection.

The site where the four storey pub now stands was once a dower house which belonged to Queen Catherine of Aragon, the first wife of King Henry VIII.

It’s believed that the property was given to Catherine by King Henry VII, father of her first husband, Prince Arthur – who died in April, 1502 – and her second husband and his younger brother, King Henry VIII, whom she married in 1509.

The site was later part of a parcel of land upon which was located the home of novelist Samuel Richardson. Richardson, famed for his works Pamela and Clarissa, lived there from 1756 until his death in 1761. The property was subsequently known as ‘Richardson’s Villa’.

The Grade II-listed pub is located at 247 New King’s Road. For more, see www.aragonhousesw6.com.

8 locations for royal burials in London…7. Westminster Abbey (near the High Altar)…

We return to Westminster Abbey for the location of yet another royal tomb – this time that of another of King Henry VIII’s wife, Anne of Cleves.

Anne, who lived in England for some 17 years after her marriage to King Henry VIII was annulled after just six months in July, 1540, died at Chelsea on 17th July, 1557, during the reign of Queen Mary I (she was the last of King Henry VIII’s wives to die).

Queen Mary ordered her funeral to be held at Westminster Abbey and she was laid to rest on the south side of the high altar. The unfinished stone monument, believed to have been the work of Theodore Haveus of Cleves, features carvings which depict her initials AC with a crown. There are also depictions of lions’ heads and skulls and crossed bones (believed to represent the idea of mortality).

An inscription on the back of the tomb was added in the 1970s. It can be viewed from the south transept and reads: “Anne of Cleves Queen of England. Born 1515. Died 1557” but this was not added until the 1970s.

HERE: Lady Chapel, Westminster Abbey (nearest Tube stations are Westminster and St James’s Park); WHEN: Times vary – see the website for details; COST: £27 adults/£24 concession/£12 children (discounts for buying online; family rates available); WEBSITE: www.westminster-abbey.org

Famous Londoners – Will Somers…

The most famous of court jesters during the reign of King Henry VIII, little is known of Will Somers’ early life although it is suggested he was born in Shropshire.

It’s said Somers (also spelt Somer or Sommers) entered the service of a wealthy Northamptonshire merchant Sir Richard Fermor who presented him to King Henry VIII at Greenwich in 1525 (he is known to have been in service by 1535).

Somers’ role as jester involved using his wit to comment on court life and those in it – including the likes of Cardinal Wolsey – and while he was permitted a wide latitude he would over-step including when he insulted Queen Anne Boleyn and her daughter Princess Elizabeth, leading to the King to threaten to kill Somers himself.

Somers was provided with royal livery to wear at court (he also sometimes apparently wore elaborate costumes) and was provided with a “keeper” to look after him.

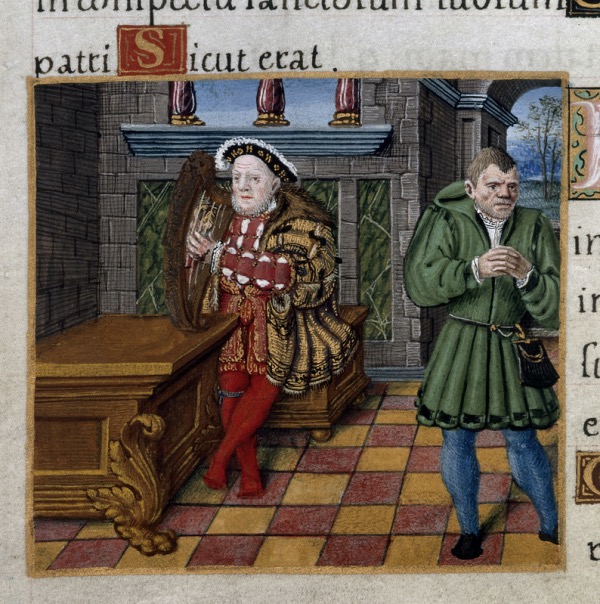

Such was the esteem Somers’ was held in, he is believed to be the fool depicted in a family portrait of the King, his wife Jane Seymour and children Prince Edward and Princesses Mary and Elizabeth (Somers has a monkey on his shoulder in the painting; Jane Foole also appears in the portrait). He’s also believed to be depicted in an image with King Henry VIII which appeared in a psalter (pictured)

Towards the end of King Henry’s life it’s said Somers was the only one who could make him laugh. He remained at court following the King’s death through the reigns of King Edward VI and Queen Mary I and present at the coronation of Queen Elizabeth I, eventually retired during her reign.

Somers is believed to have died on 15th June, 1560, and be buried in St Leonards, Shoreditch. There’s now a plaque to Somers there commemorating his burial.

Sommers subsequently appeared in various works of literature in following centuries including in more recent years when he has also appeared in TV shows – including the series The Tudors – as well as various novels including Paul Doherty’s The Last of Days.

This article contains an affiliate link.

10 (lesser known) statues of English monarchs in London…1. King Edward VI at St Thomas’…

In honour of Queen Elizabeth II’s Platinum Jubilee, we have a new series looking at 10 lesser known statues of previous monarchs in London.

We kick off with not one, but actually two, statues of King Edward VI, the son of King Henry VIII and his third queen, Jane Seymour, can be found at St Thomas Hospital in Southwark.

Both of the statues were commissioned to commemorate the king’s re-founding of the hospital – which had been first founded in the 12th century and had been closed in 1540 as part of the Dissolution – in 1551 and which saw the complete rebuilding of the hospital under the stewardship of the hospital’s President, Sir Robert Clayton.

The oldest of the statues, now located outside the north entrance to the hospital’s North Wing on Lambeth Palace Road, was designed by Nathaniel Hanwell and carved from Purbeck limestone by Thomas Cartwright in 1682.

It originally was part of a group – the King standing at the centre holding his raised sceptre surrounded by four figures which were innovative in that they depicted patients of the time – which adorned the gateway to the hospital on Borough High Street.

It was moved when the gate was widened in around 1720 and subsequently occupied several different positions – including spending some time in storage – before eventually, without the surrounding figures, being moved to its current position in 1976. It was designated a Grade II* monument in 1979.

The second of the two statues is a bronze figure in period dress which was created by sculptor Peter Scheemakers in 1737.

It can now be found inside the hospital’s North Wing, having been moved there last century, and like its counterpart, was designated a Grade II* monument in 1979.

The inscription on the front of the plinth describes the King as “a most excellent prince of exemplary piety and wisdom above his years, the glory and ornament of his age and most munificent founder of this hospital” and adds that the statue was erected at the expense of Charles Joye, Treasurer of the hospital.