LondonLife – Millennium Bridge bubbles…

Located in an inlet where the River Neckinger enters the Thames just to the east of Tower Bridge, this dock has been used since the early middle ages.

This small but historic London dock is located at Bankside on the south bank of the Thames.

Read more of this content when you subscribe today.

This pub, located in Southwark, just north of Borough Market (and Southwark Cathedral), owes its name to the proximity of the river and the traditional practice of mudlarking – a word used to describe the idea of scavanging the banks of the Thames for valuables.

Mudlarking rose to prominence in the 18th and 19th centuries and the mudlarks were often children, mostly boys, who would undertake the dangerous activity of scavanging the foreshore of the tidal Thames on a daily basis in an effort to supplement the family income.

The 19th century journalist Henry Mayhew wrote about mudlarks he encountered on the river, including a nine-year-old who, dressed in nothing but trousers that had been worn away to shorts, had apparently already been about the activity for three years.

The mudlarks were after anything that could be sold for a small income – coal, ropes, bones, iron and copper nails.

The practice continues today – and has unearthed some fascinating historic finds – but anyone wanting to do so needs a permit from the Port of London Authority (and must respect rules around their finds that are of an historical nature).

The pub, meanwhile, originally dates from the mid-1700s and used to feature child mudlarks on its sign (it now has a hand holding a mudlark’s find of a coin).

It is (unsurprisingly, given the location) said to be popular with market traders and attendees.

The pub, located on Montague Close, is these days part of the Nicholson’s chain. For more, see https://www.nicholsonspubs.co.uk/restaurants/london/themudlarklondonbridge#/

London’s oldest surviving pie and mash shop is generally said to be the establishment of M Manze near Tower Bridge.

The shop was opened in 1902 by Michele Manze, who was born in Ravello, southern Italy, and has been serving their pies and mash with green liquor (a parsley sauce) and eels ever since.

Manze had arrived in London with his family when just three-years-old and settling in Bermondsey, south of the Thames, has started what was originally an ice supply business which soon started selling ice-cream. But Michele branched out into the pie and mash business.

The first shop under his name was at 87 Tower Bridge Road. It was established by Robert Cooke (of a famed family of pie and mash purveyors) in 1891 and Manze took over soon after his marriage to Cooke’s widowed daughter, Ada Poole.

Manze opened a second in Southwark Park Road in 1908. Three further shops followed – two in Poplar which were destroyed in World War II – one at Peckham High Street in 1927.

Several of his brothers including Luigi, meanwhile, opened their own pie and mash shops and so it’s said there were 14 pie, mash and eel shops bearing the Manze name by 1930.

That number has since been whittled down for various reasons and there are today there are three M Manze pie and mash shops – the Tower Bridge Road and Peckham establishments and a third which was opened in Sutton in 1998.

The Tower Bridge Road shop was damaged during World War II when the front of it was blown out.

Famous clientele have apparently included Roy Orbison, Rio Ferdinand and David Beckham and it even appeared in a music video of Elton John’s.

For more, see https://www.manze.co.uk

It’s widely reported that the first banana went on sale in London in the mid-17th century but there is evidence bananas had been in the capital well before that date.

Subscribe for full access for just £3 a month.

This district of London, which lies to the south-east of Peckham in the London Borough of Southwark, is believed to owe its name to a local tavern named, you guessed it, the Nun’s Head on the linear Nunhead Green (there’s still a pub there, called The Old Nun’s Head, in a building dating from 1905).

There may well have been actual nuns here (from which the tavern took its name) – it’s suggested that there was a nunnery here which may have been connected to the Augustinian Priory of St John the Baptist founded in the 12th century at Holywell (in what is now Shoreditch).

A local legend gets more specific. It says that when the nunnery was dissolved during the Dissolution, the Mother Superior was executed for her opposition to King Henry VIII’s policies and her head was placed in a spike on the site near the green where the inn was built.

While the use of the name for the area goes back to at least the 16th century, the area remained something of a rural idyll until the 1840s when the Nunhead Cemetery, one of the “Magnificent Seven” cemeteries of Victorian London, was laid out and the area began to urbanise.

A fireworks manufactory – Brocks Fireworks – was built here in 1868 (evidenced by the current pub, The Pyrotechnists Arms). The railway arrived in 1871.

St Antholin’s Church was built in 1877 using funds from the sale of the City of London church, St Antholin’s, Budge Row, which was demolished in 1875. St Antholin’s in Nunhead was destroyed during the Blitz and later rebuilt and renamed St Antony’s (the building is now a Pentecostal church while the Anglican parish has been united with that of St Silas).

There’s also a Dickens connection – he rented a property known as Windsor Lodge for his long-term mistress, actress Ellen Ternan, at 31 Lindon Grove and frequently visited her there (in fact, it has even been claimed that he died at the property and his body was subsequently moved to his home at Gad’s Hill to avoid a scandal).

Nunhead became part of the Metropolitan Borough of Camberwell in 1900. These days, it’s described by Foxtons real estate agency as “a quiet suburb with pretty roads and period appeal”.

London’s oldest roundabout is said to be located in Southwark at the intersection of Borough, Westminster Bridge, Waterloo, London and Blackfriars Roads.

St George’s Circus was built in 1771 (during the reign of King George III) and designed by Robert Mylne as a grand southern entrance to London with radiating roads leading to three bridges over the Thames: London Bridge, Westminster Bridge and Blackfriars Bridge.

Mylne also designed the obelisk which still stands in the centre of the circus. As well as showing the date on which it was erected, the obelisk also records distances to Palace Yard in Westminster, Fleet Street, and London Bridge. Gas lamps were placed at each corner to illuminate the intersection.

The now Grade II*-listed obelisk has a rather interesting history in itself. Having stood at the roundabout for more than a century, in about 1897 it was relocated to Geraldine Mary Harmsworth Park outside the Imperial War Museum on Lambeth Road to make way for a clocktower designed to mark Queen Victoria’s Diamond Jubilee.

The clocktower itself, however, was removed in the 1930s to help with traffic flow. It wasn’t until 1998 that the obelisk was moved back to its original site (now minus the oil lamps).

Interestingly, an Act of Parliament passed in 1812 specifies that all buildings on the intersection must be located 240 feet from the obelisk (the reason, apparently, for curved facades on some of the surrounding buildings).

• A new exhibition exploring how Impressionist and Post-Impressionist artists in late 19th-century France radically transformed the status of works on paper opens at the Royal Academy on Friday. Impressionists on Paper: Degas to Toulouse-Lautrec features around 80 works on paper by artists including Mary Cassatt, Paul Cézanne, Edgar Degas, Paul Gauguin, Eva Gonzalès, Claude Monet, Berthe Morisot, Odilon Redon, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Georges Seurat, Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec and Vincent van Gogh. Among the highlights are Degas’ Woman at a Window (1870-71), van Gogh’s The Fortifications of Paris with Houses (1887), Monet’s Cliffs at Etretat: The Needle Rock and Porte d’Aval (c1885) and Toulouse-Lautrec’s images of the urban underworld of Montmartre. The display can be seen in The Gabrielle Jungels-Winkler Galleries until 10th March. Admission charges apply. For more, see royalacademy.org.uk.

• English Heritage have unveiled their final Blue Plaque for 2023 and it celebrates two of the most influential painters of the early-to-mid 20th century, Vanessa Bell and Duncan Grant. The plaque was unveiled at number 46 Gordon Square in Bloomsbury, from where the Bloomsbury Group – of which Bell and Grant were leading members – drew its name. Bell first lived at number 46 with her siblings, including Virginia Stephen (later Woolf), and, in 1914, Grant moved in with Vanessa and her husband, Clive Bell. Paintings the pair made at number 46 include Grant’s Interior at Gordon Square (c1915) and Bell’s Apples: 46 Gordon Square (c1909-10), a still-recognisable view from the drawing-room balcony to the square. For more on the English Heritage Blue Plaques scheme, head to www.english-heritage.org.uk/visit/blue-plaques/.

• The history of Burnham Beeches has been brought to life with a new augmented reality app. The app allows users to superimpose periods of Burnham Beeches’ history – from the Iron Age, Middle Ages and World War II – over what they see when visiting the site and incorporates sounds from selected era as well. It can be accessed via a QR code which is being published on signs at Burnham Beeches. Burnham Beeches, located near the village of Burnham in Buckinghamshire, was acquired by the City of London in 1880 when the area was threatened by development and is managed as a free open space. For more, head here.

• The work of 30 young artists celebrating African community and culture is being showcased on billboards across the city in conjunction with Tate Modern’s current exhibition, A World in Common. The photographs have been selected following a call from the Tate Collective for 16-to-25-year-olds to submit images responding to the exhibition. More than 100 entries were submitted by young people based across the UK and beyond and Londoners will be able to view the 30 shortlisted works on billboards in Haringey, Lambeth, Southwark and Tower Hamlets over the next two weeks.

Send all items to exploringlondon@gmail.com.

A stretch of the River Thames which spans the area from London Bridge to below Limehouse, the Pool of London was the highest part of the river navigable by tall-masted ships (thanks to the them not being able to pass under London Bridge).

The term originally referred to the stretch of the river at Billingsgate in the City of London which was where all imports had to be delivered for inspection by customs officers (hence these wharves were given the name ‘legal quays’).

But as trade expanded and reached its peak in the 18th and 19th centuries, so too did the stretch referred to as the “Pool of London”. It came to be divided into two sections – the Upper Pool, which stretches from London Bridge to Cherry Garden Pier in Bermondsey (and is bisected by Tower Bridge), and the Lower Pool, which stretched from the latter pier to Limekiln Creek.

The Upper Pool’s north bank includes the Tower of London, the old Billingsgate Market and the entrance to St Katharine’s Dock while the south bank features Hay’s Wharf and the HMS Belfast. The Lower Pool’s north bank includes the entrance to Limehouse Cut as well as Regent’s Canal and Execution Docks while below it runs the Thames and Rotherhithe Tunnels.

An inhabitant of Roman Londinium some 1,600 years ago, a wealthy Roman woman was laid to rest in a stone sarcophagus in what is now Southwark.

Her rest was not uninterrupted. At some point – reported as during the 16th century – thieves broke into her coffin, allowing earth to pour in. The sarcophagus was then reburied and and lay undisturbed until June, 2017, when it was found at a site on Harper Road by archaeologists exploring the property prior to the construction of a new development.

Subsequent analysis found that almost complete skeleton of a woman as well as some bones belonging to an infant (although it remains unclear if they were buried together). Along with the bones was a tiny fragment of gold – possibly belonging to an earring or necklace – and a small stone intaglio, which would have been set into a ring, and which is carved with a figure of a satyr.

The burial, which took place at the junction of Swan Street and Harper Road, is estimated to have taken place between 86 and 328 AD and the woman was believed to be aged around 30 when she died.

It’s clear from the 2.5 tonne sarcophagus that the woman was of high status – most Londoners of this area were either cremated or buried in wooden coffins. The sarcophagus was only one of three found in London in the past three decades.

• A series of free art trails featuring globe sculptures that aim to increase understanding of the Transatlantic slave trade and its impacts have gone on show in several parts of central London. A national art project which spans seven UK cities, The World Reimagined is designed to bring to life the reality and impact of the slave trade in a bid to help make racial justice a reality. Among the artists involved in London are the project’s founding artist British-Nigerian Yinka Shonibare (who also chose the form of the sculptures), Nicola Green and Winston Branch and each has created a work responding to themes ranging from ‘Mother Africa’ and ‘The Reality of Being Enslaved’ to ‘Still We Rise’ and ‘Expanding Soul’. There are four trails in London, including in the City in London, Camden-Westminster, Hackney-Newham and Southwark-Lambeth. More than 100 artists are involved in the project overall. For more including details on where to find the trails, see www.theworldreimagined.org.

• Dadabhai Naoroji, an Indian Nationalist and the first Indian to win a popular election to Parliament in the UK, has been honoured with an English Heritage Blue Plaque at his former home in Penge. Known as the “grand old man of India” and described in his Times obituary as “the father of Indian Nationalism” following his death in 1917, Naoroji made seven trips to England and spent over three decades of his life in London, including at the red-bricked semi-detached house in Penge, south London, that was his home around the turn of the twentieth century and where the plaque is located. The plaque was unveiled last week ahead of the 75th anniversary celebrations of India’s independence. For more, see www.english-heritage.org.uk/visit/blue-plaques/.

Send all items for inclusion to exploringlondon@gmail.com

Think of fire in relation to London and the events of 1666 no doubt spring to mind. But London has had several other large fires in its history (with a much higher loss of life), including during the reign of King John in July, 1212.

The fire started in Southwark around 10th July and the blaze destroyed most of the buildings lining Borough High Street along with the church of St Mary Overie (also known as Our Lady of the Canons and now the site of Southwark Cathedral) before reaching London Bridge.

The wind carried embers across the river and ignited buildings on the northern end before the fire spread into the City of London itself (building on the bridge had been authorised by King John so the rents could be used to help pay for the bridge’s maintenance).

Many people died on the bridge after they – and those making their way south across the bridge to aid people in Southwark (or perhaps just to gawk) – were caught between the fires at either end, with some having apparently drowned after jumping off the bridge into the Thames (indeed, it’s said that some of the crews of boats sent to rescue them ended up drowning themselves after the vessels were overwhelmed).

Antiquarian John Stow, writing in the early 17th century, stated that more than 3,000 people died in the fire – leading some later writers to describe the disaster as “arguably the greatest tragedy London has ever seen”.

But many believe this figure is far too high for a population then estimated at some 50,000. The oldest surviving account of the fire – Liber de Antiquis Legibus (“Book of Ancient Laws”) which was written in 1274 and mentions the burning of St Mary Overie and the bridge, as well as the Chapel of St Thomas á Becket built upon it – doesn’t mention a death toll.

London Bridge itself survived the fire thanks to its recent stone construction but for some years afterward it was only partly usable. King John then raised additional taxes to help rebuild destroyed structures while the City’s first mayor, Henry Fitz Ailwyn, subsequently apparently joined with other officials in creating some regulations surrounding construction with fire safety in mind.

The cause of the fire remains unknown.

This garden can be found on the roof of the Queen Elizabeth Hall at the Southbank Centre.

The 1,200 square metre garden, which was created in 2011 as part of the 60th anniversary of the 1951 Festival of Britain celebrations, was developed in partnership with the Eden Project.

It is maintained by volunteers from Grounded Ecotherapy, a group which offers people dealing with issues like homelessness and addiction help through horticulture.

The Garden features more than 200 wild native plants as well as a lawn, paths and paving – and stunning views across the river. There’s also a cafe and bar.

WHERE: Queen Elizabeth hall Roof Garden (nearest Tube stations are Waterloo and Embankment); WHEN: Wednesday to Sunday from noon; COST: Free; WEBSITE: www.southbankcentre.co.uk/visit/outdoor/queen-elizabeth-hall-roof-garden-cafe-bar.

This small walled garden, located in Southwark, for centuries served as a burial site for the poor of the area nd by the time of its closing in 1853, was the location of some 15,000 burials.

The graveyard is said to have started life as an unconsecrated burial site for ‘Winchester Geese’, sex workers in the medieval period who were licensed to work in the brothels of the Liberty of the Clink by the Bishop of Winchester.

Excavations carried out in the 1990s confirmed a crowded graveyard was on the site.

While the site had been neglected for years following its closure, in 1996 local writer John Constable and a group he co-founded, the Friends of Crossbones, began a campaign to transform Crossbones into a garden of remembrance – something which has happened thanks to their efforts and those of the Bankside Open Spaces Trust and others.

The garden provides a contemplative space for people to pay their respects to what have become known as the “outcast dead”.

A plaque, funded by Southwark Council, was installed on the gates in 2006 which records the history of the site and the efforts to create a memorial shrine.

WHERE: Crossbones Graveyard, Redcross Way, Southwark (nearest Tube stations are London Bridge and Borough); WHEN: Wednesdays, Thursdays and Fridays 12 to 2pm; COST: Free; WEBSITE: www.bost.org.uk/crossbones-graveyard.

Long thought to have been London’s oldest public statue (and certainly the oldest of a monarch), this statue of Anglo-Saxon King Alfred the Great stands in a quiet location in Trinity Church Square in Southwark.

The statue – which depicts the bearded king robed and wearing a crown – was believed to have medieval origins with some suggesting it was among those which north face of Westminster Hall since the 14th century and were removed by Sir John Soane in 1825.

But recent conservation work has shown that half of the statue is actually much older. In fact, it’s believed that the lower half of the figure was recycled from a statue dedicated to the Roman goddess Minerva and is typical of the sort of work dating from the mid-second century.

Measurements of the leg of the lower half indicate the older statue stood some three metres in height, according to the Heritage of London Trust. It is made of Bath Stone and was likely carved by a stone worker located on the continent. It probably came from a temple.

The top half, meanwhile is made of Coade stone and, given that wasn’t invented by Eleanor Coade until around 1770, the creation of the statue as it appears today is obviously much later than was originally suspected which may give credence to theory that it was one of a pair – the other representing Edward the Black Prince – made for the garden of Carlton House in the late 18th century.

Putting the two parts of the statue together would have required some specialised skills.

The Grade II-listed statue has stood in the square since at least 1826. Much about who created it still remains a mystery. The fact it incorporates a much older statue means the question of whether it is in fact London’s oldest outdoor public statue remains a matter of some debate.

In honour of Queen Elizabeth II’s Platinum Jubilee, we have a new series looking at 10 lesser known statues of previous monarchs in London.

We kick off with not one, but actually two, statues of King Edward VI, the son of King Henry VIII and his third queen, Jane Seymour, can be found at St Thomas Hospital in Southwark.

Both of the statues were commissioned to commemorate the king’s re-founding of the hospital – which had been first founded in the 12th century and had been closed in 1540 as part of the Dissolution – in 1551 and which saw the complete rebuilding of the hospital under the stewardship of the hospital’s President, Sir Robert Clayton.

The oldest of the statues, now located outside the north entrance to the hospital’s North Wing on Lambeth Palace Road, was designed by Nathaniel Hanwell and carved from Purbeck limestone by Thomas Cartwright in 1682.

It originally was part of a group – the King standing at the centre holding his raised sceptre surrounded by four figures which were innovative in that they depicted patients of the time – which adorned the gateway to the hospital on Borough High Street.

It was moved when the gate was widened in around 1720 and subsequently occupied several different positions – including spending some time in storage – before eventually, without the surrounding figures, being moved to its current position in 1976. It was designated a Grade II* monument in 1979.

The second of the two statues is a bronze figure in period dress which was created by sculptor Peter Scheemakers in 1737.

It can now be found inside the hospital’s North Wing, having been moved there last century, and like its counterpart, was designated a Grade II* monument in 1979.

The inscription on the front of the plinth describes the King as “a most excellent prince of exemplary piety and wisdom above his years, the glory and ornament of his age and most munificent founder of this hospital” and adds that the statue was erected at the expense of Charles Joye, Treasurer of the hospital.

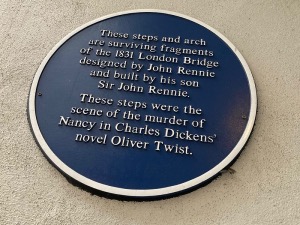

We close our series of historic London stairs with a stairway that has raised its share of controversy in recent years, largely due to the plaques associated with it.

The steps, which are located in Southwark at the southern end of London Bridge and which lead down to Montague Close, are a remnant of the John Rennie-designed London Bridge which was completed in 1831 and which was replaced in the mid-20th century (and which was sold off and relocated to Lake Havasu in the US).

The controversy arises through the plaques associated with the steps which state that the steps where the scene of the murder of Nancy in Charles Dickens’ Oliver Twist. There’s a couple of problems with that claim.

The first is that Nancy wasn’t murdered here in the book – it is in their lodgings that Bill Sikes kills Nancy believing she has betrayed him. The confusion probably comes about because the musical Oliver! did set Nancy’s murder on the steps.

The bridge does, however, play a role in the book and have a connection to Nancy and its probably due to this connection that it has its name, Nancy’s Steps.

Because it was on steps located here – “on the Surrey bank, and on the same side of the bridge as Saint Saviour’s Church [now known as Southwark Cathedral]” that Nancy talks to Oliver’s benefactors while Noah Claypole eavesdropped on the conversation (which leads him reporting back to Sikes and eventually to her murder).

The second error made in the plaque is that Rennie’s bridge (and hence the steps) was completed in 1831 and with Oliver Twist published in serial form just a few years later can’t be the “ancient” bridge referred to in the text. The reference can only relate to the medieval bridge which occupied the site for hundreds of years until it was demolished following the completion of Rennie’s bridge.

Southwark Bridge celebrated its 100th birthday earlier this month so we thought it a good time to have a quick look at the bridge’s history.

The bridge was a replacement for an earlier three-arch iron bridge built by John Rennie which had opened in 1819.

Known by the nickname, the “Iron Bridge”, it was mentioned in Charles Dickens’ Our Mutual Friend and Little Dorrit. But the bridge had problems – its narrow approaches and steep gradient led it to become labelled “the curse of the carman [cart drivers] and the ruin of his horses”.

Increasing traffic meant a replacement became necessary and a new bridge, which featured five arches and was made of steel, was designed by architect Sir Ernest George and engineer Sir Basil Mott.

Work on the new bridge – which was to cost £375,000 and was paid for by the City of London Corporation’s Bridge House Estates which was originally founded in 1097 to maintain London Bridge and expanded to care for others – began in 1913 but its completion was delayed thanks to the outbreak of World War I.

The 800 foot long bridge was finally officially opened on 6th June, 1921, by King George V who used a golden key to open its gates. He and Queen Mary then rode over the bridge in a carriage.

The bridge, now Grade II-listed, was significantly damaged in a 1941 air raid and was temporarily repaired before it was properly restored in 1955. More recently, the bridge was given a facelift in 2011 when £2.5 million was spent cleaning and repainting the metalwork in its original colours – yellow and ‘Southwark Green’.

The current bridge has appeared in numerous films including 1964’s Mary Poppins and, in more recent times, 2007’s Harry Potter and the Order of the Phoenix.