Archbishop’s House, located next to the Roman Catholic Cathedral of Westminster, is the official residence of the Catholic Archbishop of Westminster.

Churches

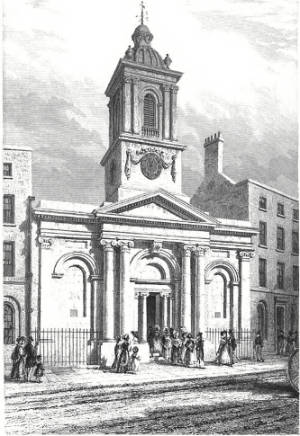

Lost London – Church of St Peter le Poer…

This parish church once stood on the west side of Broad Street in the City of London and dated back to the Norman era.

The church, which originally dated from before 1181 (when it was first mentioned) and was also referred to as St Peter le Poor, may have been so-named because of the poor parish in which it was located or for its connections to the monastery of St Augustine at Austin Friars, whose monks took vows of poverty.

Whatever the reason for its name (and it has been suggested the ‘le Poer’ wasn’t added to it until the 16th century), the church was rebuilt in 1540 and then enlarged in 1615 with a new steeple and west gallery added in the following decade or so.

The church survived the Great Fire of London in 1666 but just over a 100 years later has fallen into such a state of disrepair that parishioners obtained an Act of Parliament to demolish and rebuild it.

The new church, which was designed by Jesse Gibson and moved back off Broad Street further into the churchyard, was consecrated on 19th November, 1792. Its design featured a circular nave topped by a lantern (the curved design was not visible from the street) and placed the altar directly opposite the doorway on the north-west side of the church.

The church had acquired a new organ in 1884 but the declining population in the surrounding area led to its been deemed surplus to requirements. It was demolished in 1907 and the parish united with that of St Michael Cornhill.

Proceeds of the sale were used to build a new church, St Peter Le Poer in Friern Barnet. The new church, which was consecrated on 28th June, 1910, by the Bishop of London, the Rt Rev Arthur Foley Winnington-Ingram, also received the demolished church’s font, pulpit and panelling.

LondonLife I – Marking 80 years since the end of World War II…

Earlier…

What’s in a name?…Upminster…

Known to many as the eastern end of the District Line, Upminster is located some 16.5 miles to the north-east of Charing Cross and is part of the London Borough of Havering.

Historically a rural village in the county of Essex, its name comes from Old English and means a large church or “minster” located on high ground.

The church is said to have dated at least as far back as the 7th century and to have been one of a number founded by St Cedd, a missionary monk of Lindisfarne, in the area. It was located on the site occupied by the current church of St Laurence (parts of which date back to the 1200).

The nearby bridge over the River Ingrebourne shares the name Upminister and is known to have been in existence since the early 14th century.

Once wooded, the area was taken over for farming (cultivation dates as far back as Roman times) and by the 19th century it came to be known for market gardens as well as for some industry including windmills and a brickworks.

Development was initially centred around the minister and nearby villages of Hacton and Corbets Tey. It received a boost in the 17th century when wealthy London merchants purchased estates in the area.

Improved transportation links also helped in later centuries including the arrival of the London, Tilbury and Southend Railway in 1885 – it was extended from Barking – and the underground in 1902 via the Whitechapel and Bow Railway.

Landmarks include the Church of St Laurence, the redbrick Clock House (dating from about 1775), the 16th century house Great Tomkyns, the Grade II*-listed Upminster Windmill, built in 1803 and considered one of England’s best surviving smock mills, and the 15th century tithe barn (once owned by the monks of Waltham Abbey and now a museum).

Upminster Hall, which dates back to the 15th and 16th century (and, once the hunting seat of the abbots of Waltham Abbey, was gifted by King Henry VIII to Thomas Cromwell after the Dissolution), is now the clubhouse of the Upminister Golf Club.

Hornchurch Stadium, the home ground of AFC Hornchurch, is located in the west of the area.

It was in Upminster that local rector Rev William Derham first accurately calculated the speed of sound, employing a telescope from the tower of the Church of St Laurence to observe the flash of a distant shotgun as it was fired and then measuring the time before he heard the gunshot using a half second pendulum.

Treasures of London – Shackleton’s Crow’s Nest…

This barrel-shaped object, which can be found in the church of All Hallows by the Tower in the City of London, was used the crow’s nest on the ship Quest during Sir Ernest Shackleton’s third – and last – Antarctic voyage in the early 1920s.

Subscribe for just £3 a month to access all of Exploring London’s content…

What’s in a name?….Giltspur Street

This City of London street runs north-south from the junction of Newgate Street, Holborn Viaduct and Old Bailey to West Smithfield. Its name comes from those who once travelled along it.

An alternative name for the street during earlier ages was Knightrider Street which kind of gives the game away – yes, the name comes from the armoured knights who would ride along the street in their way to compete in tournaments held at Smithfield. It’s suggested that gilt spurs may have later been made here to capitalise on the passing trade.

The street is said to have been the location where King Richard II met with the leaders of the Peasant’s Revolt who had camped at Smithfield. And where, when the meeting deteriorated, the then-Lord Mayor of London William Walworth, ending up stabbing the peasant leader Wat Tyler who he later captured and had beheaded.

St Bartholomew’s Hospital can be found on the east side of the street. On the west side, at the junction with Cock Lane is located Pye Corner with its famous statue of a golden boy (said to be the place where the Great Fire of London was finally stopped).

There’s also a former watch house on the west side which features a monument to the essayist late 18th century and 19th century Charles Lamb – the monument says he attended a Bluecoat school here for seven years. The church of St Sepulchre-without-Newgate stands at the southern end with the Viaduct Tavern on the opposite side of the road.

The street did formerly give its name to the small prison known as the Giltspur Street Compter which stood here from 1791 to 1853. A prison for debtors, it stood at the street’s south end (the location is now marked with a City of London blue plaque).

10 historic London docks…6. St Mary Overie’s Dock…

This small but historic London dock is located at Bankside on the south bank of the Thames.

Subscribe to get access

Read more of this content when you subscribe today.

Lost London – Gatehouse Prison…

Located in what was the gatehouse of Westminster Abbey, this small prison dates from 1370.

It was built by Walter de Warfield, then the abbey’s Cellarer, and featured two wings, built at right angles to each other.

Under the jurisdiction of the Abbot, the prison had two sections – one for clerics and one for laymen. The Abbey’s Janitor was its warder.

Among the most famous inmates was the Cavalier poet Richard Lovelace who was imprisoned for petitioning to have the Clergy Act 1640 annulled. While inside, he wrote the famous work, To Althea, from Prison which features the famous lines: “Stone walls do not a prison make, Nor iron bars a cage”.

Other notables include Sir Walter Raleigh, held here on the night before he was beheaded in Old Palace Yard on 29th October 1618, diarist Samuel Pepys – detained for a few weeks in 1689 on suspicion of being a Jacobite (but released because of ill health), and Gunpowder Plot conspirator Thomas Bates.

Falling into a state of decay, the prison was demolished in 1776-77 (although one wall stood until the 1830s). A gothic column, the Westminster Scholars’ Memorial which is also known as the Crimea and Indian Mutiny Memorial, now stands on the site.

A Moment in London’s History – The taking of the Stone of Scone…

A rectangular block of pale yellow sandstone decorated with a Latin cross, the Stone of Scone, also known as the Stone of Destiny, long featured in the crowning of Scottish kings. But in 1296, it was seized by King Edward I as a trophy of war.

He brought it back to England (or did he? – it has been suggested the stone captured by Edward was a substitute and the real one was buried or otherwise hidden). In London, it was placed under a wooden chair known as the Coronation Chair or King Edward’s Chair on which most English and later British sovereigns were crowned.

On Christmas Day, 1950, four Scottish nationalist students – Ian Hamilton, Kay Matheson, Gavin Vernon and Alan Stuart – decided to liberate the 152 kilogram stone and return it to Scotland.

The stone broke in two when it was dropped while it was being removed (it was later repaired by a stone mason). The group headed north and, after burying the greater part of it briefly in a field to hide it, the stone was – on 11th April, 1951 – eventually left on the altar of Arbroath Abbey in Scotland.

No charges were ever laid against the students.

It was brought back to the abbey and used in the coronation of Queen Elizabeth II in 1953.

The stone was eventually returned to Scotland in 1996 on the proviso it could be temporarily relocated back to London for coronations and now sits in Edinburgh Castle. It was taken to London temporarily in 2023 for the coronation of King Charles III but has since been returned.

There is a replica of the stone at Scone Castle in Scotland.

Treasures of London – The Anglo-Saxon archway, All Hallows by the Tower…

This rounded arch in the Church of All Hallows is believed to be oldest surviving arch of the Anglo-Saxon period surviving in the City of London.

The arch can be found at the west end of the nave and dates from an earlier church on the site, possibly built as early as the 7th century (the church was later rebuilt and expanded several times, survived the Great Fire in 1666, and was then largely destroyed during the Blitz before being rebuilt and reconsecrated in 1957).

Roman tiles have been reused in the arch’s construction as well as Kentish ragstone and it doesn’t include a keystone.

The arch was fully revealed after a bombing during the Blitz in 1940 brought down a medieval wall and revealed it.

The arch has given some weight to the idea that the Anglo-Saxon church was founded not long after Erkenwald founded Barking Abbey in the 7th century (he went on to become the Bishop of London in 675).

WHERE: All Hallows by the Tower, Byward Street (nearest Tube station is Tower Hill); WHEN: 8am to 5pm Monday to Friday; 10am to 5pm Saturday and Sunday; COST: Free; WEBSITE: https://www.ahbtt.org.uk/

10 London mysteries – 7. The mysterious pyramid of St Anne’s Limehouse…

On first glance, this stone pyramid standing in the churchyard of St Anne’s Limehouse appears to be a grave marker or tomb, albeit a rather unusual one.

Subscribe for just £3 a month to gain access to all Exploring London’s content – and support our work at the same time!

10 London mysteries – 5. The St Pancras walrus…

Archaeologists were excavating the former St Pancras Old Church burial ground ahead of the expansion of St Pancras Railway Station to accommodate the Eurostar in 2003 when they came across a rather unusual coffin.

Subscribe for just £3 a month to access all of Exploring London’s content (and support our work!)

10 London mysteries – 2. Who was Jimmy Garlick?

This week we look at a mysterious mummified figure who was “discovered” in the vaults beneath the floor of St James Garlickhythe in the 1850s.

Subscribe to Exploring London for just £3 a month and get access to every article (and help us maintain and develop the site at the same time)!

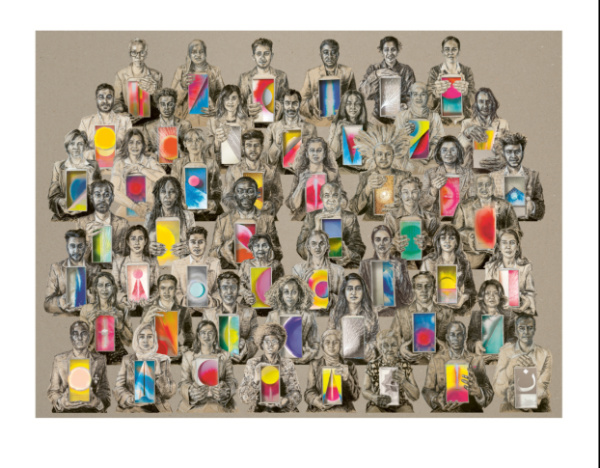

LondonLife – ‘CONGREGATION’ at St Mary Le Strand…

CONGREGATION, a new large-scale installation by Es Devlin, can be seen at the church of St Mary Le Strand – but you’ll have to be quick, it’s only there for two more days (until 9th October). The work, curated by Ekow Eshun, was created in partnership with UK for UNHCR, the United Nations Refugee Agency, and was developed in collaboration with King’s College London and The Courtauld. Created over four months, it features chalk and charcoal portraits of 50 Londoners who have experienced forced displacement from their homelands. Ranging in age from 18 to 90, these “co-authors” have roots in countries ranging from Syria to Sri Lanka; from Rwanda to Albania. An accompanying soundscape has been composed by Polyphonia and features the voices of the sitters while film sequences have been created in collaboration with filmmaker Ruth Hogben and choreographer Botis Seva. CONGREGATION is free to visit and is open to the public daily from 11am till 9pm with free public choral performances outside the church at 7pm each evening to coincide with Frieze London. To book tickets, head to https://www.unrefugees.org.uk/esdevlin-congregation/.

Where’s London’s oldest…bollard?

London is filled with bollards designed to prevent vehicles, old and new, from travelling where they shouldn’t. And, of course, there’s much debate over which is the oldest.

The oldest may well be a rather rusty looking one in the courtyard outside the Church of St Helen’s Bishopsgate.

In what was a practice replicated elsewhere in the City around the time, it’s apparently made out of the French naval cannon dating from the 18th century.

The cannon’s muzzle end has been embedded into the pavement with the non-loading end sticking up.

Legend says that another cannon bollard, located just outside the Globe Theatre on South Bank, comes from French ships captured at the Battle of Trafalgar. While it is indeed said to be a cannon, many have cast doubt on its origins as coming from Trafalgar.

Correction: We’ve correct the story to say it was the non-loading end sticking up.

10 towers with a history in London – 7. Tower of the former Church of St Mary-at-Lambeth…

Part of the deconsecrated Church of St Mary-at-Lambeth – now the home of the Garden Museum, is a tower which was first built in the 14th century.

Support our work and subscribe for just £3 a month to see all of Exploring London’s content

10 towers with a history in London – 6. Westminster Cathedral campanile…

A well-known landmark in Westminster, the distinctive striped brick and stone campanile of Westminster Cathedral stands 284 feet or 64 metres high.

Building of a Roman Catholic cathedral in Westminster – what would be the largest in England and Wales – was the vision of Cardinal Herbert Vaughan. Construction started in 1895 and was complete eight years later. The campanile was the final part of the building’s structure to be completed.

Conscious that the Gothic Westminster Abbey only a short distance away, architect John Francis Bentley instead designed the cathedral in a neo-Byzantine style and the plans originally included two campanili or bell towers which may have been influenced by those in Venice (it was Cardinal Vaughn who famously said one campanile would be enough for him resulting in just one being built).

The 30 foot square dome-topped tower, like the rest of the building, was constructed of stripes of red brick and Portland stone which reflected existing residential buildings nearby.

Formally known as St Edward’s Tower, it contains the 55cwt St Edward’s Bell (named after St Edward the Confessor) which was a gift of Gwendoline, the Duchess of Norfolk, in 1910. It was cast at the Whitechapel Foundry and bears the inscription, “While the sound of this bell travels through the clouds, may the bands of angels pray for those assembled in thy church. St Edward, pray for England.”

Carved stone eagles surround the apex of the tower – a reference to St John the Evangelist (apparently patron saint of the architect) and the cross on top of the cupola is said to contain a fragment of the True Cross discovered by the Empress Helena in 326 AD.

The campanile famously appears at the end of Alfred Hitchcock’s 1940 thriller, Foreign Correspondent, in a scene in which the bad guy is thrown from the top.

The campanile, which has a lift to the top, is open to the public. Viewing balconies on all four sides of the tower provide 360 degree views of the surrounding city including over the stunning domes of the cathedral itself.

WHERE: The Campanile, Westminster Cathedral (nearest Tube stations are Victoria and St James’s Park); WHEN: 11am to 3:30pm Fridays, Saturdays and Sundays; COST; £6 adults; £12 families (two adults and up to four children); £3 concessions (aged 60+); WEBSITE: https://westminstercathedral.org.uk/tower-viewing-gallery-reopens/

10 towers with a history in London – 2. The tower of St Olave, Old Jewry…

This tower is a survivor and was originally part of the rebuilt Church of St Olave, Old Jewry.

The medieval church, which was apparently built on the site of an earlier Saxon church, originally dated from 12th century. Its name referred to both the saint to whom it was dedicated – the patron saint of Norway, St Olaf (Olave) – and its location in the precinct of the City that was largely occupied by Jews (up until the infamous expulsion of 1290).

The church, which is also referred to as Upwell Old Jewry (this may have related to a well in the churchyard), was the burial place of two former Lord Mayors – mercer Robert Large (William Caxton was his apprentice) and publisher John Boydell (who apparently washed his face under the church pump each morning). Boydell’s monument was later transferred to St Margaret Lothbury.

The church was sadly destroyed in the Great Fire of 1666 but it was among those rebuilt under the eye of Sir Christopher Wren in the 1670s. It’s from this rebuilding that the current tower dates.

At this time, the parish was united with that of St Martin Pomeroy (which had already shared its churchyard and which was also destroyed in the Great Fire).

Wren’s church was eventually demolished in 1887 as moves took place to consolidate church parishes under the Union of Benefices Act – the parish was united with that of St Margaret Lothbury and proceeds from the sale were used to fund the building of St Olave, Monor House. It’s worth noting that a Roman pavement was found on the site after the church demolition.

The tower (and the west wall), meanwhile, survived. The tower was subsequently turned into a rectory for St Margaret Lothbury and later into offices.

Interestingly, the Grade I-listed, Portland stone tower is said to be the only one built by Wren’s office which is battered – that is, wider at the bottom than the top. It’s topped by some obelisk-shaped pinnacles and a weather vane in the shape of a sailing ship which was taken from St Mildred, Poultry (was demolished in 1872).

The tower’s former clock was built by Moore & Son of Clerkenwell. It was removed at the time of the church demolition was installed in the tower of St Olave’s Hart Street. The current clock was installed in 1972.

What’s in a name?…Nunhead…

This district of London, which lies to the south-east of Peckham in the London Borough of Southwark, is believed to owe its name to a local tavern named, you guessed it, the Nun’s Head on the linear Nunhead Green (there’s still a pub there, called The Old Nun’s Head, in a building dating from 1905).

There may well have been actual nuns here (from which the tavern took its name) – it’s suggested that there was a nunnery here which may have been connected to the Augustinian Priory of St John the Baptist founded in the 12th century at Holywell (in what is now Shoreditch).

A local legend gets more specific. It says that when the nunnery was dissolved during the Dissolution, the Mother Superior was executed for her opposition to King Henry VIII’s policies and her head was placed in a spike on the site near the green where the inn was built.

While the use of the name for the area goes back to at least the 16th century, the area remained something of a rural idyll until the 1840s when the Nunhead Cemetery, one of the “Magnificent Seven” cemeteries of Victorian London, was laid out and the area began to urbanise.

A fireworks manufactory – Brocks Fireworks – was built here in 1868 (evidenced by the current pub, The Pyrotechnists Arms). The railway arrived in 1871.

St Antholin’s Church was built in 1877 using funds from the sale of the City of London church, St Antholin’s, Budge Row, which was demolished in 1875. St Antholin’s in Nunhead was destroyed during the Blitz and later rebuilt and renamed St Antony’s (the building is now a Pentecostal church while the Anglican parish has been united with that of St Silas).

There’s also a Dickens connection – he rented a property known as Windsor Lodge for his long-term mistress, actress Ellen Ternan, at 31 Lindon Grove and frequently visited her there (in fact, it has even been claimed that he died at the property and his body was subsequently moved to his home at Gad’s Hill to avoid a scandal).

Nunhead became part of the Metropolitan Borough of Camberwell in 1900. These days, it’s described by Foxtons real estate agency as “a quiet suburb with pretty roads and period appeal”.

London Explained – Royal Peculiars…

A Royal Peculiar is a Church of England parish that is exempt from the jurisdiction of the church diocese or province in which it sits and instead answers directly to the monarch.

The concept of the Royal Peculiar first began to emerge in Anglo-Saxon times and was developed over the following centuries.