It’s 100 years ago this year that the British Empire Exhibition was held in Wembley Park.

Located on a more than 200 acre site, the exhibition was designed to showcase the diversity and reach of the empire. It ran for two six-month long summer seasons – first opening on 23rd April, 1924, and running until 1st November that year and then reopening on 9th May, 1925, and running until 1st October.

The opening ceremony, which took place on St George’s Day, was attended by King George V and Queen Mary, and the event, in a first for a monarch, was broadcast on BBC radio.

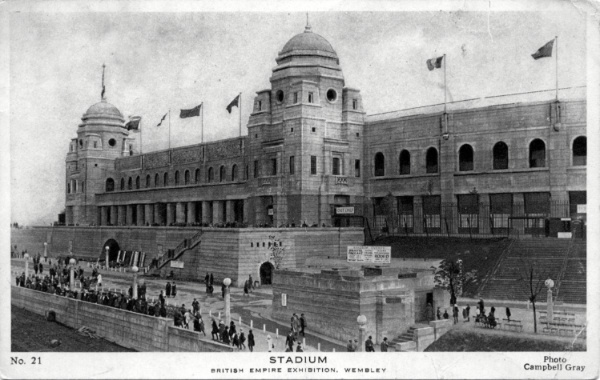

The exhibition, which cost £12 million and attracted some 27 million visitors, featured what was said to be the largest sports arena in the world – Empire Stadium (later known as Wembley Stadium) – as well as four main pavilions dedicated to industry, engineering, the arts and the government, and a series of pavilions for 56 of the empire’s 58 territories as well as some commercial pavilions.

The latter included an Indian pavilion modelled on Jama Masjid in Delhi and the Taj Mahal in Agra, a West African pavilion designed to look like an Arab fort, a Burmese pavilion designed to look like a temple and a Maltese pavilion designed as a fortress with the entrance resembling the famed Mdina Gate.

The Empire Stadium hosted events including military tattoos and Wild West rodeos while other attractions included a lake, a 47 acre fairground, a garden, restaurants and a working replica coal mine.

Star attractions included a replica of King Tutankhamen’s tomb (housed in the fairground), a working model of Niagara Falls and a full-sized sculpture of the Prince of Wales (later Edward VIII) made of butter (both in the Canadian pavilion), a 16 foot diameter ball of wool (Australian pavilion) and dodgem cars (also in the funfair). Queen Mary’s Dollhouse – now housed at Windsor – was designed by Sir Edwin Lutyens and served as a miniature showcase of the finest goods of the period.

Reinforced concrete was the main building material used in its construction, earning it the title of the first “concrete city”. The streets of the exhibition, meanwhile, were named by Rudyard Kipling.

Wembley Park Tube station, which had first opened in 1893, was rebuilt for the event and a new station – Exhibition Station (Wembley) added (it was officially closed in 1969).

While many of the buildings were dismantled after the exhibition, some survived for decades afterwards including, of course, the Empire Stadium which became Wembley Stadium and was the home of English football until replaced in 2003.