Containing a residence for the Bishop of London (although, it has to be said, certainly not traditionally a bishop’s palace), the Old Deanery is located in Dean’s Court, to the south-east of St Paul’s Cathedral.

Great Fire of London

Lost London – Church of St Peter le Poer…

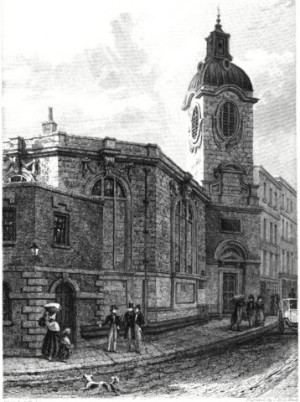

This parish church once stood on the west side of Broad Street in the City of London and dated back to the Norman era.

The church, which originally dated from before 1181 (when it was first mentioned) and was also referred to as St Peter le Poor, may have been so-named because of the poor parish in which it was located or for its connections to the monastery of St Augustine at Austin Friars, whose monks took vows of poverty.

Whatever the reason for its name (and it has been suggested the ‘le Poer’ wasn’t added to it until the 16th century), the church was rebuilt in 1540 and then enlarged in 1615 with a new steeple and west gallery added in the following decade or so.

The church survived the Great Fire of London in 1666 but just over a 100 years later has fallen into such a state of disrepair that parishioners obtained an Act of Parliament to demolish and rebuild it.

The new church, which was designed by Jesse Gibson and moved back off Broad Street further into the churchyard, was consecrated on 19th November, 1792. Its design featured a circular nave topped by a lantern (the curved design was not visible from the street) and placed the altar directly opposite the doorway on the north-west side of the church.

The church had acquired a new organ in 1884 but the declining population in the surrounding area led to its been deemed surplus to requirements. It was demolished in 1907 and the parish united with that of St Michael Cornhill.

Proceeds of the sale were used to build a new church, St Peter Le Poer in Friern Barnet. The new church, which was consecrated on 28th June, 1910, by the Bishop of London, the Rt Rev Arthur Foley Winnington-Ingram, also received the demolished church’s font, pulpit and panelling.

What’s in a name?….Giltspur Street

This City of London street runs north-south from the junction of Newgate Street, Holborn Viaduct and Old Bailey to West Smithfield. Its name comes from those who once travelled along it.

An alternative name for the street during earlier ages was Knightrider Street which kind of gives the game away – yes, the name comes from the armoured knights who would ride along the street in their way to compete in tournaments held at Smithfield. It’s suggested that gilt spurs may have later been made here to capitalise on the passing trade.

The street is said to have been the location where King Richard II met with the leaders of the Peasant’s Revolt who had camped at Smithfield. And where, when the meeting deteriorated, the then-Lord Mayor of London William Walworth, ending up stabbing the peasant leader Wat Tyler who he later captured and had beheaded.

St Bartholomew’s Hospital can be found on the east side of the street. On the west side, at the junction with Cock Lane is located Pye Corner with its famous statue of a golden boy (said to be the place where the Great Fire of London was finally stopped).

There’s also a former watch house on the west side which features a monument to the essayist late 18th century and 19th century Charles Lamb – the monument says he attended a Bluecoat school here for seven years. The church of St Sepulchre-without-Newgate stands at the southern end with the Viaduct Tavern on the opposite side of the road.

The street did formerly give its name to the small prison known as the Giltspur Street Compter which stood here from 1791 to 1853. A prison for debtors, it stood at the street’s south end (the location is now marked with a City of London blue plaque).

10 London mysteries – 2. Who was Jimmy Garlick?

This week we look at a mysterious mummified figure who was “discovered” in the vaults beneath the floor of St James Garlickhythe in the 1850s.

Subscribe to Exploring London for just £3 a month and get access to every article (and help us maintain and develop the site at the same time)!

10 towers with a history in London – 2. The tower of St Olave, Old Jewry…

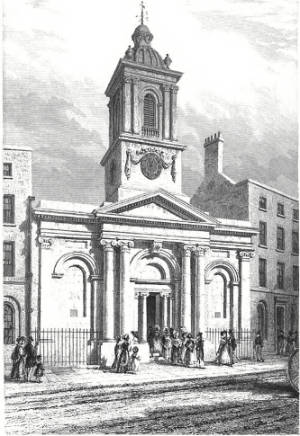

This tower is a survivor and was originally part of the rebuilt Church of St Olave, Old Jewry.

The medieval church, which was apparently built on the site of an earlier Saxon church, originally dated from 12th century. Its name referred to both the saint to whom it was dedicated – the patron saint of Norway, St Olaf (Olave) – and its location in the precinct of the City that was largely occupied by Jews (up until the infamous expulsion of 1290).

The church, which is also referred to as Upwell Old Jewry (this may have related to a well in the churchyard), was the burial place of two former Lord Mayors – mercer Robert Large (William Caxton was his apprentice) and publisher John Boydell (who apparently washed his face under the church pump each morning). Boydell’s monument was later transferred to St Margaret Lothbury.

The church was sadly destroyed in the Great Fire of 1666 but it was among those rebuilt under the eye of Sir Christopher Wren in the 1670s. It’s from this rebuilding that the current tower dates.

At this time, the parish was united with that of St Martin Pomeroy (which had already shared its churchyard and which was also destroyed in the Great Fire).

Wren’s church was eventually demolished in 1887 as moves took place to consolidate church parishes under the Union of Benefices Act – the parish was united with that of St Margaret Lothbury and proceeds from the sale were used to fund the building of St Olave, Monor House. It’s worth noting that a Roman pavement was found on the site after the church demolition.

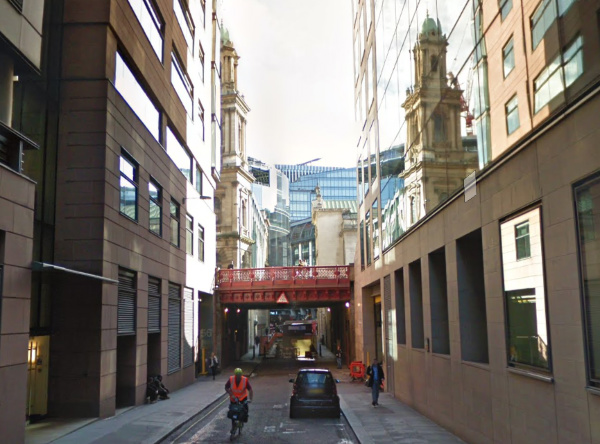

The tower (and the west wall), meanwhile, survived. The tower was subsequently turned into a rectory for St Margaret Lothbury and later into offices.

Interestingly, the Grade I-listed, Portland stone tower is said to be the only one built by Wren’s office which is battered – that is, wider at the bottom than the top. It’s topped by some obelisk-shaped pinnacles and a weather vane in the shape of a sailing ship which was taken from St Mildred, Poultry (was demolished in 1872).

The tower’s former clock was built by Moore & Son of Clerkenwell. It was removed at the time of the church demolition was installed in the tower of St Olave’s Hart Street. The current clock was installed in 1972.

Lost London – St Benet Fink…

This unusually named church dates back to at least the 13th century and stood on what is now Threadneedle Street.

St Benet is a contraction of St Benedict (he who founded monastic communities in Italy in the 6th century) and this was once of four City churches dedicated to the saint before 1666. The word ‘Fink’, meanwhile, is a corruption of Finch and apparently referred to Robert Finch (or Fink) who paid for a rebuild of the church in the 13th century.

The medieval rectangular church was among those destroyed in the Great Fire of 1666. Rebuilding commenced soon after, thanks in part to a £1,000 donation from a Catholic George Holman (he was rewarded with two pews and a place in the vault). The church was completed in 1675 apparently for a cost at just over £4,000.

Designed by Sir Christopher Wren, the church – due to the irregular shape of the site after the City decided to widen Threadneedle Street, was rebuilt on a decagonal plan, over which sat a dome, with a tower at the west end topped by a bell cage over which sat a ball and cross (apparently this latter feature was unique for a Wren church).

The church survived until the mid-18th century when the Corporation of London petitioned Parliament for permission to demolish the tower of St Benet Fink in order make way for an expanded Royal Exchange (which had burned down in 1838).

Following the demolition of the tower (over which there were some protests), a new entrance was cut into the west wall of the church but it proved less than ideal and the City of London was granted permission to knock down the rest of the church which took place in 1846.

The parish was merged with that of St Peter le Poer. Proceeds of the sale of the site were used to build St Benet Fink Church, Tottenham.

The furniture was sold off and paintings of Moses and Aaron that had formed part of the altarpiece are now in the chapel of Emanuel School in Battersea.

Famous associations include John Henry Newman, the future Catholic cardinal, who was baptised in the church on 9th April, 1801.

An office block now occupies the site. A City of London blue plaque marks the site.

What’s in a name?…Basinghall Street…

This City of London street, which sits on the eastern side of the Guildhall complex, is named for the wealthy Basing (or Bassing) family who had a hall here in the 13th century.

The street, which links Gresham Street in the south to Basinghall Avenue in the north, has been the site of numerous prominent buildings including the medieval hall of the Weaver’s Company (demolished in 1856, having replaced an earlier hall which burnt down in the Great Fire of London in 1666, the hall is now located in Gutter Lane), the Cooper’s Company (demolished in 1867, the hall is now located in Devonshire Square) and the Girdler’s Company (destroyed in the Blitz in 1940; the hall is now located in Basinghall Avenue).

It was also the location of the Sir Christopher Wren-designed Church of St Michael Bassishaw until 1899 after it was seriously damaged when the crypt was being cleared of human remains in line with the orders of City authorities. The parish with united with St Lawrence Jewry.

Famous denizens included the goldsmith, banker and civil engineer Sir Hugh Myddelton, most renowned for his design of the New River scheme to bring clean water to the City, who, according to The London Encyclopaedia, would sit in the doorway of his office and smoke his pipe while chatting with the likes of Sir Walter Raleigh.

The family also gave their name to the City of London’s Bassishaw Ward.

What’s in a name?…Pudding Lane…

Famous for being the location of the bakery where the Great Fire of London started, Pudding Lane runs between Eastcheap and Lower Thames Street in the City of London.

While it has been claimed in the past that the name did come from desserts or puddings being sold here, it’s now generally believed that the name relates to the medieval word ‘pudding’ which meant offal – the guts or entrails of animals.

It was apparently down this lane that the butchers of the Eastcheap market (London’s primary meat market in medieval times, located at the northern end of the lane), having slaughtered an animal for consumption, would have the ‘puddings’ carried down the lane so they could be disposed of on waste barges (earlier on, the butchers were apparently permitted to toss the offal into the Thames when tide conditions were right).

The lane, which 16th century historian John Stow said was also known as Rother Lane (due to a Thames wharf called Rothersgate at its southern end) and Red Rose Lane (after a shop sign in the lane), also has the honour of being one of the world’s first designated one-way streets.

Famous Londoners – Thomas Dagger…

Thomas Dagger, a 17th century journeyman baker, only became famous rather recently when new research identified him as the first witness to one of the seminal events in London’s history – the Great Fire of 1666.

The research was undertaken by Professor Kate Loveman at the University of Leicester for the Museum of London and will be used to inform its gallery displays when it opens its new site at Smithfield in 2026.

Drawing on letters, pamphlets, legal and guild records, Professor Loveman put Dagger, who worked in Thomas Farriner’s bakery on Pudding Lane, at the centre of the the fire’s origin story.

It’s well-known that the fire began in Farriner’s bakery in the early hours of 2nd September, 1666, and went on to consume some 13,200 homes in the city, leaving some 65,000 people homeless. But reports differ as to who was in the bakery when the fire started.

Among accounts pointing to Dagger being present is a letter from MP Sir Edward Harley who wrote in a letter to his wife that Thomas Farriner’s “man” – a term referring to his servant or journeyman – was woken after in the early hours on 2nd September choking from smoke. He reported that Farriner, his daughter and “his man” then escaped out of an upper window, but his maid died.

Dagger’s name is also found grouped with other Farriner household members among witnesses on a subsequent indictment targeting Frenchman Robert Hubert who was convicted and hanged for starting the fire after making a somewhat dubious confession.

Professor Loveman concludes that, based on her research, Thomas Dagger was the first witness to the Great Fire of London, woken by choking smoke shortly before 2am on 2nd September. Aware of the fire, he then alerted other members of the household before, along with his boss Thomas Farriner, Farriner’s son Thomas Farriner, Jr, and Farriner’s daughter Hanna, escaping by climbing out of an window. An unnamed maid who was in the house did not escape with them and was killed.

Professor Loveman’s research further showed that Dagger arrived in London from Wiltshire in 1655 and was apprenticed to one Richard Sapp for nine years but ended up serving part of that time with Farriner. Soon after the fire, in 1667, he took his freedom and by January the following year had married and had a baby. He went on to establish his own bakery at Billingsgate.

Says Professor Loveman: “It was fascinating to find out more about what happened on that famous night. Although most of the evidence about the Farriners is well known to historians, Thomas Dagger’s role has gone unrecognised. Unlike the Farriners, his name didn’t become associated with the fire at the time. Soon after the disaster, he merges back into the usual records of Restoration life, having children and setting up his own bakery. His is a story about the fire, but also about how Londoners recovered.”

This Week in London – Wren at Work; music moments captured in photographs; and, the RA’s 255th Summer Exhibition…

• A recreation of Sir Christopher Wren’s office while he was working on St Paul’s Cathedral can be seen at the Guildhall Art Gallery from today. The faux 17th century environment, created by Chelsea Construction, will allow visitors to explore the building methods and tools of the age, as well as the daily lives of 17th century diarists including Robert Hooke, John Evelyn and Margaret Cavendish, and a case study of how citizens lost and regained their properties during and after the Great Fire of 1666. A specially commissioned map by artist/cartographer Adam Dant will provide insight’s into Wren’s life and times and will be displayed alongside illustrations by architect George Saumerez-Smith and members of the Worshipful Company of Chartered Architects, a scale model of St Paul’s Dome by students at Kingston University, and stone models from master mason Pierre Bidaud. The Wren at Work exhibition is part of Wren300. Admission is free but booking are recommended. For more, see www.cityoflondon.gov.uk/events/wren-at-work-wren300-exhibition.

• Photographs capturing Pete Townshend’s guitar flying through the air at Madison Square Garden and Noel Gallagher during the making of the video for Wonderwall are just two of the images on show in a new exhibition at the Barbican Music Library. Celebrating the 25th anniversary of music photography collection Rockarchive.com, In The Moment: The Art of Music Photography also features images of everyone from David Bowie to Debbie Harry, Queen, Biggie Smalls, led Zeppelin, Lady Gaga and Amy Winehouse, capturing them in recording sessions at live gigs and at photo shoots. The free exhibition, which opens on Friday, can be seen until 25th September. For more, see www.cityoflondon.gov.au/services/libraries/barbican-music-library. Meanwhile, a bust of Sir Simon Rattle is being unveiled today at the library in tribute to his five decades in classical music. Sir Simon, who has made over 100 recordings. became music director of the Barbican’s resident orchestra, the London Symphony Orchestra, in 2017 and will conclude his tenure this year.

• The Royal Academy’s 255th annual Summer Exhibition opened this week under the theme of ‘Only Connect’ (inspired by a quote from the novel Howards End by EM Forster). Exhibiting artists include British sculptor Lindsey Mendick, Barbados-born painter Paul Dash, American multi-media artist Ida Applebroog, St Lucia born painter Winston Branch, Colombian sculptor Carlos Zapata and British painters Caragh Thuring and Caroline Walker, and Irish fashion designer Richard Malone, who has created a dramatic mobile installation which hangs in the Central Hall. There are also works by Royal Academicians including Frank Bowling, Michael Craig-Martin, Tracey Emin, Gillian Wearing and the late Paula Rego. Runs until 20th August. Admission charge applies. For more, see royalacademy.org.uk.

Send all items to exploringlondon@gmail.com

What’s in a name?…Shoe Lane…

This name of this rather long laneway, which runs from Charterhouse Street, under Holborn Viaduct, all the way south to Fleet Street, doesn’t have anything to do with footwear.

The name is actually a corruption of the Sho Well which once stood at the north end of the thoroughfare (and which itself may have been named after a tract of land known as Shoeland Farm thanks to it resembling a shoe in shape).

In the 13th century the lane was the London home of the Dominican Black Friars – after they left in the late 13th century, the property became the London home of the Earl of Lincoln and later became known as Holborn Manor.

In the 17th century, the lane was known as for its signwriters and broadsheet creators as well as for a famous cockpit which was visited by none other than diarist Samuel Pepys in 1663. It was also the location of a workhouse.

Prominent buildings which have survived also include St Andrew Holborn, designed by Sir Christopher Wren (it actually survived the Great Fire of London but was in such a bad state of repair that it was rebuilt anyway). The street these days is lined with office buildings.

Famous residents have included John de Critz, Serjeant Painter to King James I and King Charles I, preacher Praise-God Barebone who gave his name to Barebone’s Parliament held in 1653 during the English Commonwealth, and Paul Lovell, who, so the story goes, refused to leave his house during the Great Fire of 1666 and so died in his residence.

8 locations for royal burials in London…1. (Old) St Paul’s Cathedral…

Following the laying to rest of Queen Elizabeth II in St George’s Chapel, Windsor, we’re taking a look at where some royal burials have taken place within London.

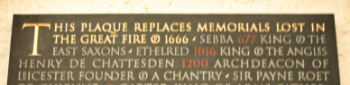

We start our new series with Old St Paul’s Cathedral which believed to have been the burial site of two Anglo-Saxon kings before it was destroyed in the Great Fire of 1666.

Aethelred (Ethelred) the Unready, who ruled from 978 until 1013 (and then again from 1014 until his death on 23rd April, 1016) was known to have been buried in the quire of the old cathedral (it’s marked on Wenceslaus Hollar’s 1658 plan of the cathedral as being on the northern side of the quire, just past the north transept) but his tomb was lost in the fire.

His memorial is among those which were lost in the Great Fire mentioned on a modern plaque in the crypt of the St Paul’s of today.

While his was the last royal burial to take place in St Paul’s, Aethelred wasn’t the only Anglo-Saxon king who was interred there.

Sæbbi, a king of the East Saxons who ruled from 664 to 694 (and is also known as Sebba or Sebbi), is also listed as being buried there (Aethelred was apparently buried close to him) and his grave also lost in the great fire.

There’s a story that when Sæbbi was about to be buried in a stone coffin, it was found it was too short for his body to lie at full length. Various solutions were proposed – including burying him with bent legs, but when they put the body back in the stone coffin this time, miraculously, it did fit.

Following an earlier fire in St Paul’s – in 1087 – Sæbbi body was transferred to a black marble sarcophagus in the mid-1100s and it’s that which was lost in the Great Fire.

10 (lesser known) statues of English monarchs in London…7. Three Stuart Kings and a Queen…

The equestrian statue of King Charles I at the top of Whitehall is one of London’s most well-known. But less well-known is the statue of the ill-fated King which can be found standing in a niche on the Temple Bar gateway, located at the entrance to Paternoster Square just outside of St Paul’s Cathedral.

Charles is not alone. Part of the gateway’s purpose was as a dynastic statement in support of the Stuarts so the grand portal also features statues of Charles’ father King James I, his mother Queen Anne of Denmark, and his son King Charles II. King James and Queen Anne can be found on the north side of the gateway (originally the east side) and the two Charles’ on the south side (originally the west side).

The design of the gateway, which originally stood at the intersection of Fleet Street and the Strand as a ceremonial entrance into the City of London, is believed to be the work of Sir Christopher Wren who was acting on the orders of King Charles II after the Great Fire of London.

The statues, which cost a third of the total £1,500 spent on the gateway, are said to have been sculpted by one John Bushnell. They are depicted in Roman attire rather than the dress they would have worn during the period.

They were removed when the gateway was dismantled in 1878 and stored in a yard of Farringdon Road and when the gateway was re-erected at Lady Meux’s Hertfordshire estate at Theobold’s Park, they were placed back in their original locations. And they also accompanied the gateway back to the city when it was positioned its current location in 2004.

Treasures of London – Wren’s Great Model of St Paul’s Cathedral…

Housed now in the building it depicts, the Great Model of St Paul’s Cathedral was created by architect Sir Christopher Wren to show King Charles II what his proposed grand new English Baroque cathedral would look like (following the destruction of the medieval cathedral in the Great Fire of 1666).

Made of oak, plaster and lime wood, the model was made by William Cleere to Wren’s design in between September, 1673, and October, 1674, at a scale of 1:25. It measures 6.27 metres long, 3.68 metres wide and more than four metres tall, making it one of the largest in the UK.

The model, which cost about £600 to make – an extraordinary sum which could apparently buy a good London house, was designed to be “walked through” at eye level and, as well as being a useful way to show the King what the proposed building would look like, was also something of an insurance policy in case something happened to Wren.

It was based on drawings made by Wren and his assistant Edward Woodroofe on a large table in the cathedral’s convocation or chapter house (later demolished in the early 1690s) and was originally painted white to represent Portland stone with a blue-grey dome and gilded details.

There are some differences between the model and the finished cathedral – among them was a substantial extension of the quire, double-height portico on the west front, and, of course, the bell towers on the west front which were made in place of the cupola which was located halfway down the nave on the model.

Part of an earlier wooden model from 1671 also survives – it was apparently lost for many years and rediscovered in 1935.

The Great Model can be seen on tours of the Triforium.

WHERE: St Paul’s Cathedral (nearest Tube stations are St Paul’s, Mansion House and Blackfriars); WHEN: 8.30am to 4.30pm Monday to Saturday; COST: £21 adults/£18.50 concessions/£9 children/£36 family (these are walk-up rates – online advanced and group rates are discounted); WEBSITE: www.stpauls.co.uk (for tours, head to www.stpauls.co.uk/visits/visits/guided-tours)

10 historic stairways in London – 3. The Monument stairs…

Running up the centre of the tallest free-standing stone column in the world, this 311 step stairway takes the visitor straight to the top of the Monument erected to commemorate the Great Fire of 1666.

The Monument – actually a Doric column – was built close to Pudding Lane in the City – where the fire is believed to have started – between 1671 and 1677. It was designed by Sir Christopher Wren in collaboration with City Surveyor Sir Robert Hooke.

The cantilevered stairway – each step of which measures exactly six inches high – leads up to a viewing platform which provides panoramic views of the City. Above the platform stands is a large sculpture featuring a stone drum topped with a gilt copper urn from which flames emerge as a symbol of the fire (King Charles II apparently squashed the idea of an equestrian statue of himself lest people think he was responsible for the fire).

Interestingly, the circular space in the centre of the stairway was designed for use as a zenith telescope (a telescope which points straight up). There is a small hatch right at the top which can be opened up to reveal the sky beyond and a subterranean lab below (reached through a hatch in the floor of the ticket both) where it was envisaged the scientist could take measurements using a special eyepiece (two lenses would be set into the actual telescope). But it wasn’t successful (reasons for this could have been vibrations caused by passing traffic or the movement of the column in the wind).

Hooke also apparently attempted to use the staircase drop for some other experiences – including measuring differences in air pressure.

Among those who have climbed the stairs was writer James Boswell who visited the Monument and climbed the stairs in 1763. He suffered a panic attack halfway up but was able to complete the climb.

WHERE: The Monument, junction of Fish Street Hill and Monument Street (nearest Tube station is Monument); WHEN: Check website; COST: £5.40 adults/£2.70 children (aged five to 15)/£4.10 seniors (joint tickets with Tower Bridge available); WEBSITE: www.themonument.org.uk

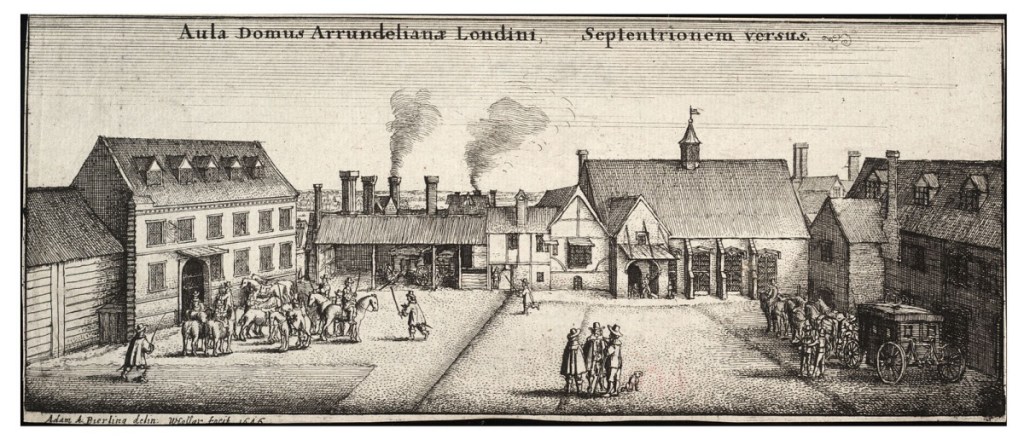

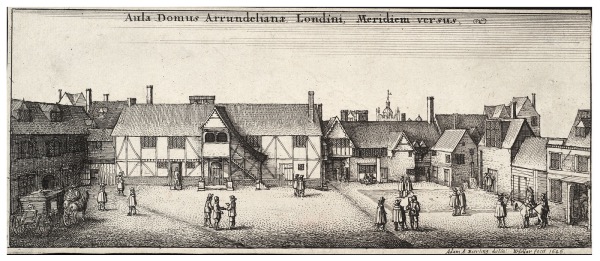

Lost London – Arundel House…

One of a string of massive residences built along the Strand during the Middle Ages, Arundel House was previously the London townhouse of the Bishops of Bath and Wells (it was then known as ‘Bath Inn’ and Cardinal Thomas Wolsey was among those who resided here during this period).

Following the Dissolution, in 1539 King Henry VIII granted the property to William Fitzwilliam, Earl of Southampton (it was then known as Hampton Place). After reverting to the Crown on his death on 1542, it was subsequently given to Thomas Seymour, 1st Baron Seymour of Sudeley, a younger brother of Queen Jane Seymour, Henry VIII’s third wife, and known as ‘Seymour Place’. Then Princess Elizabeth (late Queen Elizabeth I) stayed at the property during this period (in fact, it’s said her alleged affair with Thomas Seymour took place here).

Seymour significantly remodelled the property, before in 1549, he was executed for treason. The house was subsequently sold to Henry Fitz Alan, 12th Earl of Arundel, for slightly more than £40. He was succeeded by his grandson, Philip Howard, but he was tried for treason and died in the Tower of London in 1595. In 1603, the house was granted to Charles, Earl of Nottingham, but his possession was short-lived.

Just four years later it was repurchased by the Howard family – in particular Philip’s son, Thomas Howard, 14th Earl of Arundel – who had been restored to the earldom.

Howard, who was also the 4th Earl of Surrey, housed his famous collection of sculptures, known as the ‘Arundel Marbles’, here (much of his collection, described as England’s first great art collection, is now in Oxford’s Ashmolean Museum).

During this period, guests included Inigo Jones (who designed a number of updates to the property) and artist Wenceslas Hollar who resided in an apartment (in fact, it’s believed he drew his famous view of London, published in 1647, while on the roof).

Howard, known as the “Collector Earl”, died in Italy in 1646. Following his death, the property was used as a garrison and later, during the Commonwealth, used as a place to receive important guests

It was restored to Thomas’ grandson, Henry Howard, 6th Duke of Norfolk, following the Restoration. Following the Great Fire of London in 1666, for several years the property was used as the location for Royal Society meetings.

The house was demolished in the 1678. It’s commemorated today by the streets named Surrey, Howard, Norfolk and Arundel (and a late 19th century property on the corner of Arundel Street and Temple Place now bears its name).

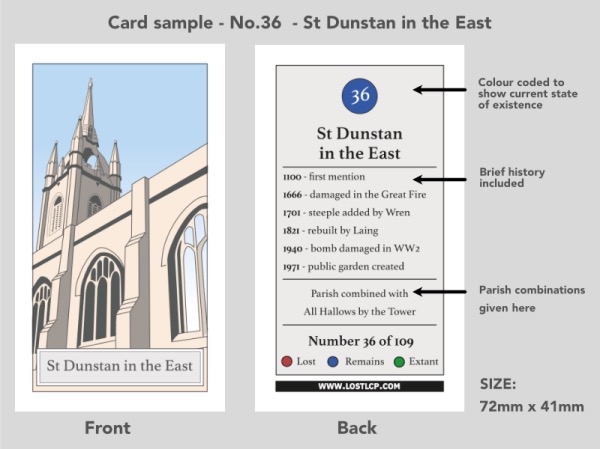

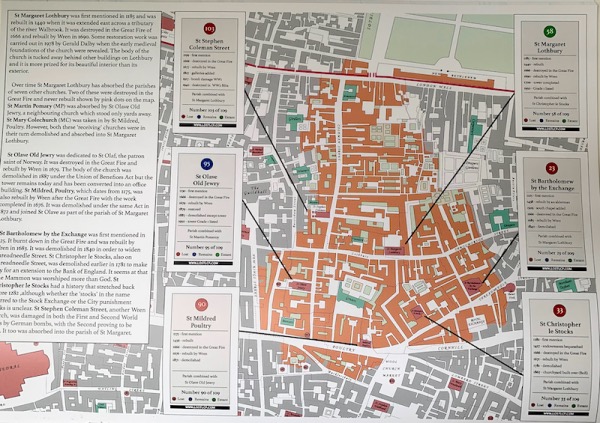

10 Questions – John Brodie Donald, Lost London Churches Project…

John Brodie Donald, the creator of the Lost London Churches Project, talks about how the project came about, its aim and his personal favourite “lost” church…

1. First up, when you talk about London’s “lost churches”, what do you mean by the expression?

“Of the 108 churches in the City of London in 1600 only 39 remain. The rest have been lost in the last 350 years, either destroyed in the Great Fire of London in 1666 or in the Blitz or demolished by commercial developers as property prices soared.”

2. What is the aim of the Lost London Churches Project?

“The Lost London Churches Project aims to promote interest in the ancient church buildings and parishes of the City of London through collectable cards, books, maps and downloadable explorers walks. We have created a ecclesiastical treasure hunt – a way of exploring the history of the square mile that costs nothing and can be easily fitted into a few spare lunchtimes.”

3. How many churches are included in the project?

“There are 78 churches for which collectable cards have been produced and these are available in a growing number of churches in the City. It is hard to find evidence of what the churches lost in the fire of 1666 looked like, but hopefully after further research these will be included in a second edition. “

4. Does the project cover every “lost” church in the City of London?

“It covers not just ‘lost’ churches but also the extant ones for two reasons. First, because those who are collecting the cards need a place to pick them up which they can do in the churches that still exist. Secondly, although the church buildings were lost, the parishes still remain to this day for administrative reasons. Every one of the 109 churches still has a parish clerk. The parishes have been amalgamated with the existing churches. So, for example, St Vedast in Foster Lane is a church of 13 united parishes having acquired them as the church buildings were lost over the centuries.”

5. Tell us how the Lost London Churches Project came about?

“It all started when I was redrawing the Ogilby and Morgan map of 1676 in colour for my own pleasure. This large scale map (100 feet the inch) shows every single house in the City of 350 years ago. It was completed just after the Great Fire and so shows the location of all the lost churches clearly. The original covered 20 separate black and white sheets but I redrew them all joined together in colour on my computer. The end result was so huge it was impractical to print…So it made sense to break it up and publish in a book, and since the most interesting information in the map was the churches lost in the fire. it became the basis for the collectors book for the Lost London Churches project. At the same time, I was going through my late father’s papers and found a booklet of cigarette cards that he had collected in the 1940s. He also had a passion for painting watercolours of churches. That’s when I had the idea of producing a series of ‘cigarette cards’ showing the lost churches and the project was born.”

6. What’s the role of the cards?

“The role of the cards is to give some tangible treasure to collect while exploring the lost churches. Like trading cards or Pokemon the challenge is – can you collect them all? In every participating church you will be able to pick up that church’s card along with a pack of five random cards for a small voluntary donation. Cards are also available from the project’s website lostlcp.com.”

7. You mentioned earlier that there were a number of ways the City of London’s churches become lost?

“They were lost in three phases. Around 85 were destroyed or damaged in the Great Fire of 1666 of which 34 were never rebuilt. The others were rebuild by Christopher Wren, along with St Pauls Cathedral. Then 26 more churches were lost after the Union of Benefices Act of 1860 triggered a second wave of demolition. The purpose of the act was to combine parishes and free up space for the swelling capital of the British Empire. Lastly, the City suffered badly in the Blitz of World War II which took a further toll on these ancient buildings.”

8. How easy is it to spot remnants of the City’s lost churches?

“Though the buildings are lost, the parishes remain and you can still see the old parish boundary markers even on modern buildings. The best place to see an example of these is to walk down Cheapside along the New Change shopping centre towards the church of Mary le Bow. In only 100 or so yards you will have crossed the boundaries of five different parishes; St Vedast Foster Lane, St Matthew Friday Street, St Peter Westcheap, All Hallows Bread Street and St Mary Magdalene Milk Street. As you walk down the street look up above the shops ( see picture below) and you will see little plaques marking these parish boundaries. These type of parish boundary markers are scattered throughout the City. Our downloadable explorers walks on Google Maps available (for free) on our website lostlcp.com will show you some routes to find them. There is also a A4 sized map of the ancient parishes we have published for you to use as a guide.”

9. Have you uncovered any particularly interesting stories in your research into London’s lost churches?

“I think one the most interesting things is the unusual names and how they were derived: Benet Fink, Stephen Coleman, Mary Somerset, Martin Ludgate and Gabriel Fenchurch. Couldn’t these be the names in an Agatha Christie mystery where the key to the murder is church themed aliases? But seriously, every church has a rich history since most were established before 1200 so in visiting them you are trekking right back to medieval times.”

10. And lastly, do you have a favourite “lost” London church?

“My favourite is St Mary Abchurch just off Cannon Street. It is not only the headquarters of the ‘Friends of the City Churches’ charity but also a perfect jewel of a Wren church with the most glorious painted ceiling – like a secret Sistine chapel!”

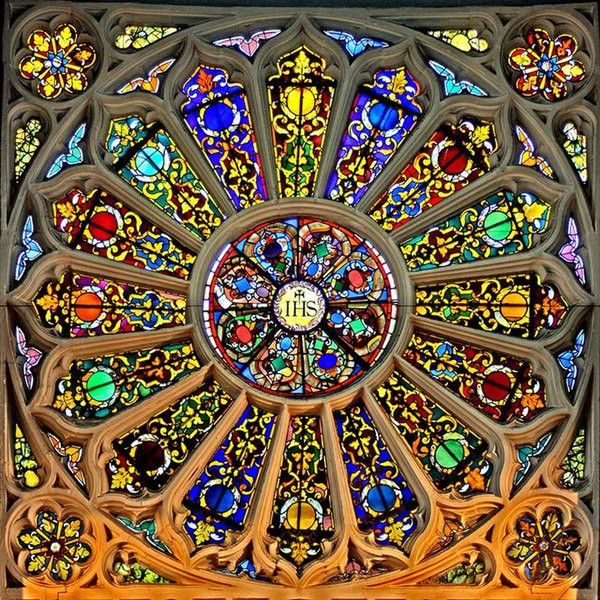

Treasures of London – The St Katharine Cree rose window…

Said to have been modelled on a rose window once inside Old St Paul’s Cathedral (which was destroyed in the Great Fire of London), the window, also known as Catherine (Katharine) Wheel, features some beautiful examples of 17th century stained glass.

The window, which is located in the chancel of the church of St Katharine Cree in Leadenhall Street in the City not far from Leadenhall Market, was installed when the church was rebuilt in the early 1630s (replacing an earlier medieval church – the church’s tower, however, dates from 1504 and was part of the earlier church on the site). It is abstract in design but

The window, which was removed to ensure its protection during World War II, has undergone repairs and the centre of the wheel was replaced after it was blown out in 1992 when a massive truck bomb went off at the nearby Baltic Exchange.

The Catherine Wheel, incidentally, was an execution device associated with the martyrdom of St Catherine of Alexandria. Catherine had upset the Emperor Maxentius in the early 4th century by speaking out against his persecution of Christians in the early fourth century. Tradition has it that after failing to break her spirit through torture (and, so say some, a marriage proposal which she refused), Maxentius ordered her to be put to death on a spiked wheel, it broke at her touch and she was later beheaded.

Where’s London’s oldest…livery company?

There are 110 livery companies in London, representing various “ancient” and modern trades. But the oldest is said to be the Worshipful Company of Weavers.

What was then known as the Weavers’ Guild was granted a charter by King Henry II in 1155 (although the organisation has an even older origins – there is an entry in the Pipe Rolls as far back as 1130 recording a payment of £16 made on the weaver’s behalf to the Exchequer).

In 1490, the Weaver’s Guild obtained a Grant of Arms, in the early 16th century it claimed the status of an incorporated craft, and, in 1577 it obtained ratification of its ordinances from the City of London.

By the late 16th century, the company – its numbers swollen by foreign weavers including Protestants fleeing persecution in Europe – built a hall on land it owned in Basinghall Street. A casualty of the Great Fire of London, the hall was rebuilt by 1669 but by the mid-1850s had fallen into disrepair and was pulled down and replaced by an office block.

After the office building was destroyed during World War II (fortunately some of the company’s treasures which had been stored there had already been moved), the company considered rebuilding the hall but decided its money could be better used, including on charitable works.

For many years, the company’s business was run from various clerk’s offices outside the City of London but since 1994 it has been run from Saddlers’ House.

The company, which ranks 42nd in the order of precedence for livery companies, has the motto ‘Weave Truth With Trust’.

For more, see www.weavers.org.uk.

10 London buildings that were relocated…6. The spire of St Antholin…

Of medieval origins,the Church of St Antholin, which stood on the corner of Sise Lane and Budge Row, had been a fixture in the City of London for hundreds of years before it was destroyed in the Great Fire of 1666.

Rebuilt to the designs of Sir Christopher Wren, it survived until 1874 when it was finally demolished to make way for Queen Victoria Street.

But, while the building itself was destroyed (and we’ll take a more in-depth look at its history in an upcoming article), a section of Wren’s church does still survive – the upper part of his octagonal spire (apparently the only one he had built of stone).

This was replaced at some stage in the 19th century – it has been suggested this took place in 1829 after the spire was damaged by lightning although other dates prior to the church’s demolition have also been named as possibilities.

Whenever its removal took place, the spire was subsequently sold to one of the churchwardens, an innovative printing works proprietor named Robert Harrild, for just £5. He had it re-erected on his property, Round Hill House, in Sydenham.

Now Grade II-listed, the spire, features a distinctive weathervane (variously described as a wolf’s head or a dragon’s head). Mounted on a brick plinth, it still stands at the location, now part of a more modern housing estate, just off Round Hill in Sydenham.