Now long gone, this central London property was once the residence of the, you guessed it, bishops of Durham.

Medieval

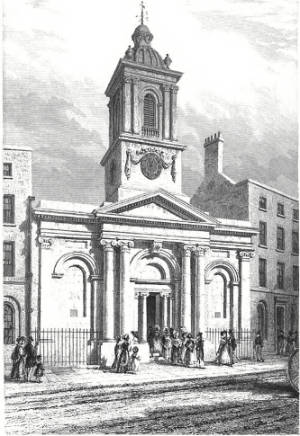

Lost London – Church of St Peter le Poer…

This parish church once stood on the west side of Broad Street in the City of London and dated back to the Norman era.

The church, which originally dated from before 1181 (when it was first mentioned) and was also referred to as St Peter le Poor, may have been so-named because of the poor parish in which it was located or for its connections to the monastery of St Augustine at Austin Friars, whose monks took vows of poverty.

Whatever the reason for its name (and it has been suggested the ‘le Poer’ wasn’t added to it until the 16th century), the church was rebuilt in 1540 and then enlarged in 1615 with a new steeple and west gallery added in the following decade or so.

The church survived the Great Fire of London in 1666 but just over a 100 years later has fallen into such a state of disrepair that parishioners obtained an Act of Parliament to demolish and rebuild it.

The new church, which was designed by Jesse Gibson and moved back off Broad Street further into the churchyard, was consecrated on 19th November, 1792. Its design featured a circular nave topped by a lantern (the curved design was not visible from the street) and placed the altar directly opposite the doorway on the north-west side of the church.

The church had acquired a new organ in 1884 but the declining population in the surrounding area led to its been deemed surplus to requirements. It was demolished in 1907 and the parish united with that of St Michael Cornhill.

Proceeds of the sale were used to build a new church, St Peter Le Poer in Friern Barnet. The new church, which was consecrated on 28th June, 1910, by the Bishop of London, the Rt Rev Arthur Foley Winnington-Ingram, also received the demolished church’s font, pulpit and panelling.

10 London bishop’s palaces, past and present – 2. York Place…

The precursor to Whitehall Palace, York Place was the London residence of the Archbishops of York between the 13th and 16th centuries.

Subscribe for just £3 a month to access all of Exploring London’s content…

What’s in a name?…Upminster…

Known to many as the eastern end of the District Line, Upminster is located some 16.5 miles to the north-east of Charing Cross and is part of the London Borough of Havering.

Historically a rural village in the county of Essex, its name comes from Old English and means a large church or “minster” located on high ground.

The church is said to have dated at least as far back as the 7th century and to have been one of a number founded by St Cedd, a missionary monk of Lindisfarne, in the area. It was located on the site occupied by the current church of St Laurence (parts of which date back to the 1200).

The nearby bridge over the River Ingrebourne shares the name Upminister and is known to have been in existence since the early 14th century.

Once wooded, the area was taken over for farming (cultivation dates as far back as Roman times) and by the 19th century it came to be known for market gardens as well as for some industry including windmills and a brickworks.

Development was initially centred around the minister and nearby villages of Hacton and Corbets Tey. It received a boost in the 17th century when wealthy London merchants purchased estates in the area.

Improved transportation links also helped in later centuries including the arrival of the London, Tilbury and Southend Railway in 1885 – it was extended from Barking – and the underground in 1902 via the Whitechapel and Bow Railway.

Landmarks include the Church of St Laurence, the redbrick Clock House (dating from about 1775), the 16th century house Great Tomkyns, the Grade II*-listed Upminster Windmill, built in 1803 and considered one of England’s best surviving smock mills, and the 15th century tithe barn (once owned by the monks of Waltham Abbey and now a museum).

Upminster Hall, which dates back to the 15th and 16th century (and, once the hunting seat of the abbots of Waltham Abbey, was gifted by King Henry VIII to Thomas Cromwell after the Dissolution), is now the clubhouse of the Upminister Golf Club.

Hornchurch Stadium, the home ground of AFC Hornchurch, is located in the west of the area.

It was in Upminster that local rector Rev William Derham first accurately calculated the speed of sound, employing a telescope from the tower of the Church of St Laurence to observe the flash of a distant shotgun as it was fired and then measuring the time before he heard the gunshot using a half second pendulum.

What’s in a name?….Giltspur Street

This City of London street runs north-south from the junction of Newgate Street, Holborn Viaduct and Old Bailey to West Smithfield. Its name comes from those who once travelled along it.

An alternative name for the street during earlier ages was Knightrider Street which kind of gives the game away – yes, the name comes from the armoured knights who would ride along the street in their way to compete in tournaments held at Smithfield. It’s suggested that gilt spurs may have later been made here to capitalise on the passing trade.

The street is said to have been the location where King Richard II met with the leaders of the Peasant’s Revolt who had camped at Smithfield. And where, when the meeting deteriorated, the then-Lord Mayor of London William Walworth, ending up stabbing the peasant leader Wat Tyler who he later captured and had beheaded.

St Bartholomew’s Hospital can be found on the east side of the street. On the west side, at the junction with Cock Lane is located Pye Corner with its famous statue of a golden boy (said to be the place where the Great Fire of London was finally stopped).

There’s also a former watch house on the west side which features a monument to the essayist late 18th century and 19th century Charles Lamb – the monument says he attended a Bluecoat school here for seven years. The church of St Sepulchre-without-Newgate stands at the southern end with the Viaduct Tavern on the opposite side of the road.

The street did formerly give its name to the small prison known as the Giltspur Street Compter which stood here from 1791 to 1853. A prison for debtors, it stood at the street’s south end (the location is now marked with a City of London blue plaque).

Treasures of London – The Medieval Palace at the Tower of London…

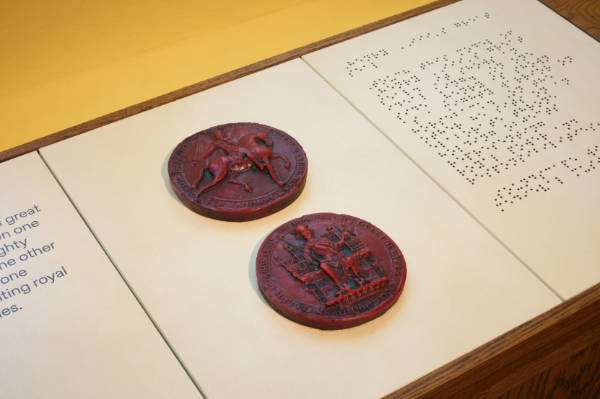

Located in one of the oldest parts of the city’s iconic fortress, the medieval palace has undergone a revamp with a restoration of the sumptuous and extravagant decorative scheme that was in place in the 13th century.

The medieval palace is found within the St Thomas’s Tower, the Wakefield Tower and the Lanthorn Tower on the southern side of the Tower and was built on the orders of successive monarchs, King Henry III and his son King Edward I. They were used as a domestic and diplomatic space periodically by the kings and their queens, Eleanor of Provence and Eleanor of Castile.

The medieval palace today includes a recreation of Edward I’s vibrant bedchamber in the St Thomas’s Tower (which once directly fronted the River Thames and sits above the water gate later known as Traitor’s Gate) and an exploration of the influence Eleanor of Castile had on the decoration.

The Wakefield Tower, meanwhile, was built by King Henry III as royal lodgings between 1220 and 1240. It originally sat at the river’s edge and could be accessed from the river by private stairs.

Believed to have been used as an audience chamber, it contains a recreation of a throne and canopy based on 13th century examples which are decorated with a Plantagenet lion – the symbol of the royal family. The vaulted ceiling is 19th century.

The third of the towers – the Lanthorn Tower – was built as lodgings for King Henry III’s Queen but is now a 19th century reconstruction after the original tower was gutted by fire.

It contains a display and among the new objects is a stone, on loan from the Jewish Museum London, which came from a Jewish mikveh or ritual bath, dating to about 1200 and discovered in London in 2001 within the home of the medieval Crespin family. It’s part of a new effort to explore the story of London’s medieval Jewish community, the taxation of which helped to pay for the construction of St Thomas’s Tower in the 1270s.

Other new objects on show in the Lanthorn Tower include a 13th century seal matrix from a 13th century Italian knight and a gold and enamel 13th century pyx – a small round container used to hold communion wafers made in the French city of Limoges (both on loan from the British Museum) as well as a child’s toy knight made of lead that dates from c1300, lent by London Museum and a perfectly preserved wicker fish trap which was excavated from the Tower moat, containing bones likely dating from the 15th or 16th century and illustrating the moat’s role as a fishery.

The medieval palace also includes a small private chapel which is where it’s believed King Henry VI died in 1471.

Among other stories now told in the display is that of less well-known Tower residents such as King Edward I’s laundress Matilda de Wautham, and John de Navesby the keeper of the white bear which was held in the menagerie at the Tower.

WHERE: The Medieval Palace, The Tower of London (nearest Tube Station is Tower Hill); WHEN: 9am to 5:30pm daily (last entry 3:30pm); COST: £35.80 adults; £28.50 concession; £17.90 children (free for Historic Royal Palaces members and £1 tickets are available for those in receipt of certain means-tested financial benefits); WEBSITE: www.hrp.org.uk/tower-of-london/

10 historic London docks…8. St Saviour’s Dock…

Located in an inlet where the River Neckinger enters the Thames just to the east of Tower Bridge, this dock has been used since the early middle ages.

Subscribe for just £3 a month to see all of Exploring London’s content – and support our work.

Lost London – Gatehouse Prison…

Located in what was the gatehouse of Westminster Abbey, this small prison dates from 1370.

It was built by Walter de Warfield, then the abbey’s Cellarer, and featured two wings, built at right angles to each other.

Under the jurisdiction of the Abbot, the prison had two sections – one for clerics and one for laymen. The Abbey’s Janitor was its warder.

Among the most famous inmates was the Cavalier poet Richard Lovelace who was imprisoned for petitioning to have the Clergy Act 1640 annulled. While inside, he wrote the famous work, To Althea, from Prison which features the famous lines: “Stone walls do not a prison make, Nor iron bars a cage”.

Other notables include Sir Walter Raleigh, held here on the night before he was beheaded in Old Palace Yard on 29th October 1618, diarist Samuel Pepys – detained for a few weeks in 1689 on suspicion of being a Jacobite (but released because of ill health), and Gunpowder Plot conspirator Thomas Bates.

Falling into a state of decay, the prison was demolished in 1776-77 (although one wall stood until the 1830s). A gothic column, the Westminster Scholars’ Memorial which is also known as the Crimea and Indian Mutiny Memorial, now stands on the site.

A Moment in London’s History – The taking of the Stone of Scone…

A rectangular block of pale yellow sandstone decorated with a Latin cross, the Stone of Scone, also known as the Stone of Destiny, long featured in the crowning of Scottish kings. But in 1296, it was seized by King Edward I as a trophy of war.

He brought it back to England (or did he? – it has been suggested the stone captured by Edward was a substitute and the real one was buried or otherwise hidden). In London, it was placed under a wooden chair known as the Coronation Chair or King Edward’s Chair on which most English and later British sovereigns were crowned.

On Christmas Day, 1950, four Scottish nationalist students – Ian Hamilton, Kay Matheson, Gavin Vernon and Alan Stuart – decided to liberate the 152 kilogram stone and return it to Scotland.

The stone broke in two when it was dropped while it was being removed (it was later repaired by a stone mason). The group headed north and, after burying the greater part of it briefly in a field to hide it, the stone was – on 11th April, 1951 – eventually left on the altar of Arbroath Abbey in Scotland.

No charges were ever laid against the students.

It was brought back to the abbey and used in the coronation of Queen Elizabeth II in 1953.

The stone was eventually returned to Scotland in 1996 on the proviso it could be temporarily relocated back to London for coronations and now sits in Edinburgh Castle. It was taken to London temporarily in 2023 for the coronation of King Charles III but has since been returned.

There is a replica of the stone at Scone Castle in Scotland.

10 London mysteries – 6. The disappearance of Edward V and his brother Richard…

The disappearance of King Edward V and his brother, Richard, Duke of York, after being last seen in the Tower of London is one of London’s most famous mysteries. And while it’s one we’ve written about before, we thought we’d take a look at the recent announcement that new evidence had been found in the matter.

Subscribe to Exploring London for just £3 a month to access all of our articles…

10 London mysteries – 4. How did King Henry VI die?

The Tower of London is known for many mysteries – the most famous, perhaps, being the fate of the two ‘Princes in the Tower’. But among the other mysterious deaths which took place behind the closed doors of the fortress is the death of the deposed King Henry VI.

Support our work for just £3 a month to gain access to all Exploring London’s content!

This Week in London – Lord Mayor’s Show; ‘Poppy Fields at the Tower’; and, ‘The Great Mughals’ at the V&A…

• The Lord Mayor’s Show – featuring the 696th Lord Mayor of London, Alastair King – will be held this Saturday. The three-mile long procession – in which the Lord Mayor will ride in the Gold State Coach – features some 7,000 people, 250 horses, and 150 floats. It will set off from Mansion House at 11am and travel down Poultry and Cheapside to St Paul’s Cathedral before moving on down Ludgate Hill and Fleet Street to the Royal Courts of Justice. The return journey will set off again at 1:10pm from Temple Place and travel via Queen Victoria Street back to Mansion House where he will take the salute from the Pikemen and Musketeers at 2:40pm. For more information, including where to watch the show, head to https://lordmayorsshow.london.

• An immersive sound and light show commemorating World War I and II opens at the Tower of London tomorrow ahead of Armistice Day and Remembrance Sunday. Historic Royal Palaces has partnered with Luxmuralis to present Poppy Fields at the Tower with visitors invited to go inside the Tower where – recalling the 2014 display Bloodswept Lands and Seas of Red in the Tower of London moat to mark the centenary of World War I – the walls will not only be illuminated with tumbling poppies but also historic photographs, documents and plans. The display is being accompanied by music composed by David Harper, and poetry recordings. Visitors will also be granted special access to see the Crown Jewels after-hours to learn more about their removal from the Tower during both World Wars. Runs until 16th November and should be pre-booked. Admission charges apply. For more, see https://www.hrp.org.uk/tower-of-london/whats-on/poppy-fields-at-the-tower/.

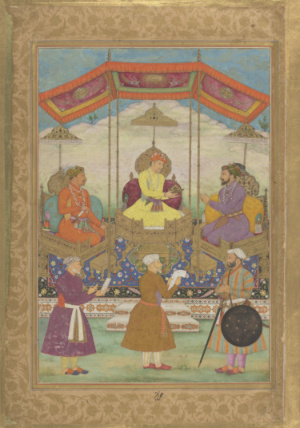

from the Minto Album. © CC BY – 4.0. Chester Beatty, Dublin

• An exhibition celebrating the golden age of the Mughal Court opens at the V&A in South Kensington on Saturday. The Great Mughals: Art, Architecture and Opulence examines the “creative output and internationalist culture” of Mughal Hindustan during the age of its greatest emperors, a period spanning c1560 to 1660. More than 200 objects are on display arranged in three sections corresponding to the reigns of the Emperor Akbar (1556-1605), Jahangir (1605 to 1627) and Shah Jahan (1628 to 1658). The objects include paintings, illustrated manuscripts, vessels made from mother of pearl, rock crystal, jade and precious metals. Highlights include four folios from the Book of Hamza, commissioned by Akbar in 1570, and the Ames carpet which was made in the imperial workshops between c1590 and 1600 and is on display for the first time in the UK. There’s also a unique wine cup made from white nephrite jade in the shape of a ram’s head for Shah Jahan in 1657, two paintings depicting a North American Turkey Cock and an African zebra created by Jahangir’s artists, and a gold dagger and scabbard set with over 2,000 rubies, emeralds and diamonds. Runs in Galleries 38 and 39 until 5th May. Admission charge applies. For more, see www.vam.ac.uk.

• Send all items for inclusion to exploringlondon@gmail.com.

10 towers with a history in London – 10. The ‘Lollard’s Tower’, Lambeth Palace…

This 15th century tower can be found at the north-west corner of Lambeth Palace, London residence of the Archbishop of Canterbury.

Subscribe for just £3 a month to gain access to all our stories – that’s less than the price of a cup of coffee!

10 towers with a history in London – 7. Tower of the former Church of St Mary-at-Lambeth…

Part of the deconsecrated Church of St Mary-at-Lambeth – now the home of the Garden Museum, is a tower which was first built in the 14th century.

Support our work and subscribe for just £3 a month to see all of Exploring London’s content

10 towers with a history in London – 2. The tower of St Olave, Old Jewry…

This tower is a survivor and was originally part of the rebuilt Church of St Olave, Old Jewry.

The medieval church, which was apparently built on the site of an earlier Saxon church, originally dated from 12th century. Its name referred to both the saint to whom it was dedicated – the patron saint of Norway, St Olaf (Olave) – and its location in the precinct of the City that was largely occupied by Jews (up until the infamous expulsion of 1290).

The church, which is also referred to as Upwell Old Jewry (this may have related to a well in the churchyard), was the burial place of two former Lord Mayors – mercer Robert Large (William Caxton was his apprentice) and publisher John Boydell (who apparently washed his face under the church pump each morning). Boydell’s monument was later transferred to St Margaret Lothbury.

The church was sadly destroyed in the Great Fire of 1666 but it was among those rebuilt under the eye of Sir Christopher Wren in the 1670s. It’s from this rebuilding that the current tower dates.

At this time, the parish was united with that of St Martin Pomeroy (which had already shared its churchyard and which was also destroyed in the Great Fire).

Wren’s church was eventually demolished in 1887 as moves took place to consolidate church parishes under the Union of Benefices Act – the parish was united with that of St Margaret Lothbury and proceeds from the sale were used to fund the building of St Olave, Monor House. It’s worth noting that a Roman pavement was found on the site after the church demolition.

The tower (and the west wall), meanwhile, survived. The tower was subsequently turned into a rectory for St Margaret Lothbury and later into offices.

Interestingly, the Grade I-listed, Portland stone tower is said to be the only one built by Wren’s office which is battered – that is, wider at the bottom than the top. It’s topped by some obelisk-shaped pinnacles and a weather vane in the shape of a sailing ship which was taken from St Mildred, Poultry (was demolished in 1872).

The tower’s former clock was built by Moore & Son of Clerkenwell. It was removed at the time of the church demolition was installed in the tower of St Olave’s Hart Street. The current clock was installed in 1972.

Lost London – The Guildhall Chapel…

Used by the Lord Mayor of London and his retinue as a location for weekly worship for more than 200 years, the Guildhall Chapel was once an important part of the City infrastructure.

Please consider supporting our work for just £3 a month.

10 towers with a history in London – 1. The Bloody Tower…

Carrying rather a gruesome name, this rectangular-shaped tower sits over a gate leading from outer ward into the inner ward in the Tower of London.

The tower, which once controlled the watergate before the outer walls were constructed, was originally known as the Garden Tower due to its location adjoining the Tower Lieutenant’s Garden.

To see the rest of this post (and all of our coverage), subscribe for just £3 a month. This small contribution – less than the cost of a cup of coffee – will help us continue and grow our coverage. We appreciate your support!

(More) atmospheric ruins in London…

Further to our recent series on atmospheric ruins in London, here are eight more ruins we’ve previously mentioned that deserve a place on the list:

Lost London – St Dunstan in the East…

Lost London – Winchester Palace

10 subterranean sites in London – 5. Whitefriars Priory crypt…

Lost London – Billingsgate Roman House and Baths

10 atmospheric ruins in London – 9. Barking Abbey…

Once one of the most important nunneries in the country, Barking Abbey was originally established in the 7th century and existed for almost 900 years before its closure in 1539 during King Henry VIII’s Dissolution.

The abbey was founded by St Erkenwald (the Bishop of London between 675 and 693) for his sister St Ethelburga who was the first abbess.

In the late 900s, St Dunstan, the Archbishop of Canterbury introduced the Rule of St Benedict at the nunnery.

King William the Conqueror stayed here after his coronation while famous abbesses included Mary Becket, the sister of St Thomas Becket, Archbishop of Canterbury, who was given the title in 1173 in reparation for the murder of her brother, as well as several royals including Queen Maud, wife of King Henry I, and Matilda, wife of King Stephen.

The nunnery gained wealth and prestige but this suffered somewhat as a result of floods in 1377 with some 720 acres of land permanently lost. It nonetheless remained one of the wealthiest in England and it’s said the abbess had precedence over all other abbesses in the country.

After the abbey was dissolved, some of the building materials were reused elsewhere and the site was later used as a farm and quarry.

Most of the buildings were demolished – today only the Curfew Tower, which dates from around 1460, remains. The Grade II*-listed tower contains the Chapel of the Holy Rood and now serves at the gateway to the nearby St Margaret’s Church.

Building footings also remain buried under the ground in what is known today as Abbey Green (the layout is marked today by modern additions). There’s a model of how the abbey once appeared inside the gateway.

Barking Abbey ruins, Abbey Road, Barking (nearest Tube Station is Barking); WHEN: Daily: COST: Free; WEBSITE: https://www.lbbd.gov.uk/find-your-nearest/barking-abbey-ruins

10 atmospheric ruins in London – 8. Coldharbour Gate…

Located within the outer walls of the Tower of London are the remains of some early 13th century fortifications built by King Henry III.

These include the foundations of Coldharbour Gate which once adjoined the south-west corner of the White Tower as well as the western wall of the Inmost Ward which ran down to the Wakefiekd Tower.

The gate was defended by two cylindrical turrets while the Inmost Ward Wall has arrow loops installed, allowing archers to fire down on attackers who had breached the outer fortifications.

The gate was later used as a prison. Alice Tankerville, who was charged with piracy on the River Thames, became one of the most famous prisoners housed there when, despite having apparently been chained to the wall, she escaped with the help of two guards in 1533 (she was recaptured just outside the Tower).

The gateway was demolished in about 1675 and lead from the roof taken to Greenwich where it was redeployed at the Royal Observatory.

Much of the wall was hidden away behind later buildings but was re-exposed after being bomb damaged during World War II.

Not much remains to be seen today but the foundations do evoke a sense of the royal palace in times past and serve as a reminder that the buildings we see at the Tower today are not all that has existed here.

Other ruins at the Tower of London include the remains of the Wardrobe Tower, which lies at the south-east corner of the White Tower. It is thought to have dated from 1190 and incorporates the base of a Roman bastion.

WHERE: Tower of London (nearest Tube station Tower Hill); WHEN: 9am to 5.30pm (last admission 3.30pm), Tuesday to Saturday; 10am to 5.30pm (last admission 3.30pm) Sunday to Monday; COST: £34.80 adults; £17.40 children 5 to 15 (family tickets available; discounts for online purchases/memberships); WEBSITE: www.hrp.org.uk/toweroflondon/.