The next two entries in Exploring London’s 100 most popular posts countdown…

Fetter Lane

10 (more) fictional character addresses in London – 1. Fetter Lane, Old Jewry and Wapping…

Lemuel Gulliver, the ‘hero’ of Jonathan Swift’s 1726 book, Gulliver’s Travels, wasn’t a native Londoner but moved to the city for work and lived in several different locations before embarking on his famous voyage to the land of Lilliput.

According to the book, the Nottinghamshire-born Gulliver studied at Emanuel College (sic) in Cambridge before he was apprenticed to London surgeon known as James Bates after which he spent a couple of years studying in the Dutch town of Leiden (spelt Leydon in the book).

According to the book, the Nottinghamshire-born Gulliver studied at Emanuel College (sic) in Cambridge before he was apprenticed to London surgeon known as James Bates after which he spent a couple of years studying in the Dutch town of Leiden (spelt Leydon in the book).

Returning to England briefly, he spent the next few years voyaging to the “Levant” before returning to London where he “took part of a small house in Old Jewry” (Old Jewry lies in the City of London runs between Poultry and Gresham Street) and married Mary Burton, daughter of a Newgate Street hosier.

His master Bates dying, however, a couple of years later and with a failing business, he took up the position of surgeon on two different ships and it was when he eventually returned to London that he moved to Fetter Lane – which runs north from Fleet Street – and then from there to Wapping where hoping to retire from the sea and “get business (presumably he meant medical cases) among the sailors”.

But it was not to be and so, in 1699, Mr Gulliver set off on the voyage accounted in the famous book.

The name Fetter Lane, incidentally, has nothing to do with fetters (ie chains) – see our earlier post for more. And it’s also worth noting that the author, Jonathan Swift, also visited and lived in London at various times of his career – we’ll take a more in depth look at his experiences in a later post.

PICTURE: Lemuel Gulliver, depicted in a first edition of Gulliver’s Travels/Wikipedia.

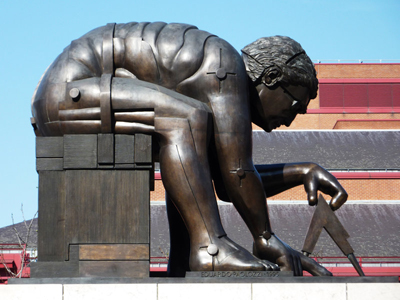

LondonLife – Isaac Newton comes to life…

Eduardo Paolozzi’s 1995 statue of Isaac Newton which stands on the British Library’s piazza in King’s Cross has been granted a ‘voice’ as part of a new project called Talking Statues. Visitors who swipe their smartphones on a nearby tag will receive a call from the famous scientist – voiced by Simon Beale Russell – as part of the initiative which is being spear-headed by Sing London. It is one of 35 different statues across London and Manchester which will be brought to life by a range of public identities. Among the other statues in London which have been brought to life are Samuel Johnson’s cat Hodge in Gough Square (voiced by Nicholas Parsons) and Dick Whittington’s Cat in Islington (Helen Lederer), John Wilkes in Fetter Lane (Jeremy Paxman), the Unknown Soldier at Paddington Station (Patrick Stewart) and Sherlock Holmes outside Baker Street Underground (Anthony Horowitz). The British Library and Sing London are also holding a competition to give William Shakespeare a voice by writing a monologue for the statue in the library’s entrance hall which will then be read by an as yet unannounced actor. Entries close 17th October. For more, visit www.talkingstatues.co.uk.

PICTURE: British Library

What’s in a name?…Fetter Lane…

The name of this central London thoroughfare – which runs from Fleet Street to a dead-end just shy of Holborn, with New Fetter Lane forking off to continue the journey to Holborn Circus – has nothing to do with fetters, chains or prisoners.

Rather its name – a form of which apparently first starts to appear in the 14th century – is believed to be a derivation of one of a number of possible Anglo-French words – though which one is anyone’s guess.

Rather its name – a form of which apparently first starts to appear in the 14th century – is believed to be a derivation of one of a number of possible Anglo-French words – though which one is anyone’s guess.

The options include the word fewtor, which apparently means an idle person or a loafer, faitor, a word which means an imposter or deceiver (both it and fewtor may refer to a colony of beggars that lived here) feuterer, a word which describes a ‘keeper of dogs’, or even feutrier, another term for felt-makers.

Buildings of note in Fetter Lane include the former Public Records Office (now the Maughan Library, part of King’s College, it has a front on Chancery Lane but backs onto the lane), and the former Inns of Chancery, Clifford’s Inn and Barnard’s Inn (current home of Gresham College).

It was also in Fetter Lane, at number 33, that the Moravians, a Protestant denomination of Christianity, established the Fetter Lane Society in 1738 (members included John Wesley). The original chapel was destroyed in bombing in World War II ( a plaque now marks the building where it was)

And there’s a statue of MP, journalist and former Lord Mayor, John Wilkes, at the intersection with New Fetter Lane (pictured).

Celebrating Charles Dickens – 9. Dickens’ literary connections, part 2…

In which we continue our look at some of London’s connections with Dickens’ writings…

• ‘Oliver Twist’ workhouse, Cleveland Street. The building, recently heritage listed following a campaign to save it, is said to have served as the model for the workhouse in Oliver Twist and was apparently the only building of its kind still in operation when Dickens wrote the book in the 1830s. Dickens had lived as a teenager nearby in a house in Cleveland Street and was living less than a mile away in Doughty Street (now the Charles Dickens Museum) when he wrote Oliver Twist. Thanks to Ruth Richardson – author of Dickens and the Workhouse: Oliver Twist and the London Poor – for mentioning this after last week’s post.

• Clerkenwell Green. It is here that Mr Brownlow first comes into contact with Oliver Twist and, mistakenly suspecting him of stealing from him, chases him through the surrounding streets. Interestingly, the grass (which you would expect when talking about a green) has been gone for more than 300 years – so it wasn’t here in Dickens’ time either.

• Barnard’s Inn, Fetter Lane. It was here, at one of London’s Inns of Court, that Pip and Herbert Pocket had chambers in Great Expectations. Barnard’s Inn, now the home of Gresham College, is only one of a number of the Inns of Court with which Dickens and his books had associations – the author lived for a time at Furnival’s Inn while Lincoln’s Inn (off Chancery Lane) features in Bleak House and the medieval Staple Inn on High Holborn makes an appearance in his unfinished novel, The Mystery of Edwin Drood. And, as mentioned last week, Middle Temple also features in his books.

• ‘Dickens House’, Took’s Court. Renamed Cook’s Court in Bleak House, the house – located in a court between Chancery and Fetter Lane – was where the law stationer Mr Snagsby lived and worked in the book. It’s now occupied by music promoter and impresario Raymond Gubbay.

• London Bridge. The bridge, a new version of which had opened in 1831 (it has since been replaced), featured in many of Dickens’ writings including Martin Chuzzlewit, David Copperfield and Great Expectations. Other bridges also featured including Southwark Bridge (Little Dorrit) and Blackfriars Bridge (Barnaby Rudge) and as well as Eel Pie Island, south-west along the Thames River at Twickenham, which is mentioned in Nicholas Nickleby.

We’ve only included a brief sample of the many locations in London related in some way to Dickens’ literary works. Aside from those books we mentioned last week, you might also want to take a look at Richard Jones’ Walking Dickensian London, Lee Jackson’s Walking Dickens’ London or, of course, Claire Tomalin’s recent biography, Charles Dickens: A Life.