Crossing the River Thames just downstream of Richmond and Twickenham Bridge, the Richmond weir and lock complex (actually it’s a half-lock and it also incorporates a footbridge) was built in the early 1890s to maintain a navigable depth of water upstream from Richmond. The Grade II*-listed structure, which is maintained by the Port of London Authority, was formally opened by the Duke of York (later King George V) on 19th May, 1894.

Waterways

Treasures of London – The Golden Hinde II…

Launched in 1973, this full-sized, working replica of the galleon sailed by Elizabethan seafarer and courtier Sir Francis Drake on his circumnavigation of the globe between 1577 and 1580 is moored at St Mary Overie Dock in Bankside.

The ship was made at the behest of two American businessmen, Albert Elledge and Art Blum, who wished to commemorate the 400th anniversary of Sir Francis Drake’s landing on the west coast of North America in 1579.

The ship was made at the behest of two American businessmen, Albert Elledge and Art Blum, who wished to commemorate the 400th anniversary of Sir Francis Drake’s landing on the west coast of North America in 1579.

The ship was designed by Loring Christian Norgaard, a Californian naval architect, who spent three years researching it, drawing on original journals of the crew members and other manuscripts.

The two year job of building the vessel was given to J Hinks & Son who did so in Appledore, North Devon, using traditional methods and tools (with a few modern concessions).

The ship was officially launched from the Hinks shipyard by the Countess of Devon on 5th April, 1973. She sailed out of Plymouth on her maiden voyage in late 1974 and arrived in San Francisco the following May to commemorate Sir Francis’ proclamation of New Albion at a site believed to have been in northern California in 1579.

Since then, the ship has sailed more than 140,000 miles around the world – like its forebear, it has circumnavigated the world – and been feared in various films including Shogun (1979), Drake’s Venture (1980) and St Trinian’s 2: The Legend of Fritton’s Gold (2009).

It has been moored in Southwark since 1996 – it did leave briefly for a visit to Southampton in 2003 – and as well as hosting school visits, is also open for tours and can be booked for private functions.

WHERE: Golden Hinde II, Bankside (nearest Tube station is London Bridge); WHEN: Self-guided tours 10am to 5.30pm daily (check website for other tour times and dates); COST: Various (depending on tour); WEBSITE: www.goldenhinde.com.

A Moment in London’s history…The ‘longest night’…

It was 75 years ago this year – on the night of 10th/11th May, 1941 – that the German Luftwaffe launched an unprecedented attacked on London, an event that has since become known as the ‘Longest Night’ (it’s also been referred to as ‘The Hardest Night’).

It was 75 years ago this year – on the night of 10th/11th May, 1941 – that the German Luftwaffe launched an unprecedented attacked on London, an event that has since become known as the ‘Longest Night’ (it’s also been referred to as ‘The Hardest Night’).

Air raid sirens echoed across the city as the first bombs fells at about 11pm and by the following morning, some 1,436 Londoners had been killed and more than that number injured while more than 11,000 houses had been destroyed along and landmark buildings including the Palace of Westminster (the Commons Chamber was entirely destroyed and the roof of Westminster Hall was set alight), Waterloo Station, the British Museum and the Old Bailey were, in some cases substantially, damaged.

The Royal Air Force Museum records that some 571 sorties were flown by German air crews over the course of the night and morning, dropping 711 tons of high explosive bombs and more than 86,000 incendiaries. The planes were helped in their mission – ordered in retaliation for RAF bombings of German cities – by the full moon reflecting off the river below.

The London Fire Brigade recorded more than 2,100 fires in the city and together these caused more than 700 acres of the urban environment, more than double that of the Great Fire of London in 1666 (the costs of the destruction were also estimated at more than double that of the Great Fire – some £20 million).

Fighter Command sent some 326 aircraft into the fight that night, not all of them over London, and, according to the RAF Museum, the Luftwaffe officially lost 12 aircraft (although others put the figure at more than 30).

By the time the all-clear siren sounded just before 6am on 11th May, it was clear the raid – which turned out to be the last major raid of The Blitz – had been the most damaging ever undertaken upon the city.

Along with the landmarks mentioned above, other prominent buildings which suffered in the attack include Westminster Abbey, St Clement Danes (the official chapel of the Royal Air Force, it was rebuilt but still bears the scars of the attack), and the Queen’s Hall.

Pictured above is a statue of firefighters in action in London during the Blitz, taken from the National Firefighters Memorial near St Paul’s Cathedral – for more on that, see our earlier post here.

For more on The Longest Night, see Gavin Mortimer’s The Longest Night: Voices from the London Blitz: The Worst Night of the London Blitz.

LondonLife – London sunset…

Taken by Murray, this picture captures some of the city’s iconic attractions as it looks across the River Thames to Elizabeth Tower (formerly known as the Clock Tower) at the northern end of the Houses of Parliament just as the sun is setting. Westminster Bridge can be seen to the right while pictured in the foreground, in the middle of a garden located at St Thomas’ Hospital, is the Grade II*-listed sculpture/fountain, Revolving Torsion, which is the work of Russian-born artist Naum Gabo and has been on long-term loan to the hospital since the mid-1970s. Says the photographer: “Funnily enough, I shot this picture handheld and spontaneously as I though I might miss the shot. I then tried to take better ones with a tripod etc – but I think this was my best effort. Spontaneous pictures are always the best…I used to work in St Thomas’ which is behind me in the picture and looked out at this view constantly during the daytime.” PICTURE: Murray/www.flickr.com/photos/muffyc30/.

LondonLife – Quiet afternoon on the canal…

Regent’s Canal in the city’s north. For more on the history of the canal, see our much earlier post here.

10 iconic London film locations…7. The London Eye is saved by the Fantastic Four…

The London Eye features in the background of numerous recent films – everything from 2002’s 28 Days Later to 2004’s Thunderbirds and 2007’s Harry Potter and the Order of the Phoenix.

But the structure, which was built in 1999 and is currently known formally as the Coca-Cola London Eye, has a bigger role in another 2007 film – Fantastic Four: Rise of the Silver Surfer in which the film’s heroes must prevent it toppling into the Thames and a gaping hole that opens up in the river.

Thankfully, in the 2007 film, The Thing (played by Michael Chiklis), Mr Fantastic (Ioan Gruffudd) and the Invisible Woman (Jessica Alba) manage to do so, using their unique powers to save all the people being thrown around inside the Eye’s many pods.

Of course, as an iconic symbol of the city today, the London Eye has also been recreated in several animated films – from Flushed Away to Cars – and is even recreated, tongue-in-cheek, in wood for A Knight’s Tale.

There’s also quite a few films and TV shows which have featured scenes filmed inside the Eye’s pods, including Wimbledon in which one of them plays host to a punch-up.

The area of South Bank around where the Eye is located is a popular spot for films. The OXO Brasserie in the OXO Tower, for example, features in Thor: The Dark World, Millennium Bridge, linking South Bank to St Paul’s Cathedral, can be seen as part of the (imaginary) city on Xander in the film Guardians of the Galaxy and Jubilee Gardens, next to the Eye, was used as a landing pad in Thunderbirds for the T2.

London Pub Signs – The Cutty Sark…

Another Greenwich pub whose name references an aspect of maritime history (see our previous posts on the The Gipsy Moth and the Trafalgar Tavern), this riverside establishment takes its name from a former tea clipper (which, not coincidentally, is on display nearby).

Another Greenwich pub whose name references an aspect of maritime history (see our previous posts on the The Gipsy Moth and the Trafalgar Tavern), this riverside establishment takes its name from a former tea clipper (which, not coincidentally, is on display nearby).

The clipper Cutty Sark was constructed in Dumbarton in 1869 to facilitate the transport of tea from China to Britain in as short a time span as possible. It made its maiden voyage the following year and but only ended up working the tea route for a few years before being used to bring wool from Australia.

Later sold to a Portuguese company, the vessel continued to be used as a cargo ship until she was sold in 1922 and used as training ship, first in Cornwall, and later at Greenhithe in Kent.

In 1954, the vessel found a new permanent dry dock at Greenwich and was put on public display. Damaged by fire in 2007, the ship underwent extensive restoration and is now displayed in a state-of-the-art purpose-built facility which allows you to walk underneath the vessel.

The three level Cutty Sark pub, located at 4-6 Ballast Quay (formerly known as Union Wharf), features a Georgian-style bow windows on the first and second floors (the first floor is home to the Willis Dining Room which has great views of the Thames).

The present Grade II-listed building apparently dates from the early 19th century (although the sign out the front suggests 1795 and it’s been suggested the building was substantially altered in the mid-19th century) but there is evidence of a public house on the location by the early 18th century.

Known at one stage at the Green Man, in 1810 it became the Union Tavern – a reference, apparently, to the union of England and Ireland which took effect in 1801. It took its current name after the Cutty Sark arrived in Greenwich in the 1950s.

For more on the pub, see www.cuttysarkse10.co.uk. For more on the ship, see www.rmg.co.uk/cutty-sark.

10 iconic London film locations…5. Belle at Kenwood House (but not as you know it)…

This is the case of a movie stand-in. While Kenwood House on Hampstead Heath in north London (pictured above) was the real life home of late 18th century figure Dido Elizabeth Belle, the subject of the 2014 Amma Asante-directed film Belle – the movie wasn’t actually shot there.

This is the case of a movie stand-in. While Kenwood House on Hampstead Heath in north London (pictured above) was the real life home of late 18th century figure Dido Elizabeth Belle, the subject of the 2014 Amma Asante-directed film Belle – the movie wasn’t actually shot there.

Thanks to the fact that parts of Kenwood House – in particular the famed Robert Adam interiors – were undergoing restoration at the time, the scenes representing the home’s interiors were instead shot at three other London properties – Chiswick House, Syon Park and Osterley Park, all located in London’s west (West Wycombe Park in Buckinghamshire, meanwhile, was used for the exterior).

While some other scenes were also filmed in London – Bedford Square represented Bloomsbury Square where the London home of Lord Mansfield was located, for example, other locations were also used to represent London – scenes depicting Kentish Town, Vauxhall Gardens and the bank of the River Thames were all actually shot on the Isle of Man, for example.

When the real life Belle – the illegitimate mixed race daughter of an English naval captain who was raised by her great-uncle William Murray, Lord Mansfield (she was played by Gugu Mbatha-Raw in the film; Lord Mansfield by Tom Wilkinson) – is believed to have lived at Kenwood, it was the weekend retreat of Lord Mansfield, then Lord Chief Justice of England (for more on her life, see our previous post here).

Interestingly, the property was also once home to a 1779 painting (previously attributed to Johann Zoffany but now said to be “unsigned”) which depicts Belle and which was apparently the inspiration for the movie. While a copy of the painting still hands at Kenwood, the original now lives at Scone Palace in Scotland.

For more on Belle’s story, see Paula Byrne’s Belle: The True Story of Dido Belle.

LondonLife – Images of London past…

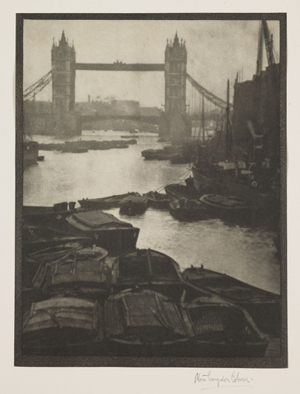

Tower Bridge, here depicted in an image by Alvin Langdon Coburn, taken in about 1910. The image is one of more than 400,000 vintage prints, daguerreotypes and early colour photographs as well as other photography-related objects including the world’s first negative from the Science Museum Group’s 3,000,000 strong photography collection which is being transferred to the Victoria and Albert Museum under an agreement between the two institutions. The images are joining the V&A’s existing collection of 500,000 photographs to create an International Photography Resource Centre, providing the public with a “world class” facility to access what will be the single largest collection on the art of photography on the planet. It’s a reunion for some of the images which were once part of a single collection housed at the South Kensington Museum in the 19th century before it divided into the V&A and the Science Museum. For more on the museums, see www.vam.ac.uk and www.sciencemuseum.ac.uk. PICTURE: © Royal Photographic Society/National Media Museum/ Science & Society Picture Library

Tower Bridge, here depicted in an image by Alvin Langdon Coburn, taken in about 1910. The image is one of more than 400,000 vintage prints, daguerreotypes and early colour photographs as well as other photography-related objects including the world’s first negative from the Science Museum Group’s 3,000,000 strong photography collection which is being transferred to the Victoria and Albert Museum under an agreement between the two institutions. The images are joining the V&A’s existing collection of 500,000 photographs to create an International Photography Resource Centre, providing the public with a “world class” facility to access what will be the single largest collection on the art of photography on the planet. It’s a reunion for some of the images which were once part of a single collection housed at the South Kensington Museum in the 19th century before it divided into the V&A and the Science Museum. For more on the museums, see www.vam.ac.uk and www.sciencemuseum.ac.uk. PICTURE: © Royal Photographic Society/National Media Museum/ Science & Society Picture Library

What’s in a name?…Camden Town…

As with so many London locations, the name Camden Town comes from a previous landowner – but more indirectly it originates with the great 16th and 17th century antiquarian and topographer William Camden.

The story goes like this: late in his life William Camden – author of Britannia, a comprehensive description of Great Britain and Ireland – settled near Chislehurst in Kent on a property which became known as Camden Place.

In the 18th century, the property came into the possession of Sir Charles Pratt, a lawyer and politician (among other things, he was Lord Chancellor in the reign of King George III), who was eventually named 1st Earl of Camden.

It was Pratt who, having come into the possession of the property by marriage, in about 1791 divided up land he owned just to the north of London (which has apparently once been the property of St Paul’s Cathedral) and leased it, resulting in the development of what became Camden Town (Pratt, himself, meanwhile, is memorialised in the name of Pratt Street which runs between Camden High Street and Camden Street).

In 1816, the area received a boost when Regent’s Canal was built through it – the manually operated, twin Camden Lock is located in the heart of Camden Town.

Although it has long carried a reputation of one of the less salubrious of London’s residential neighbourhoods (a reputation which is changing), Camden Town is today a vibrant melting pot of cultures, thanks, in no small part, to the series of markets, including the Camden Lock Market, located there as well as its live music venues.

Past residents have included author Charles Dickens, artist (and Jack the Ripper candidate) Walter Sickert, a member of the so-called ‘Camden Town Group’ of artists, and, in more recent times, the late singer Amy Winehouse.

Of course, the name Camden – since 1965 – has also been that of the surrounding borough.

LondonLife – Australia House’s holy well…

News this week that scientists have confirmed an ancient sacred well beneath Australia House in the Strand (on the corner of Aldwych) contains water fit to drink. The well, believed to be one of 20 covered wells in London, is thought to be at least 900 years old and contains water which is said to come from the now-subterranean Fleet River. Australia’s ABC news was recently granted special access to the well hidden beneath a manhole cover in the building’s basement and obtained some water which was tested and found to be fit for drinking. It’s been suggested that the first known mention of the well – known simply as Holywell (it gave its name to a nearby street now lost) – may date back to the late 12th century when a monk, William FitzStephen, commented about the well’s “particular reputation” and the crowds that visited it (although is possible his comments apply to another London well). Australia House itself, home to the Australian High Commission, was officially opened in 1918 by King George V, five years after he laid the foundation stone. The Prime Minister of Australia, WM “Billy” Hughes, was among those present at the ceremony. The interior of the building has featured in the Harry Potter movies as Gringott’s Bank. PICTURE: © Martin Addison/Geograph.

News this week that scientists have confirmed an ancient sacred well beneath Australia House in the Strand (on the corner of Aldwych) contains water fit to drink. The well, believed to be one of 20 covered wells in London, is thought to be at least 900 years old and contains water which is said to come from the now-subterranean Fleet River. Australia’s ABC news was recently granted special access to the well hidden beneath a manhole cover in the building’s basement and obtained some water which was tested and found to be fit for drinking. It’s been suggested that the first known mention of the well – known simply as Holywell (it gave its name to a nearby street now lost) – may date back to the late 12th century when a monk, William FitzStephen, commented about the well’s “particular reputation” and the crowds that visited it (although is possible his comments apply to another London well). Australia House itself, home to the Australian High Commission, was officially opened in 1918 by King George V, five years after he laid the foundation stone. The Prime Minister of Australia, WM “Billy” Hughes, was among those present at the ceremony. The interior of the building has featured in the Harry Potter movies as Gringott’s Bank. PICTURE: © Martin Addison/Geograph.

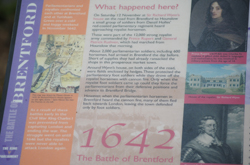

10 London ‘battlefields’ – 7. Battle of Brentford…

Yes, we’re a bit out of order here given we looked at the subsequent Battle of Turnham Green last week, but today we’re taking a look at the Civil War fight known as the Battle of Brentford.

As recounted last week, having taken Banbury and Oxford in the aftermath of the Battle of Edgehill, the Royalist army marched along the Thames Valley toward London where a Parliamentarian army under the Earl of Essex waited.

Having arrived at Reading to the west of London, King Charles I, apparently unconvinced peace talks were heading in the right direction, ordered Prince Rupert to take Brentford in order to put pressure on the Parliamentarians in London.

Having arrived at Reading to the west of London, King Charles I, apparently unconvinced peace talks were heading in the right direction, ordered Prince Rupert to take Brentford in order to put pressure on the Parliamentarians in London.

On 12th November, 1642, up to 4,600 Royalists under the command of the prince engaged with two Parliamentarian infantry regiments at Brentford, one of the key approaches the City of London. The Parliamentarians were under the command of Denzil Hollis (who wasn’t present) and Lord Brooke – various estimates put their number at between 1,300 and 2,000 men.

Prince Rupert’s men – consisting of cavalry and dragoons – attacked at dawn under the cover of a mist. An initial venture to take a Parliamentarian outpost at the house of Royalist Sir Richard Wynne was repulsed by cannon fire but Sir Rupert ordered a Welsh foot regiment to join the fight and the outpost was quickly taken.

The Cavaliers then pushed forward across the bridge over the River Brent (which divided the town) and eventually drove the Parliamentarians from the town and into the surrounding fields (part of the battle was apparently fought on the grounds of Syon House – pictured at top).

Fighting continued into the late afternoon before the arrival of a Parliamentarian infantry brigade under the command of John Hampden allowed the Roundheads to withdraw.

About 170 are believed to have died in the battle (including a number who drowned fleeing the fighting). Followed by the sack of the town, the battle was a success for the Royalists who apparently captured some 15 guns and about 400 prisoners. The captured apparently included Leveller John Lilburne, a captain in Brooke’s regiment.

The Royalists and Parliamentarians met again only a few days later – this time at Turnham Green (for more on that, see last week’s post).

Incidentally, this wasn’t the first battle to be fought at Brentford. Some time over the summer of 1016, English led by Edmund Ironside clashed with the Danes under the soon-to-be-English king Canute. Edmund was victorious on the day, one of a series of battles he fought with Canute.

Meanwhile, more than 1000 years earlier, it was apparently at Brentford that the British under the King Cassivellaunus fought with Julius Caesar’s men in 54 BC on their approach to St Albans (Verulamium).

A pillar stands High Street in Brentford commemorating all three battles while there is an explanatory plaque about the battle in the grounds of Syon Park.

For more the Battles of Brentford and Turnham Green, see www.battlefieldstrust.com/brentfordandturnhamgreen.

LondonLife Special – Expressing solidarity with Paris…

A week ago tonight the world was left reeling in the wake of the devastating series of coordinated terrorist attacks in Paris, France, which have left 132 people dead and hundreds more wounded. In the wake of the attacks, national landmarks across the world were lit up in the colours of the French flag, among them, the London Eye, overlooking the River Thames. PICTURE: Martin Sylvester/Digital Concepts.

10 London ‘battlefields’ – 2. ‘London Bridge is falling down’…

We’ve touched on this story before but it’s worth a revisit as part of this series. London changed hands several times during the later half of the first millennium as the Anglo-Saxons fought Vikings for control of the city, meaning the city was the site of several battles during the period.

We’ve touched on this story before but it’s worth a revisit as part of this series. London changed hands several times during the later half of the first millennium as the Anglo-Saxons fought Vikings for control of the city, meaning the city was the site of several battles during the period.

One of the most memorable (or so legend has it, there are some archaeologists who believe the incident never took place) was the battle in 1014 in which London Bridge – then a timber structure (today’s concrete bridge is pictured above) – was pulled down. A story attributed to the Viking skald or poet Ottarr the Black but not found in Anglo-Saxon sources, the event, if it did take place, did so against the backdrop of an ongoing conflict between the Danes and Anglo-Saxons.

Anglo-Saxon London had resisted several attempts at being taken by the Vikings – a fire was recorded in the city in 982, possibly caused by a Viking attack – and in 994, the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle reports that a fleet of 94 Danish and Norwegian ships were repelled with prejudice. Further attacks was driven back in 1009 and it wasn’t until 1013 that the city finally submitted to Danish rule after Sweyn Forkbeard had already claimed Oxford and Winchester.

But Sweyn, the father of the famous King Canute (Cnut), didn’t hold it long – he died on 3rd February the following year.

The deposed Anglo-Saxon King Æthelred II (also spent Ethelred, he was known as ‘the Unready’) – who had been forced to flee from London, which he used as his capital, to what is now Normandy thanks to Sweyn’s depredations – is said to have seized his chance and along with the forces of his ally, the Norwegian King Olaf II, he sailed up the Thames to London in a large flotilla.

The Danish had taken the city, occupying both the city proper and Southwark, and were determined to resist. According to the Viking account, they lined the timber bridge crossing the river and rained spears down on the would-be invaders. (The bridge, incidentally, had apparently been built following the attack in 993, ostensibly to block the river and prevent further incursions further upstream – there is certainly archaeological evidence that a bridge existed in about the year 1000).

Not to be beaten, Æthelred’s forces, using thatching stripped from the rooves of nearby houses to shield themselves, managed to get close enough to attach some cables to the bridge’s piers, pulling the bridge down and winning the battle, retaking the city.

There’s much speculation that the song London Bridge is Falling Down was inspired by the incident but it, like much of this story itself, remains just that – conjecture (although Ottarr’s skald does sound rather familiar).

The bridge was subsequently rebuilt and King Æthelred died only two years later, on 23rd April, 2016. The crown subsequently passed to his son Edmund Ironside but he too died after ruling for less than a year leaving Viking Canute to be crowned king.

PICTURE: http://www.freeimages.com

What’s in a name?…Kew…

Famed as the location of the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew is a Thames-side suburb in London’s west.

Famed as the location of the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew is a Thames-side suburb in London’s west.

It’s the riverside location which gives the area its name – Kew is apparently a corrupted form of Cayho, a word first recorded in the early 14th century which is itself made of two words referring to a landing place (the ‘Cay’ part) and a spur of land (the ‘ho’ part). The latter may refer in this case to the large “spur” of land upon which Kew is located, created by a dramatic bend in the Thames. The former may refer to a ford which crossed the river here (explaining the name of Brentford on the other side).

While the area had long been the home of a small hamlet for the local farming and fishing community, more substantial houses began to be developed in Kew in the late 15th and early 16th centuries thanks to the demand for homes for courtiers attending the King Henry VII and his successors at nearby Richmond Palace (the royal connections of the area in fact go back much further to the early Middle Ages).

But it was during the Georgian era, when the Royal Botanic Gardens were founded and Kew Palace, formerly known as the Dutch House, became a royal residence (it is pictured above), that Kew really kicked off (and by the way, Kew Palace is not the only surviving 17th century building in the area – West Hall, once home of painter William Harriot, is also still here).

While King George II and his wife Queen Caroline used Richmond Lodge, now demolished but then located at the south end of what is now the gardens, as their summer residence, they thought Kew Palace would make a good home for their three daughters (their heir, Frederick, Prince of Wales, lived opposite his sisters at the now long-gone White House). Kew Palace, meanwhile, would later be a residence of other members of the Royal Family as well, including King George III during his bouts of madness.

Other buildings of note from the Georgian era in Kew include Queen Charlotte’s Cottage, a thatched property built between 1754 and 1771 and granted to Queen Charlotte by her husband, King George III (like the palace, it now lies within the grounds of Kew Gardens). St Anne’s Church, located on Kew Green, dates from 1714 and hosts the tombs of artists Johann Zoffany and Thomas Gainsborough.

In 1840, the gardens which surrounded the palace were opened to the public as a national botanic garden and the area further developed with the opening of the railway station in 1869, transforming what was formerly a small village into the leafy largely residential suburb which we find there today (although you can still find the village at its heart).

As well as Kew Gardens (and Kew Palace), Kew is today also the home of the National Archives, featuring government records dating back as far as 1086.

Lost London – The Great Conduit…

Located at the junction of Cheapside and Poultry, the Great Conduit, also known as the Cheapside Standard, was a famous medieval public fountain.

Located at the junction of Cheapside and Poultry, the Great Conduit, also known as the Cheapside Standard, was a famous medieval public fountain.

The Great Conduit (the word conduit refers to column fountains fitted with ‘cocks’ or taps for dispensing the water) gave access to water piped using gravity four kilometres from the Tyburn into the City largely via lead pipes.

It was constructed by the City Corporation from the mid-13th century after King Henry III approved the project in 1237. It was rectangular-shaped timber building with an elevated lead tank inside from which the water was drawn.

It took the name ‘Great’ after further conduits were built further west in Cheapside in the 1390s. There were at least 15 conduits or standards scattered about the City by the time of the Great Fire in 1666.

It was rebuilt several times over its life, notably in the reign of King Henry VI, but after being severely damaged in the fire was deemed irreparable and orders were given for it to be taken down in 1669 (many houses by then had alternate water supplies, notably from the New River project). From the 1360s, management of the conduit was the responsibility of four wardens, maintaining the pipes and charging professional water carriers and tradesmen who required water by allowing free

The Cheapside Conduit was a notable landmark – some executions and other punishments were carried out here, speeches were made from here and the conduit building itself was used as a place for posting information. And to celebrate special occasions it was made to flow with wine – this took place in 1432 when King Henry VI marched through London after being crowned King of France, at the coronation of Queen Margaret in 1445 and at the wedding procession of King Henry VIII’s queen Anne Boleyn in 1533.

The substructure of the Great Conduit was rediscovered at the end of the 19th century and again in the 1990s. A plaque marking the location of the Great Conduit at the eastern end of Cheapside was unveiled in late 1994 by Thames Water and the Worshipful Company of Water Conservators. There’s also a memorial set into the pavement over the substructure.

Special – Queen Elizabeth II becomes longest reigning monarch…

We interrupt our regular programming this week to mark the day in which Queen Elizabeth II becomes the UK’s longest reigning monarch, passing the record reign of her great-great-grandmother, Queen Victoria.

The milestone of 63 years, seven months and two days (the length of Queen Victoria’s reign) will reportedly be passed at about 5.30pm today (the exact time is unknown as the Queen’s father, King George VI, passed away in his sleep).

While the Queen, now 89 (pictured here in 2010), will pass the day in Scotland attending official duties, in London Prime Minister David Cameron will lead tributes in the House of Commons.

As we go to press a flotilla of vessels – including Havengore and Gloriana – will process along the River Thames between Tower Bridge, open as a sign of respect, and the Houses of Parliament. As they passed HMS Belfast, the ship will fire a four gun salute.

Today is the 23,226th day of the Queen’s reign during which she has met numerous major historical figures – from Charles de Gaulle to Nelson Mandela – and seen 12 British Prime Ministers come and go.

London Pub Signs – The Mawson Arms/The Fox and Hounds…

This curiously named Chiswick institution, one of few pubs in England with two names, owes its existence to the brewery located next to the terraces in Mawson Row.

Thomas Mawson founded the brewery on the site in the late 1600s/early 1700s and it eventually became what is now known as Fuller’s Griffin Brewery located a few doors down from the pub.

Thomas Mawson founded the brewery on the site in the late 1600s/early 1700s and it eventually became what is now known as Fuller’s Griffin Brewery located a few doors down from the pub.

The Grade II*-listed building in which the pub is located dates from about 1715 when the terrace of five houses was constructed for Mawson.

The 18th century poet Alexander Pope was among residents at number 110 (between 1716-1719, when he published his translation of The Iliad and his first collected works). A function room in the pub now bears his name and there’s a blue plaque mentioning his stay on the outside.

While there had long been a pub here called the Fox and Hounds, in the late 19th century, the old pub was extended into the corner building and gained its second name, The Mawson Arms.

The pub, only a short walk away from the Thames, now serves as the starting point for a tour of the brewery. It’s traditionally been a favoured watering hole of brewery workers.

For more, see www.mawsonarmschiswick.co.uk.

LondonLife – See the Thames…in Blackfriars station…

This is one of a series of works by renowned photographer Henry Reichhold which features in the exhibition Thames – Heart of London, currently on show at Blackfriars Thameslink railway station. Thameslink and JCDecaux have provided 49 platform advertising sites for the display, part of the Totally Thames celebrations taking place throughout September. The photographs, which measure 2.5 metres long, are an attempt to capture the character of the Thames as it winds its way through the city and were taken from a series of notable vantage points including the Shard, City Hall, OXO Tower, One Canada Square, Southbank Tower and the Houses of Parliament. As well as the river itself, they also capture some of the many events which have taken place upon it – from the Diamond Jubilee Pageant to New Year’s Day celebrations. Each image has taken between one and three weeks to create from up to 100 separate photographs – selected out of more than 800 taken on a single day – which have then been put together in a stunning panorama. New York-born Reichhold says the process of “extracting” the final image is “never the same”. “The camera is very stubborn about creating a ‘mechanical’ view and it is the reinterpretation of these files to in some way reflect what the human eye sees that I find so troublesome and fascinating.” The exhibition is at Blackfriars Station, 179 Queen Victoria Street, London, and runs until 30th September. Entry is free to passengers with a valid GTR train ticket and to holders of a 10p platform ticket.

This Week in London – Tall ships at Greenwich; immersive art at Tate Britain; and, ‘Nature’s Bounty’ at Kew…

• It’s all about big masted ships at Greenwich this Bank Holiday weekend as up to 15 ships drop anchor at the Royal Greenwich Tall Ships Festival. Two tall ships, the Dar Mlodziezy and Santa Maria Manuela, will be moored on Tall Ships Island in the river at Maritime Greenwich (accessed via MBNA Thames Clippers) while an additional 13 ships will be taking people on cruises from their base at Royal Arsenal Woolwich (tickets can be booked via Sail Royal Greenwich). On Saturday, a free family festival will be held in Woolwich Town Centre and at Royal Arsenal Riverside with music, roving entertainers, food and other activities including a fireworks display on the river at 10pm (fireworks can also be seen on Thursday, Friday and Sunday nights on the river at Maritime Greenwich at around 9.15pm). For more information – including how and where to book tickets, see www.royalgreenwich.gov.uk/tallships2015.

• An immersive art project allowing visitors to engage with paintings in a multi sensory experience opened at Tate Britain on Milbank yesterday. Tate Sensorium has won this year’s annual IK Prize, presented by the Tate and supported by the Porter Foundation, awarded for a project which uses innovative technology to enable the public to explore the gallery’s collection in new ways. The display features four works by celebrated figures in 20th century painting: Francis Bacon’s Figure in a Landscape (1945), David Bomberg’s In the Hold (c 1913-1914), Richard Hamilton’s Interior II (1964) and John Latham’s Full Stop (1961). As part of the experience, which has been produced by creative studio Flying Object in conjunction with a cross-disciplinary team, visitors are offered the chance to wear biometric measurement wristbands to record the emotional impact of the experience. Admission to exhibition in gallery 34 is free but tickets are limited. Runs until 20th September. For more, see www.tate.org.uk/sensorium.

• A series of detailed paintings of fruit, vegetables and edible plants from all over the world goes on show at the Shirley Sherwood Gallery of Botanical Art at Kew Gardens on Saturday. Nature’s Bounty features works from the Shirley Sherwood and Kew collections including works from the 19th century text, Fleurs, Fruits et Feuillages Chosis de la Flore et de la Pomona de L’ile de Java drawn by botanical artist Berthe Hoola Van Nooten as well as works from the Shirley Sherwood and Kew collections. The exhibition runs until 31st January. Admission charge applies. For more, see www.kew.org.

Send all items for inclusion to exploringlondon@gmail.com.