Little is known of Jack Cade until the former soldier from Kent led an uprising against the rule of King Henry VI during the Hundred Years War with France. And London was a key site of fighting during the uprising.

Little is known of Jack Cade until the former soldier from Kent led an uprising against the rule of King Henry VI during the Hundred Years War with France. And London was a key site of fighting during the uprising.

Cade, who adopted the name John Mortimer and who some claimed to have been a relative of Richard, Duke of York, was said to have been a veteran of the war who led rebels protesting against the king’s rule amid the general state of disorder affecting England at the time which saw such abuses as lands being illegally seized and a lack of confidence in courts to rule fairly. There was also some discontent over the loss of lands of Normandy.

While many of the rebels were peasants, the rebellion – which rose in late May or early June, 1450 – was also supported by nobles and churchmen who were protesting what they saw as poor governance.

Led by Cade, who also attracted the title ‘Captain of Kent’, were camped on Blackheath in what is now the city’s south-east by mid-June and there apparently presented an embassy from the king with a list of grievances.

Thomas, Lord Scales – authorised by the king to raise troops, subsequently marched out to Blackheath but Cade and his rebels retreated into the forests of Kent and managed to lure the royal troops into an ambush.

Cade and the rebels returned to Blackheath while back in London the Royal soldiers turned mutinous, angered over the defeat. They were disbanded to protect the City and the king retired to Kenilworth Castle, effectively abandoning London to the rebels (despite the offer of the Lord Mayor and aldermen to resist the rebels).

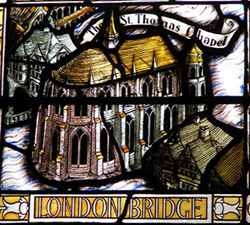

Cade then marched on London itself, reaching Southwark on 2nd July (apparently using the now vanished White Hart Inn as his HQ). He forced his way over London Bridge the next day, cutting the drawbridge ropes personally with his sword to ensure it couldn’t be raised again

Such was the support the rebels had in London, that resistance was initially minimal. Following his entry to London, Cade struck the famous London Stone (pictured above – for more on it, see our earlier post here) with his sword, declaring “Mortimer” was now lord of the city.

While initially under tight control, Cade gradually lost control of many of his followers who turned to looting. Meanwhile, to head off an attack on the Tower of London – where Lord Scales had retreated – he handed over the hated Lord Treasurer, James Fiennes, Lord Saye, and his son-in-law William Crowmer, Under Sheriff of Kent (they had apparently been imprisoned in the Tower by the King for their own protection such as their unpopularity). Both were beheaded – Fiennes at Cheapside, Crowmer at Mile End – and their heads placed on poles on London Bridge.

The king’s supporters in the Tower had regrouped by early July and, with the rebels, while initially welcomed by many, now clearly having outstayed their welcome, they and city militias drove the rebels from the streets and had taken back the northern half of London Bridge (another bloody battle over the bridge) when William of Waynflete, Bishop of Winchester, arrived with promises of pardon for the rebels on behalf of the Lord Chancellor and Archbishop of Canterbury, John Kemp.

His forced much reduced, Cade – a pardon in his pocket under Mortimer’s name only – moved back into Kent and continued to cause trouble. He was, however, captured by the new Sheriff of Kent, Alexander Iden, on 12th July, – one version says this took place near Heathfield in Sussex at a hamlet now known as Cade Street. In any event, Cade was mortally wounded during the struggle and died en route to London.

His corpse, however, completed the journey and Cade was hanged, drawn and quartered and his head placed atop a pole on London Bridge.

While the rebel ringleaders were later captured and killed, in the most part King Henry VI honoured the pardons he had granted.

The story of Cade’s rebellion features in William Shakespeare’s play, King Henry the Sixth.

Little is known of Jack Cade until the former soldier from Kent led an uprising against the rule of King Henry VI during the Hundred Years War with France. And London was a key site of fighting during the uprising.

Little is known of Jack Cade until the former soldier from Kent led an uprising against the rule of King Henry VI during the Hundred Years War with France. And London was a key site of fighting during the uprising.