This year marks the 160th anniversary of the transfer of the care of the Royal Parks to the government (meaning the public was freely able to enjoy access for the first time). To celebrate, over the next weeks we’ll be taking a look at the history of each of them. First up is the 142 hectare Hyde Park, perhaps the most famous of all eight Royal Parks.

This year marks the 160th anniversary of the transfer of the care of the Royal Parks to the government (meaning the public was freely able to enjoy access for the first time). To celebrate, over the next weeks we’ll be taking a look at the history of each of them. First up is the 142 hectare Hyde Park, perhaps the most famous of all eight Royal Parks.

Formerly owned by Westminster Abbey, King Henry VIII seized the land in 1536 for use as a private hunting ground. He had it enclosed with fences and the Westbourne Stream, which ran through the park – it now runs underground – dammed.

It remained the king and queen’s private domain (Queen Elizabeth I is known to have reviewed troops there) until King James I appointed a ranger to look after the park and permitted limited access to certain members of the nobility in the early 17th century.

The park’s landscaping remained largely unaltered until the accession of King Charles I – he created what is known as the ‘ring’ – a circular track where members of the royal court could drive their carriages. In 1637, he also opened the park to the public (less than 30 years later, in 1665, it proved a popular place for campers fleeing the Great Plague in London).

During the ensuring Civil War, the Parliamentarians created forts in the park to help defend the city against the Royalists – some evidence of their work still remains in the raised bank next to Park Lane.

After King William III and Queen Mary II moved their court to Kensington Palace (formerly Nottingham House) in the late 1600s, they had 300 oil lamps installed along what we know as “Rotten Row’ – the first artificially lit road in the country – to enable them and their court to travel safely between the palace and Westminster.

The natural looking Serpentine – the great, 11.34 hectare, lake in the middle of Hyde Park (pictured) – was created in the 1730s on the orders of Queen Caroline, wife of King George II, as part of extensive work she had carried out there. It was Queen Caroline who also divided off what we now know as Kensington Gardens from Hyde Park, separating the two with a ha-ha (a ditch).

The next major changes occurred in the 1820s when King George IV employed architect and garden designer Decimus Burton to create the monumental park entrance at Hyde Park Corner – the screen still remains in its original position while Wellington Arch was moved from a parallel position to where it now stands (see our previous posts for more on that). Burton also designed a new railing fence and several lodges and gates for the park. A bridge across the Serpentine, meanwhile, was built at about the same time along with a new road, West Carriage Drive, formally separating Hyde Park and Kensington Gardens.

While the basic layout of the park has been largely unchanged since, there have been some additions – among them, the establishment in 1872 of Speaker’s Corner as a place to speak your mind in the north-east corner of the park (near Marble Arch), the creation in 1930 of the Lido for bathing in warm weather, and, more recently, the building of the Diana, Princess of Wales’ Memorial Fountain (unveiled in 2004), and the 7 July Memorial (unveiled in July 2009).

Other sculptures in the park include Isis (designed by Simon Gudgeon, located on the south side of the Serpentine), the Boy and Dolphin Fountain (designed by Alexander Munro, it stands in the Rose Garden), and a monumental statue of Achilles, a memorial to the Duke of Wellington designed by Richard Westmacott, near Park Lane. There are also memorials to the Holocaust, Queen Caroline, and the Cavalry as well as a Norwegian War Memorial and a mosaic marking the site of the Reformer’s Tree (the tree was burnt down during the Reform League Riots of 1866).

The park has been integral part of any national celebrations for centuries – in 1814 a fireworks display there marked the end of the Napoleonic Wars, the Great Exhibition – with the vast Crystal Palace – was held there in 1851 and in 1977 a Silver Jubilee Exhibition was held marking Queen Elizabeth II’s 25 year reign. Cannons are fire there on June 2nd to mark the Queen Elizabeth II’s coronation and on 10th June for the Duke of Edinburgh’s birthday.

Facilities these days include rowing and pedal boats, tennis courts, deck chairs, a restaurant and cafe (the latter based in the Lido) and, of course, some Boris bikes. There is a heritage walk through the park which can be downloaded from the Royal Parks website.

WHERE: Hyde Park (nearest tube stations are that of Marble Arch, Hyde Park Corner, Lancaster Gate, Knightsbridge and South Kensington); WHEN: 5am to midnight; COST: Free; WEBSITE: www.royalparks.gov.uk/Hyde-Park.aspx?page=main

PICTURE: Courtesy of Royal Parks. © Indusfoto Ltd

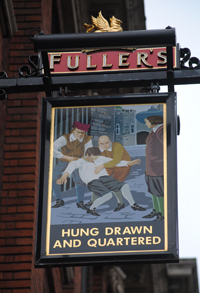

The rather grisly name of this pub (and there’s some debate over whether hanged or hung is grammatically correct) relates to its location close by the former public execution ground of Tower Hill.

The rather grisly name of this pub (and there’s some debate over whether hanged or hung is grammatically correct) relates to its location close by the former public execution ground of Tower Hill. Some of the names of those executed here are recorded on a memorial at the site – everyone from Simon Sudbury, the Archbishop of Canterbury who was beheaded here by an angry mob in 1381, through to Sir Thomas More in 1535 (gracious King Henry VIII commuted his sentence from being hung, drawn and quartered to mere beheading), and Simon Fraser, the 11th Lord Lovat, a Jacobite arrested after the Battle of Culloden and the last man to be executed here when his head was lopped off in 1747.

Some of the names of those executed here are recorded on a memorial at the site – everyone from Simon Sudbury, the Archbishop of Canterbury who was beheaded here by an angry mob in 1381, through to Sir Thomas More in 1535 (gracious King Henry VIII commuted his sentence from being hung, drawn and quartered to mere beheading), and Simon Fraser, the 11th Lord Lovat, a Jacobite arrested after the Battle of Culloden and the last man to be executed here when his head was lopped off in 1747.