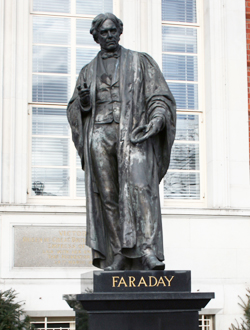

A towering figure of the scientific world, Faraday made significant contributions to understanding the fields of electromagnetism and electrochemistry and was a key figure at the Royal Institution of Great Britain in the 19th century.

Faraday was born in Newington Butts in Surrey (now in south London, part of the Borough of Southwark) on 22nd September, 1791, and, coming from a poorer family, received only a basic education before, at the age of 14, he started an apprenticeship as a bookbinder.

Faraday was born in Newington Butts in Surrey (now in south London, part of the Borough of Southwark) on 22nd September, 1791, and, coming from a poorer family, received only a basic education before, at the age of 14, he started an apprenticeship as a bookbinder.

The job proved, however, to be something of a godsend, for Faraday was able to read a wide range of books and educate himself – it was during this time that he began what was a lifelong fascination with science.

In 1812 at the end of his apprenticeship, he attended a series of lectures at the Royal Institution by the chemist Sir Humphry Davy. Subsequently asking Sir Humphry for a job, he eventually was granted one the following year – in 1813 – when Sir Humphry appointed him to the post of chemical assistant in the laboratory at the RA (the job came with accommodation).

Faraday’s ‘apprenticeship’ under Davy – which included an 18 month long tour of Europe in his company – was critical to his future success and from 1820 onward – having now settled at the RA, he made numerous contributions to the field of chemistry – including discovering benzene, inventing the earliest form of Bunsen burner and popularising terms like ‘cathode’ and ‘ion’.

But it was in physics that he made his biggest impact, making discoveries that would, according to the Encyclopaedia Britannica, “revolutionise” our understanding of the field.

Faraday, who married Sarah Barnard, the daughter of a silversmith, in 1821 and was thereafter an active member of the Sandemanian Church to which she belonged, published his ground-breaking first work on electromagnetism in 1821 (it concerned electromagnetic rotation, the principle behind the electric motor). His discovery of electromagnetic induction (the principle behind the electric transformer and generator) was made in 1831 and he is credited with having constructed the first electric motor and the first ‘dynamo’ or electric generator.

Faraday, who would continue his work on ideas concerning electricity over the next decade, was awarded numerous scientific appointments during his life including having been made a member of the Royal Society in 1924, the first Fullerian Professor of Chemistry at the Royal Institution, from 1833 until his death, scientific advisor to lighthouse authority for England and Wales – Trinity House, a post he held between 1836 and 1865, and Professor of Chemistry at the Royal Military Academy in Woolwich, a post her held between 1830 and 1851.

He also, in 1825, founded the Royal Institution’s famous “Friday Evening Discourses” and the “Christmas Lectures”, both of which continue to this day. Over the ensuring years, he himself gave many lectures, firmly establishing himself as the outstanding scientific lecturer of the day.

Faraday’s health deteriorated in the early 1840s and his research output lessened although by 1845 he was able to return to active research and continued working until the mid 1850s when his mind began to fail. He died on 25th August, 1867, at Hampton Court where he had been granted, thanks to Prince Albert, grace and favour lodgings by Queen Victoria (she’d also apparently offered him a knighthood which he’d rejected). He was buried in Highgate Cemetery.

Faraday is commemorated with numerous memorials around London including a bronze statue at Savoy Place outside the Institution of Engineering and Technology, a Blue Plaque on the Marylebone property where he was an apprentice bookbinder (48 Blandford Street), and a rather unusual box-shaped metallic brutalist memorial at Elephant and Castle. And, of course, there’s a famous marble statue of Faraday by John Henry Foley inside the RI (as might be expected, the RI, home of The Faraday Museum, have a host of information about Faraday including a ‘Faraday Walk’ through London’s streets).

PICTURE: Adambro/Wikimedia Commons/CC BY 3.0

In 1849, to capitalise on trade to the upcoming Great Exhibition in Hyde Park in 1851, he took over a small shop on the site of the current store – initially with just two assistants and a messenger boy. In 1861 his son, the similarly-named Charles Digby Harrods, took over the business and by 1880, the store was employing more than 100 people offering customers everything from medicines and perfumes to clothing and food and already attracting the wealthy customers it would become known for.

In 1849, to capitalise on trade to the upcoming Great Exhibition in Hyde Park in 1851, he took over a small shop on the site of the current store – initially with just two assistants and a messenger boy. In 1861 his son, the similarly-named Charles Digby Harrods, took over the business and by 1880, the store was employing more than 100 people offering customers everything from medicines and perfumes to clothing and food and already attracting the wealthy customers it would become known for.

A detailed picture of the inhabitants of Roman London, known as Londinium, has been created for the first time, the Museum of London announced this week. Detailed analysis of the DNA of four skeletons has revealed a culturally diverse population. The examined skeletons include that of a Roman woman (pictured left), likely to have been born in Britain with northern European ancestry, found buried with high status grave goods at Harper Road, Southwark, in 1979, and another of a man, whose DNA revealed connections to Eastern Europe and the Near East, who was found at London Wall in 1989 with injuries to his skull which suggest he may have been killed in the nearby amphitheatre before his head was dumped in a pit. The other two skeletons examined were found to be that of a blue-eyed teenaged girl found at Lant Street, Southwark, in 2003, believed to have been born in north Africa, whose ancestors lived in south-eastern Europe and west Eurasia, and that of an older man found at Mansell Street who was born in London and whose ancestry had links to Europe and north Africa. The examination – the first multi-disciplinary study of the inhabitants of a Roman city anywhere in the empire – also revealed that all four suffered from gum disease. Caroline McDonald, senior curator at the museum, said that while it has always been understood Roman London was a culturally diverse place, science was now “giving us certainty”. “People born in Londinium lived alongside people from across the Roman Empire exchanging ideas and cultures, much like the London we know today.” The four skeletons will form the basis of a new free display, Written in Bone, opening at the Museum of London on Friday. PICTURE: © Museum of London

A detailed picture of the inhabitants of Roman London, known as Londinium, has been created for the first time, the Museum of London announced this week. Detailed analysis of the DNA of four skeletons has revealed a culturally diverse population. The examined skeletons include that of a Roman woman (pictured left), likely to have been born in Britain with northern European ancestry, found buried with high status grave goods at Harper Road, Southwark, in 1979, and another of a man, whose DNA revealed connections to Eastern Europe and the Near East, who was found at London Wall in 1989 with injuries to his skull which suggest he may have been killed in the nearby amphitheatre before his head was dumped in a pit. The other two skeletons examined were found to be that of a blue-eyed teenaged girl found at Lant Street, Southwark, in 2003, believed to have been born in north Africa, whose ancestors lived in south-eastern Europe and west Eurasia, and that of an older man found at Mansell Street who was born in London and whose ancestry had links to Europe and north Africa. The examination – the first multi-disciplinary study of the inhabitants of a Roman city anywhere in the empire – also revealed that all four suffered from gum disease. Caroline McDonald, senior curator at the museum, said that while it has always been understood Roman London was a culturally diverse place, science was now “giving us certainty”. “People born in Londinium lived alongside people from across the Roman Empire exchanging ideas and cultures, much like the London we know today.” The four skeletons will form the basis of a new free display, Written in Bone, opening at the Museum of London on Friday. PICTURE: © Museum of London Little is known of Jack Cade until the former soldier from Kent led an uprising against the rule of King Henry VI during the Hundred Years War with France. And London was a key site of fighting during the uprising.

Little is known of Jack Cade until the former soldier from Kent led an uprising against the rule of King Henry VI during the Hundred Years War with France. And London was a key site of fighting during the uprising.