Located in at the junction of Mark Lane and Dunster Court in the City of London, All Hallows Staining was a medieval church which was mostly demolished in the late 19th century.

These days only the lonely tower remains (above ground at least) as testament to building that once stood there and the lives that were impacted by it.

All Hallows Staining was originally built in the late 12th century and while the origins of its name are somewhat shrouded in mystery, there are a couple of theories.

One says it takes its name from the fact it was built in stone when other churches at the time were wooden (“staining” meaning “stone”) while another says it takes it names from the fact it was built on land belonging to the Manor of Staines.

Princess Elizabeth (later Elizabeth I) is said to have presented the church with new bell ropes after she was released after two months in the Tower of London in 1554 during the reign of her half-sister Queen Mary I (paying tribute to the sound they provided while she was in the Tower).

The church survived the Great Fire of London in 1666 but collapsed just five years later, its foundations apparently weakened by too many graves in the adjoining churchyard.

It was rebuilt in 1674-75 but largely demolished in 1870 when the parish was combined with St Olave Hart Street (and the proceeds were used to fund construction of All Hallows, Bow, in the East End).

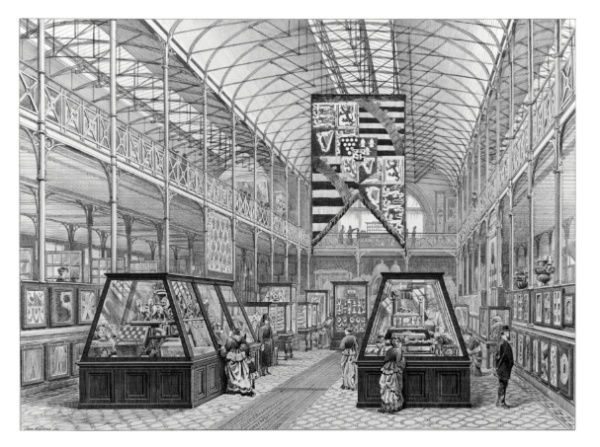

Just the tower, parts of which date from the 12th century, remained. The property was bought by the Worshipful Company of Clothworkers. Underneath the adjacent yard they installed the remains of the 12th century crypt of the hermitage chapel of St James in the Wall (later known as Lambe’s Chapel) following the demolition of the chapel in the 1870s.

During World War II, when St Olave Hart Street was badly damaged in the Blitz, a temporary prefabricated church was erected on the site of All Hallows Staining which used the tower as its chancel. It was known as St Olave Mark Lane.

The church was Grade I listed in 1950. In 1957, Clothworkers had a hall for St Olave Hart Street constructed on part of the site of the former church.

The tower is usually able to be seen across a small yard from Mark Lane.