In the first of a new regular series looking at “lost” London, Exploring London takes a look at London Bridge.

It’s a commonly confused fact that many first-time visitors to London think Tower Bridge and London Bridge are the same. As Londoners know, London Bridge (pictured right with St Paul’s and the city in the background) lies west of Tower Bridge. It’s not a particularly inspiring bridge having been built in the early Seventies. But there’s been a bridge spanning the Thames here for almost 2,000 years. So what happened to Old London Bridge?

It’s a commonly confused fact that many first-time visitors to London think Tower Bridge and London Bridge are the same. As Londoners know, London Bridge (pictured right with St Paul’s and the city in the background) lies west of Tower Bridge. It’s not a particularly inspiring bridge having been built in the early Seventies. But there’s been a bridge spanning the Thames here for almost 2,000 years. So what happened to Old London Bridge?

The first bridge built across the River Thames on or close to the current site of London Bridge is thought to have been a wooden pontoon bridge constructed by the Romans around 50 AD. It was quickly followed by a more permanent bridge (rebuilt after it was destroyed by Boudicca and her marauding army in 60 AD).

Following the end of the Roman era, the bridge fell into disrepair although it’s known that there was a wooden Saxon bridge on the site by around the year 1,000. A succession of Norman bridges followed the Conquest and in 1176, during the reign of Henry II, construction of a new stone bridge began under the supervision of the priest Peter de Colechurch to service to growing numbers of pilgrims travelling from London to Thomas a Becket’s shrine in Canterbury. The new bridge, which had a chapel dedicated to St Thomas at the centre, wasn’t finished until 1209.

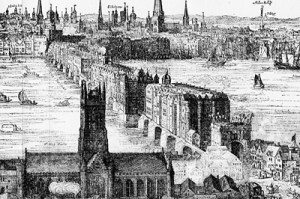

The bridge had 19 arches sitting on piers surrounding by protective wooden ‘starlings’ and a drawbridge and defensive gatehouse. The design of the bridge meant the water shot rapidly through the arches, leading boatmen to describe the practice of taking a vessel between the starlings as “shooting the bridge”.

King John, in whose reign the bridge was completed, licensed the building of houses on the bridge and it soon became a place of business with some 200 shops built upon its length, many of them projecting over the sides and reducing the space for traffic to just four metres. Many of the buildings actually connected at the top, creating a tunnel-like effect.

One of the more remarkable buildings on the bridge was Nonsuch House, built in 1577. A prefabricated building, it had been assembled in the Netherlands before being taken apart, shipped to London, and then reassembled. No nails were used in its construction, just timber pegs.

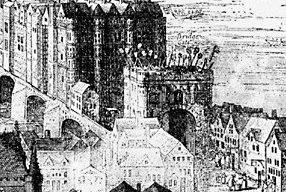

The practice of putting the heads of traitors on pikes above the southern gatehouse (see picture right, dating from 1660) started in 1305 with Scottish rebel William Wallace’s head and continued until it was stopped after 1678 when goldsmith William Stayley’s head was the last to be displayed there. Famous heads to adorn the gateway over the years included Peasant’s Revolt leader Wat Tyler in 1381, rebel Jack Cade in 1450, the former chancellor Sir Thomas More and Bishop John Fisher in 1535, Thomas Cromwell in 1540 and Guy Fawkes in 1606.

The practice of putting the heads of traitors on pikes above the southern gatehouse (see picture right, dating from 1660) started in 1305 with Scottish rebel William Wallace’s head and continued until it was stopped after 1678 when goldsmith William Stayley’s head was the last to be displayed there. Famous heads to adorn the gateway over the years included Peasant’s Revolt leader Wat Tyler in 1381, rebel Jack Cade in 1450, the former chancellor Sir Thomas More and Bishop John Fisher in 1535, Thomas Cromwell in 1540 and Guy Fawkes in 1606.

Some of the bridge’s arches collapsed over the years and had to be restored and there were several fires which destroyed houses upon it, including those which occurred during the Peasants’ Revolt in 1381 and Jack Cade’s rebellion in 1450.

Congestion reached such a state by the 18th century that in 1756 Parliament passed an act which allowed for the demolition of all the shops and houses upon it (it had remained the only bridge spanning the Thames east of Kingston until Westminster Bridge was completed in 1750). This was carried out in 1758-62 along with the removal of two central arches which were replaced with a single wider span.

With traffic only increasing – by 1896, 8,000 people and 900 vehicles were reportedly crossing the bridge every hour – it was clear a new bridge was needed and work on a new stone bridge with five arches – following a design competition won by John Rennie – began in 1824. The old bridge, located about 30 metres east of the new one, remained in use until the new one was opened in 1831. Widening work carried out the early 20th century, however, was too much for the bridge’s foundations and it began to sink.

What followed was one of the strangest episodes in the bridge’s history when in 1967 the Common Council of the City of London decided to sell the bridge. It was sold the following year to Missourian entrepreneur Robert P. McCulloch of McCulloch Oil for $US2.5 million.

Carefully taken apart piece by piece, the bridge was then transported to the desert resort of Lake Havasu City in Arizona in the US and rededicated in 1971.

The current London bridge, designed by Mott, Hay and Anderson, was built from 1967 to 1972 and opened by Queen Elizabeth II in 1973. It stands on the same site as the previous bridge.

As for the song, “London Bridge is falling down”? There’s several stories to explain its origins – one being that it came about as the result of an attack by a joint force of Saxons and Vikings on Danish held London in 1014 during which they pulled the bridge down, and another being that it became popular after Henry III’s wife, Queen Eleanor, was granted the tolls from the bridge by her husband but instead of spending them on maintenance, used it for her own personal use. Hence, “London Bridge is falling down, my fair lady”.

PICTURES: Top: © Steven Allan (istockphoto.com); Bottom – London Bridge (1616) by Claes Van Visscher. SOURCE: Wikipedia.