Now a few scant ruins located in Southwark, this was once the opulent palace of one of the most powerful clergymen in the country.

We’ve written about Winchester Palace before but we thought it was worth a second look in our current series.

Now a few scant ruins located in Southwark, this was once the opulent palace of one of the most powerful clergymen in the country.

We’ve written about Winchester Palace before but we thought it was worth a second look in our current series.

This Borough pub’s name comes from 19th century Field Marshall Colin Campbell Clyde (Lord Clyde).

Clyde (1792-1863) was a Scottish carpenter’s son who joined the military at age 16 and fought in many campaigns during the first half of the 19th century including the Peninsular War of 1808-1814, the War of 1812 in the United States, the First Opium War in China in 1842, and in India during the Second Anglo-Sikh War in 1848-49.

During the Crimean War, Clyde led the Highland Brigade at the Battle of the Alma and repulsed the Russian attack on Balaclava. He become Commander-in-Chief, India, during the Indian Mutiny in 1857 and relieved the siege of Lucknow in India the same year.

Clyde was raised to the peerage in 1858. Her died in Chatham on 14th August, 1863, and was buried in Westminster Abbey.

A pub was first erected on the site at 27 Clennam Street (on the corner with Ayers Street) at the time of his death in 1863 by brewers in East London (originally known as the Black Eagle Brewery, the name Truman, Hanbury, Buxton & Co – which appears on the pub’s exterior – was being used for the brewery by 1889).

It was rebuilt in 1913 – the present frontage dates from that period – and is now Grade II-listed thanks to its architecture, which exemplifies the development of the ‘house style’ in pub architecture of the early 20th century.

The signage on the pub depicts Lord Clyde wearing the insignia of the Knight Commander of the Bath, an honour he was awarded in 1849 for his services in the Sikh War. There is a statue of him in Waterloo Place in London.

For more, head to https://www.facebook.com/lordclydeborough/.

This pub, located in Southwark, just north of Borough Market (and Southwark Cathedral), owes its name to the proximity of the river and the traditional practice of mudlarking – a word used to describe the idea of scavanging the banks of the Thames for valuables.

Mudlarking rose to prominence in the 18th and 19th centuries and the mudlarks were often children, mostly boys, who would undertake the dangerous activity of scavanging the foreshore of the tidal Thames on a daily basis in an effort to supplement the family income.

The 19th century journalist Henry Mayhew wrote about mudlarks he encountered on the river, including a nine-year-old who, dressed in nothing but trousers that had been worn away to shorts, had apparently already been about the activity for three years.

The mudlarks were after anything that could be sold for a small income – coal, ropes, bones, iron and copper nails.

The practice continues today – and has unearthed some fascinating historic finds – but anyone wanting to do so needs a permit from the Port of London Authority (and must respect rules around their finds that are of an historical nature).

The pub, meanwhile, originally dates from the mid-1700s and used to feature child mudlarks on its sign (it now has a hand holding a mudlark’s find of a coin).

It is (unsurprisingly, given the location) said to be popular with market traders and attendees.

The pub, located on Montague Close, is these days part of the Nicholson’s chain. For more, see https://www.nicholsonspubs.co.uk/restaurants/london/themudlarklondonbridge#/

London’s oldest surviving pie and mash shop is generally said to be the establishment of M Manze near Tower Bridge.

The shop was opened in 1902 by Michele Manze, who was born in Ravello, southern Italy, and has been serving their pies and mash with green liquor (a parsley sauce) and eels ever since.

Manze had arrived in London with his family when just three-years-old and settling in Bermondsey, south of the Thames, has started what was originally an ice supply business which soon started selling ice-cream. But Michele branched out into the pie and mash business.

The first shop under his name was at 87 Tower Bridge Road. It was established by Robert Cooke (of a famed family of pie and mash purveyors) in 1891 and Manze took over soon after his marriage to Cooke’s widowed daughter, Ada Poole.

Manze opened a second in Southwark Park Road in 1908. Three further shops followed – two in Poplar which were destroyed in World War II – one at Peckham High Street in 1927.

Several of his brothers including Luigi, meanwhile, opened their own pie and mash shops and so it’s said there were 14 pie, mash and eel shops bearing the Manze name by 1930.

That number has since been whittled down for various reasons and there are today there are three M Manze pie and mash shops – the Tower Bridge Road and Peckham establishments and a third which was opened in Sutton in 1998.

The Tower Bridge Road shop was damaged during World War II when the front of it was blown out.

Famous clientele have apparently included Roy Orbison, Rio Ferdinand and David Beckham and it even appeared in a music video of Elton John’s.

For more, see https://www.manze.co.uk

This district of London, which lies to the south-east of Peckham in the London Borough of Southwark, is believed to owe its name to a local tavern named, you guessed it, the Nun’s Head on the linear Nunhead Green (there’s still a pub there, called The Old Nun’s Head, in a building dating from 1905).

There may well have been actual nuns here (from which the tavern took its name) – it’s suggested that there was a nunnery here which may have been connected to the Augustinian Priory of St John the Baptist founded in the 12th century at Holywell (in what is now Shoreditch).

A local legend gets more specific. It says that when the nunnery was dissolved during the Dissolution, the Mother Superior was executed for her opposition to King Henry VIII’s policies and her head was placed in a spike on the site near the green where the inn was built.

While the use of the name for the area goes back to at least the 16th century, the area remained something of a rural idyll until the 1840s when the Nunhead Cemetery, one of the “Magnificent Seven” cemeteries of Victorian London, was laid out and the area began to urbanise.

A fireworks manufactory – Brocks Fireworks – was built here in 1868 (evidenced by the current pub, The Pyrotechnists Arms). The railway arrived in 1871.

St Antholin’s Church was built in 1877 using funds from the sale of the City of London church, St Antholin’s, Budge Row, which was demolished in 1875. St Antholin’s in Nunhead was destroyed during the Blitz and later rebuilt and renamed St Antony’s (the building is now a Pentecostal church while the Anglican parish has been united with that of St Silas).

There’s also a Dickens connection – he rented a property known as Windsor Lodge for his long-term mistress, actress Ellen Ternan, at 31 Lindon Grove and frequently visited her there (in fact, it has even been claimed that he died at the property and his body was subsequently moved to his home at Gad’s Hill to avoid a scandal).

Nunhead became part of the Metropolitan Borough of Camberwell in 1900. These days, it’s described by Foxtons real estate agency as “a quiet suburb with pretty roads and period appeal”.

An inhabitant of Roman Londinium some 1,600 years ago, a wealthy Roman woman was laid to rest in a stone sarcophagus in what is now Southwark.

Her rest was not uninterrupted. At some point – reported as during the 16th century – thieves broke into her coffin, allowing earth to pour in. The sarcophagus was then reburied and and lay undisturbed until June, 2017, when it was found at a site on Harper Road by archaeologists exploring the property prior to the construction of a new development.

Subsequent analysis found that almost complete skeleton of a woman as well as some bones belonging to an infant (although it remains unclear if they were buried together). Along with the bones was a tiny fragment of gold – possibly belonging to an earring or necklace – and a small stone intaglio, which would have been set into a ring, and which is carved with a figure of a satyr.

The burial, which took place at the junction of Swan Street and Harper Road, is estimated to have taken place between 86 and 328 AD and the woman was believed to be aged around 30 when she died.

It’s clear from the 2.5 tonne sarcophagus that the woman was of high status – most Londoners of this area were either cremated or buried in wooden coffins. The sarcophagus was only one of three found in London in the past three decades.

Think of fire in relation to London and the events of 1666 no doubt spring to mind. But London has had several other large fires in its history (with a much higher loss of life), including during the reign of King John in July, 1212.

The fire started in Southwark around 10th July and the blaze destroyed most of the buildings lining Borough High Street along with the church of St Mary Overie (also known as Our Lady of the Canons and now the site of Southwark Cathedral) before reaching London Bridge.

The wind carried embers across the river and ignited buildings on the northern end before the fire spread into the City of London itself (building on the bridge had been authorised by King John so the rents could be used to help pay for the bridge’s maintenance).

Many people died on the bridge after they – and those making their way south across the bridge to aid people in Southwark (or perhaps just to gawk) – were caught between the fires at either end, with some having apparently drowned after jumping off the bridge into the Thames (indeed, it’s said that some of the crews of boats sent to rescue them ended up drowning themselves after the vessels were overwhelmed).

Antiquarian John Stow, writing in the early 17th century, stated that more than 3,000 people died in the fire – leading some later writers to describe the disaster as “arguably the greatest tragedy London has ever seen”.

But many believe this figure is far too high for a population then estimated at some 50,000. The oldest surviving account of the fire – Liber de Antiquis Legibus (“Book of Ancient Laws”) which was written in 1274 and mentions the burning of St Mary Overie and the bridge, as well as the Chapel of St Thomas á Becket built upon it – doesn’t mention a death toll.

London Bridge itself survived the fire thanks to its recent stone construction but for some years afterward it was only partly usable. King John then raised additional taxes to help rebuild destroyed structures while the City’s first mayor, Henry Fitz Ailwyn, subsequently apparently joined with other officials in creating some regulations surrounding construction with fire safety in mind.

The cause of the fire remains unknown.

This small walled garden, located in Southwark, for centuries served as a burial site for the poor of the area nd by the time of its closing in 1853, was the location of some 15,000 burials.

The graveyard is said to have started life as an unconsecrated burial site for ‘Winchester Geese’, sex workers in the medieval period who were licensed to work in the brothels of the Liberty of the Clink by the Bishop of Winchester.

Excavations carried out in the 1990s confirmed a crowded graveyard was on the site.

While the site had been neglected for years following its closure, in 1996 local writer John Constable and a group he co-founded, the Friends of Crossbones, began a campaign to transform Crossbones into a garden of remembrance – something which has happened thanks to their efforts and those of the Bankside Open Spaces Trust and others.

The garden provides a contemplative space for people to pay their respects to what have become known as the “outcast dead”.

A plaque, funded by Southwark Council, was installed on the gates in 2006 which records the history of the site and the efforts to create a memorial shrine.

WHERE: Crossbones Graveyard, Redcross Way, Southwark (nearest Tube stations are London Bridge and Borough); WHEN: Wednesdays, Thursdays and Fridays 12 to 2pm; COST: Free; WEBSITE: www.bost.org.uk/crossbones-graveyard.

Long thought to have been London’s oldest public statue (and certainly the oldest of a monarch), this statue of Anglo-Saxon King Alfred the Great stands in a quiet location in Trinity Church Square in Southwark.

The statue – which depicts the bearded king robed and wearing a crown – was believed to have medieval origins with some suggesting it was among those which north face of Westminster Hall since the 14th century and were removed by Sir John Soane in 1825.

But recent conservation work has shown that half of the statue is actually much older. In fact, it’s believed that the lower half of the figure was recycled from a statue dedicated to the Roman goddess Minerva and is typical of the sort of work dating from the mid-second century.

Measurements of the leg of the lower half indicate the older statue stood some three metres in height, according to the Heritage of London Trust. It is made of Bath Stone and was likely carved by a stone worker located on the continent. It probably came from a temple.

The top half, meanwhile is made of Coade stone and, given that wasn’t invented by Eleanor Coade until around 1770, the creation of the statue as it appears today is obviously much later than was originally suspected which may give credence to theory that it was one of a pair – the other representing Edward the Black Prince – made for the garden of Carlton House in the late 18th century.

Putting the two parts of the statue together would have required some specialised skills.

The Grade II-listed statue has stood in the square since at least 1826. Much about who created it still remains a mystery. The fact it incorporates a much older statue means the question of whether it is in fact London’s oldest outdoor public statue remains a matter of some debate.

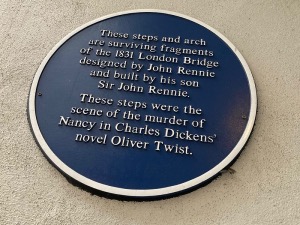

We close our series of historic London stairs with a stairway that has raised its share of controversy in recent years, largely due to the plaques associated with it.

The steps, which are located in Southwark at the southern end of London Bridge and which lead down to Montague Close, are a remnant of the John Rennie-designed London Bridge which was completed in 1831 and which was replaced in the mid-20th century (and which was sold off and relocated to Lake Havasu in the US).

The controversy arises through the plaques associated with the steps which state that the steps where the scene of the murder of Nancy in Charles Dickens’ Oliver Twist. There’s a couple of problems with that claim.

The first is that Nancy wasn’t murdered here in the book – it is in their lodgings that Bill Sikes kills Nancy believing she has betrayed him. The confusion probably comes about because the musical Oliver! did set Nancy’s murder on the steps.

The bridge does, however, play a role in the book and have a connection to Nancy and its probably due to this connection that it has its name, Nancy’s Steps.

Because it was on steps located here – “on the Surrey bank, and on the same side of the bridge as Saint Saviour’s Church [now known as Southwark Cathedral]” that Nancy talks to Oliver’s benefactors while Noah Claypole eavesdropped on the conversation (which leads him reporting back to Sikes and eventually to her murder).

The second error made in the plaque is that Rennie’s bridge (and hence the steps) was completed in 1831 and with Oliver Twist published in serial form just a few years later can’t be the “ancient” bridge referred to in the text. The reference can only relate to the medieval bridge which occupied the site for hundreds of years until it was demolished following the completion of Rennie’s bridge.

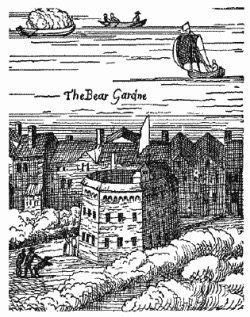

The Bear Garden was among numerous structures built in Southwark during the Elizabethan era for public amusement: in this case the “amusement” being what we now see as the rather cruel activities of bear and bull baiting and other “sports” involving animals.

Built sometime prior to the 1560s, the Bear Garden (also written as Beargarden) itself was a polygonal wooden, donut-shaped structure, much like the theatres such as the Rose and Globe, where the activities took part on the floor in the middle while the audience sat around the donut’s ring.

While it’s known it was located in Bankside (among several other premises showing animal sports), its exact location continues to be a matter of debate (and it is thought to have moved location at least once).

The Bear Garden was patronised by royalty – Queen Elizabeth I apparently visited with the French and Spanish ambassador – but it was also marked by tragedy when part of the tiered seating collapsed in 1583, killing eight people and forcing the premises to close down for a brief period.

It was torn down in 1614 and replaced with the Hope Theatre with the intention of it serving as a dual purpose premises, providing both stage plays and animal sports like bear-baiting, but the latter eventually won out and it simply became known once again as the Bear Garden.

The Hope may have pulled down in the 1650s after animal sports were banned by the Puritans (the Commonwealth commander Thomas Pride was apparently responsible for putting down or shooting the last seven bears). Whether it was demolished or not, it was again in use after the Restoration – Samuel Pepys and John Evelyn both visited during this period – but the last mention of it was in the 1680s.

The street named Bear Gardens in modern Southwark stands today in the approximate area where the Bear Garden is generally thought to have been located.

We’ve finished our series on London sites related to the story of Thomas Becket. Before we move on to our next special series, here’s a recap…

We’ll launch our new series next Wednesday.

Following Thomas Becket’s brutal murder in Canterbury Cathedral in 1170, King Henry II is ordered by Pope Alexander III to perform acts of penance for his death, going on a public pilgrimage to Canterbury where he spent a night in prayer at Becket’s tomb and was whipped by monks.

Becket’s renown, meanwhile, quickly grew in the aftermath of his death and miracles soon began to be attributed to him. And then, little over two years after he was killed, the Pope declared him a saint. It’s believed that soon after that, in 1173, St Thomas’ Hospital in Southwark- which had been founded a couple of years earlier – was named in commemoration of him.

The hospital was run by a mixed-gendered order of Augustinian canons and canonesses, believed to be of the Priory of St Mary Overie, and provided shelter and treatment for the poor, sick, and homeless. Following a fire in the early 13th century, the hospital was relocated to a site on what is now St Thomas Street.

In the 15th century, Dick Whittington endowed a ward for expectant unmarried mothers at the hospital and in 1537, it was the location for the printing of one of the first English Bibles – which is commemorated in a plaque at the former site of the hospital.

When the monastery at Southwark, which oversaw the hospital – also referred to as the Hospital of St Thomas the Martyr, was closed in 1539 during the Dissolution, the hospital too was closed. It did reopen a decade later but was dedicated to St Thomas the Apostle instead of St Thomas Becket (and has remained so since). The name change was political – King Henry VIII had ‘decanonised” St Thomas Becket as part of his reform of the church in England.

The hospital was rebuilt from the end of the 17th century (the long-deconsecrated Church of St Thomas in St Thomas Street, home to the Old Operating Theatre & Herb Garrett, is the oldest surviving part of this rebuild) but it left Southwark in 1862 when the site was compulsorily acquired to make way for the construction of the Charing Cross railway viaduct from London Bridge Station.

Following a temporary relocation to Royal Surrey Gardens in Newington, it moved into new premises at Lambeth – across the river from the Houses of Parliament – in 1871. It has since been rebuilt and merged with Guy’s Hospital.

Correction: Apologies – we had typo in the copy – the date Becket was made a saint was, of course, 1173!

A waterway said to have been cut by the Viking Canute (also spelled Cnut) in the 11th century, the canal, according to the story, was constructed so his fleet of ships – blocked by London Bridge – could get upstream.

The story goes that in May, 1016, the Dane Canute (and future King of England), led an army of invasion into England to reclaim the throne his father, Sweyn Forkbeard, had first won three years earlier.

Canute needed to get his ships upriver of London Bridge to besiege the city which was held by the Saxons under Edmund Ironside (made king in April after his father Athelred’s death) but was blocked by the fortified, although then wooden, London Bridge.

So Canute gave orders for the digging of a trench or canal across some part of Southwark so his ships could pass into the river to the west of the bridge and he could encircle the city.

The canal – also known as ‘Canute’s Trench’ – was duly dug and the city was besieged – although the Vikings lifted the siege without taking the city (which does seems like a lot of work for not much result in the end) and the war was eventually decided elsewhere.

Various routes of the canal have been posited as possibilities – including the suggestion that there was an entry at Rotherhithe (Greenland Dock has been sited as one location) and exit somewhere near Lambeth or further south at Vauxhall (and one possibility is that Canute, rather than digging a long canal, simply cut through the bank holding back the Thames on either side of London Bridge and flooded the lands behind).

Various waterways have also been identified with it including the River Neckinger, parts of which survive, and the now lost stream known as the Tigris.

Whether the canal actually existed – and what form it took – remains a matter of some debate (although the low-lying, marshy land of Southwark at the time surely would have helped with any such project). But whether lost or simply mythical, the truth of ‘Canute’s Canal’ remains something of a mystery. For the moment at least.

PICTURE: Rotana Ty (licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

Bookseller and philanthropist, Thomas Guy’s memory is still preserved in the London hospital which still bears his name (pictured above).

Guy was born the son of Thomas Guy, Sr, a lighterman, carpenter and coalmonger (and Anabaptist) in Southwark, in about 1644. But his father died when he was just eight-years-old and his mother Anne moved the family to Tamworth, her home town, where he was educated at the local free grammar school.

In 1660, he returned to London where he was apprenticed to a bookseller in Cheapside. Eight years later (and having lived through the Great Plague and The Great Fire), his apprenticeship completed and now admitted as a freeman to Worshipful Company of Stationers, he opened his own bookstore on the corner of Cornhill and Lombard Street in the City of London where he found success in selling illegal fine quality printed Bibles from what is now The Netherlands.

In 1660, he returned to London where he was apprenticed to a bookseller in Cheapside. Eight years later (and having lived through the Great Plague and The Great Fire), his apprenticeship completed and now admitted as a freeman to Worshipful Company of Stationers, he opened his own bookstore on the corner of Cornhill and Lombard Street in the City of London where he found success in selling illegal fine quality printed Bibles from what is now The Netherlands.

He went on to obtain a contract from Oxford University for the printing of Bibles, prayer books and other classical works – a move which saw his fortune begin to take off, so much so he apparently renamed his shop the ‘Oxford Arms’.

But Guy also became a noted investor and it was through doing so – particularly his success in investing in and then offloading shares in the booming South Sea Company (before it collapsed) – which, alongside his success as a publisher, helped to create his fortune.

He had a somewhat notorious reputation for frugality (there is a somewhat dubious story that he broke off an engagement with a maidservant following a dispute concerning some paving works she authorised without his permission) but is also known to have been a significant philanthropist.

His giving included funding upgrades to his former school in Tamworth as well the building of almshouses there in 1678. In fact, his connections with the town were still deep – he represented the town as its MP between 1675 to 1707 – he was so angry was he at his rejection in 1608 that he threatened to pull down the town hall and, later, in his will specifically deprived the inhabitants of Tamworth of use of the almshouses.

Guy had, meanwhile, refused the offer of taking up the post of Sheriff of London after he was elected, apparently because of the expense involved, and paid a fine instead.

He was appointed a governor of St Thomas’s Hospital in 1704 which he also funded the expansion of (using the money he’d made through his investment in the South Sea Company), building three new wards. Having obtained permission to build a hospital for “incurables” discharged from St Thomas’ Hospital, he began building his own hospital, Guy’s, near London Bridge in 1722.

Guy never married and died at his home in the City on 27th December, 1724. He laid in state in the Mercer’s Chapel before being buried in the crypt beneath the chapel at Guy’s Hospital (a fine monument by John Bacon now stands over the site).

He left considerable bequeathments to various charitable organisations as well as to relatives but the bulk of his estate went to his hospital – which was now roofed – so that the works could be completed. The bronze statue outside the hospital, by Scheemakers, depicts guy in his livery.

PICTURE: David Adams

The name of this City of London establishment relates directly to the trade that once existed in nearby environs – namely in sugar.

Located at 65 Cannon Street, the area to the south of the pub was once a centre of the city’s sugar refinement industry.

There were several small sugar refineries there – where raw sugar was taken and transformed into cone-shaped sugar loaves – but these were apparently destroyed when Southwark Bridge was built in the early 19th century.

The now Grade II-listed pub is said to date from the 1830s. More recently, it was part of the Charrington group before becoming one of the O’Neill’s Irish-themed pubs in the late 1990s. It became part of the Nicholson’s group a few years ago.

For more, see www.nicholsonspubs.co.uk/restaurants/london/thesugarloafcannonstreet.

PICTURE: Ewan Munro (licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0)

A 16 metre long splinter of stone sticking up in the air at the southern end of London Bridge, the Southwark Needle (its official name is actually the Southwark Gateway Needle) was erected in 1999.

A 16 metre long splinter of stone sticking up in the air at the southern end of London Bridge, the Southwark Needle (its official name is actually the Southwark Gateway Needle) was erected in 1999.

Made of Portland stone and sitting on an angle of 19.5 degrees, it was designed by Eric Parry Architects as part of the Southwark Gateway Project which also included the creation of a new tourist information centre.

There’s been much speculation about what the pointed obelisk actually represents with some believing that the sharp spike is a kind of memorial to those whose heads were placed on spikes above the gateway which once stood at the southern end of London Bridge.

It seems, however, that the subject remembered in the monument is rather more mundane – it’s a marker and apparently points across the Thames the Magnus the Martyr church which marked the start of where London Bridge was formerly located (several metres to the east of the current bridge’s location). And for those trying to figure out how the needle points to that, word is that is the line of the base of the marker which points to the start of the old bridge – not the sharp end of the obelisk.

The needle is now commonly used as a meeting point.

PICTURE: Donald Judge (licensed under CC BY 2.0)

Erected around the turn of the 19th century to celebrate Queen Victoria’s Diamond Jubilee in 1897 (some put the date of its erection at about 1897; others in about 1905), the clocktower replaced an obelisk that had previously stood in the centre of St George’s Circus in Southwark.

Erected around the turn of the 19th century to celebrate Queen Victoria’s Diamond Jubilee in 1897 (some put the date of its erection at about 1897; others in about 1905), the clocktower replaced an obelisk that had previously stood in the centre of St George’s Circus in Southwark.

The rather ornate tower was designed by architect and engineer Jan F Groll and featured four oil lamps to help light the intersection, described as the first purpose-built traffic junction in England.

It survived until the late 1930s when it was demolished after being described as a nuisance to traffic.

Meanwhile, the Robert Mylne-designed obelisk had been first erected in 1771 and marked one mile from Palace Yard, one mile 40 feet from London Bridge and one mile, 350 feet from Fleet Street (Mylne, incidentally, was the architect of the original Blackfriars Bridge).

Following its removal, it was taken to Geraldine Mary Harmsworth Park where it stood until 1998 when it was moved back to its position in St George’s Circus where it now stands. It was Grade II*-listed in 1950.

There’s a replica of the obelisk in Brookwood Cemetery – it marks the spot where bodies taken from the crypt of the Church of St George the Martyr, located in Borough High Street, in 1899 were reinterred to ease crowding.

PICTURE: Once the site of a clocktower, the obelisk has since been returned to St George’s Circus (Martin Addison/licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0/image cropped)