This year marks the 300th anniversary of the death of Sir Christopher Wren (25th February, 1723), whose designs helped to transform post-Great Fire London.

In a new series we’re looking at 10 locations which help tell Wren’s story but while we’ve previously runs numerous articles focused on the many buildings he designed, in this series the focus is more on his personal life.

First up, it’s one of the most well-known properties related to Wren’s life – the home in which he spent the latter years after his life just outside Hampton Court Palace.

Known as the Old Court House, Wren first came to live in the house after he was appointed Surveyor-General to King Charles II in 1669. His post brought with it lodgings at the royal palaces and at Hampton Court Palace, it was the Old Court House (the property had been built for in 1536 as a wood and plaster house; Wren’s immediate predecessor in the office, Sir John Denham, had rebuilt it partly in brick).

Then in 1708, Queen Anne granted him a 50-year lease on the property, apparently at least partly in lieu of overdue fees he was owed for the building of St Paul’s Cathedral. It’s also believed that the Queen had granted the lease on condition that Wren repair or rebuilt the property.

Wren, who had hitherto only lived intermittently at the property (presumably while working on Hampton Court Palace on the orders of King William III and Queen Mary II), made some major alterations to the property from 1710 onwards (it’s suggested this was done to the designs of Wren’s assistant William Dickinson).

He came to live here on a more permanent basis after he retired from the Office of Works in 1718 and remained here until his death in 1723 (although he didn’t die here – more on that later).

It’s said Wren, whose time as the Royal Surveyor-General spanned the reigns of six monarchs, spent his time here “free from worldly affairs”, choosing to and pass his days ‘in contemplation and studies”.

It was subsequently the home of Wren’s son Christopher (1645-1747) and his grandson Stephen (b 1772). It remained a grace and favour house associated with Hampton Court Palace until 1958.

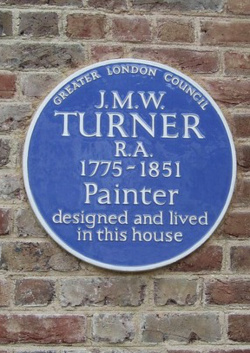

The Grade II* brown and red brick property, which was combined with the house next door in the early 19th century and them divided off in 1960, is now in private ownership and there’s an English Heritage Blue Plaque on the outside wall mentioning Wren’s residence.