The HMS Belfast has marked 45 years since it sailed up the River Thames to its current mooring site off The Queen’s Walk, just to the west of Tower Bridge. The ship, which is Europe’s only surviving World War II cruiser and which, as well as taking part in that conflict, also saw action in the Korean War, opened to the public in 1971. More than nine million people have since visited the ship which features nine decks, all of which are open to sightseers. For more on the ship, see www.iwm.org.uk/visits/hms-belfast.

World War II

10 notable blue plaques of London – 6. A blue plaque for a deadly bomb…

Not all of the plaques in the English Heritage blue plaques scheme commemorate people, some also commemorate places and events – the saddest of which is no doubt the landing of the first deadly V1 flying bomb on London during World War II.

Not all of the plaques in the English Heritage blue plaques scheme commemorate people, some also commemorate places and events – the saddest of which is no doubt the landing of the first deadly V1 flying bomb on London during World War II.

Located in Bow in the East End is a plaque commemorating the site where the first flying bomb fell on London on 13th June, 1944, a week after D-Day and several months since the last bombs had fallen on London in what was known as the “mini-blitz”.

Carrying some 850 kilograms of high explosive, the unmanned, fast-moving bomb dived to the ground at about 4.25am on the morning of the 13th, badly damaging the railway bridge and track, destroying houses and, sadly, killing six people.

It was to be the start of a new bombing offensive which would eventually see around 2,500 of the V1 flying bombs reach London between June, 1944, and March, 1945.

They were responsible for killing more than 6,000 people and injuring almost 18,000 and were followed by the even more advanced V2 long range rockets – the world’s first ballistic missiles – in September, 1944. These were responsible for another 2,754 deaths in London before the war’s end.

The current plaque on the railway bridge in Grove Road was erected in 1998 by English Heritage and replaced one which was erected by the Greater London Council in 1985 and subsequently stolen.

PICTURE: Spudgun67/CC BY-SA 4.0

A Moment in London’s history…The ‘longest night’…

It was 75 years ago this year – on the night of 10th/11th May, 1941 – that the German Luftwaffe launched an unprecedented attacked on London, an event that has since become known as the ‘Longest Night’ (it’s also been referred to as ‘The Hardest Night’).

It was 75 years ago this year – on the night of 10th/11th May, 1941 – that the German Luftwaffe launched an unprecedented attacked on London, an event that has since become known as the ‘Longest Night’ (it’s also been referred to as ‘The Hardest Night’).

Air raid sirens echoed across the city as the first bombs fells at about 11pm and by the following morning, some 1,436 Londoners had been killed and more than that number injured while more than 11,000 houses had been destroyed along and landmark buildings including the Palace of Westminster (the Commons Chamber was entirely destroyed and the roof of Westminster Hall was set alight), Waterloo Station, the British Museum and the Old Bailey were, in some cases substantially, damaged.

The Royal Air Force Museum records that some 571 sorties were flown by German air crews over the course of the night and morning, dropping 711 tons of high explosive bombs and more than 86,000 incendiaries. The planes were helped in their mission – ordered in retaliation for RAF bombings of German cities – by the full moon reflecting off the river below.

The London Fire Brigade recorded more than 2,100 fires in the city and together these caused more than 700 acres of the urban environment, more than double that of the Great Fire of London in 1666 (the costs of the destruction were also estimated at more than double that of the Great Fire – some £20 million).

Fighter Command sent some 326 aircraft into the fight that night, not all of them over London, and, according to the RAF Museum, the Luftwaffe officially lost 12 aircraft (although others put the figure at more than 30).

By the time the all-clear siren sounded just before 6am on 11th May, it was clear the raid – which turned out to be the last major raid of The Blitz – had been the most damaging ever undertaken upon the city.

Along with the landmarks mentioned above, other prominent buildings which suffered in the attack include Westminster Abbey, St Clement Danes (the official chapel of the Royal Air Force, it was rebuilt but still bears the scars of the attack), and the Queen’s Hall.

Pictured above is a statue of firefighters in action in London during the Blitz, taken from the National Firefighters Memorial near St Paul’s Cathedral – for more on that, see our earlier post here.

For more on The Longest Night, see Gavin Mortimer’s The Longest Night: Voices from the London Blitz: The Worst Night of the London Blitz.

LondonLife – Celebrating International Women’s Day…

It’s International Women’s Day, so we’re celebrating by remembering two heroic women immortalised in statues in central London. Above is Edith Cavell, a British nurse who was trapped in Brussels by advancing German armies in 1914 and then subsequently arrested for aiding French and British soldiers to escape before being executed by firing squad on 12th October, 1915 – an event widely condemned around the world. The marble statue, located in St Martin’s Place at the intersection of Charing Cross Road and St Martin’s Lane, is by George Frampton and was erected in 1920. Below, meanwhile, is a bust of Violette Szabo which tops a memorial to the Special Operations Executive (SOE). Szabo, who was posthumously awarded the George Cross and the Croix de Guerre after she was captured and eventually executed by the German Army in early 1945, was among 117 SOE agents who did not return from their missions to France. Located on Albert Embankment, the statue – which is the work of Karen Newman – was unveiled in 2009.

10 London ‘battlefields’ – 10. The Battle of London…

The final in our series looking at London ‘battlefields’, this week we take a look at the so-called Battle of London, the air war fought over London during World War II which, along with the bombing of other British cities, is best known by the phrase The Blitz (it forms part of the greater Battle of Britain).

Taking place from the afternoon of 7th September, 1940, until May, 1941, the Blitz saw London sustain repeated attacks from the German Luftwaffe, most notably between 7th September and mid November when the city was bombed on every night bar one.

Taking place from the afternoon of 7th September, 1940, until May, 1941, the Blitz saw London sustain repeated attacks from the German Luftwaffe, most notably between 7th September and mid November when the city was bombed on every night bar one.

The night of 7th September, the first night of the Blitz (a short form of ‘Blitzkrieg’ – German for ‘lightning war’), was among the worst – with more than 450 killed and 1,300 injured as wave after wave of bombers attacked the city. Another 412 were killed the following night.

One of the most notorious raids took place on 29th December when incendiary bombs dropped on the City of London starting what has been called the Second Great Fire of London. Around a third of the city was destroyed, including more than 30 guild halls and 19 churches, 16 which had been rebuilt by Sir Christopher Wren in the aftermath of the Great Fire of London in 1666.

The city was only attacked sporadically in the early months of 1941 but the night of the last major raid of the Blitz – that of 10th May, a night subsequently known as The Longest Night – saw the highest casualties of any night with almost 1,500 people reportedly killed.

The Blitz killed almost 30,000 civilian in London, and destroyed more than a million homes with the worst hit districts poorer areas like the East End.

The battle wasn’t one-sided – the RAF fought the Luftwaffe in the skies and did have some wins – on 15th September (a day known as Battle of Britain Day), for example, they shot down some 60 aircraft attacking London for the loss of less than 30 British fighters.

It was this victory which led the Germans to reduce the number of daylight attacks in favour of night-time raids which, until the launch of the RAF’s night-time fighters in 1941, meant they met little effective resistance. This included that of ground defences – throughout December, 1940, it’s said that anti-aircraft fire only brought down 10 enemy planes.

Yet, the Blitz did not lead to a German victory. For the Nazi regime, the purpose of the constant bombing of London (and other cities) was aimed at sapping the morale of its residents to the extent that they would eventually be forced to beg for peace. But the plan failed and Londoners, digging deep, proved their mettle in the face of fear.

Hundreds of thousands of people were involved in Civil Defence working in a range of jobs – everything from air raid shelter wardens to rescue and demolition teams – and worked alongside firefighters whose numbers were supplemented by an auxiliary service. Naturally all suffered a high level of casualties.

As the weeks passed, the carnage mounted in terms of the loss of and damage to life, destruction of property and psychological toll. And yet the Londoners – sheltering Underground, most famously in the tunnels of the Tube – survived and, as had been the case after the first Great Fire of London, the ruined city was eventually rebuilt.

There are numerous Blitz-related memorials in London, many related to specific bombings. But among the most prominent are the National Firefighters Memorial, located opposite St Paul’s Cathedral, which pays tribute to the firefighters who lost their lives in the war (as well as in peacetime), and a riverside memorial in Wapping honouring civilians of East London killed in the Blitz.

10 London ‘battlefields’ – 9. The Battle of Cable Street…

We hit the 20th century with this London ‘battle’, a confrontation in Stepney between police and a range of anti-fascist and fascist forces in the lead-up to World War II.

The ‘battle’ took place on a Sunday – 4th October, 1936 – following a summer of anti-Semitic violence and was sparked by a decision by the British Union of Fascists, led by Sir Oswald Mosley , to march through the East End, then the heartland of London’s Jewish community.

The ‘battle’ took place on a Sunday – 4th October, 1936 – following a summer of anti-Semitic violence and was sparked by a decision by the British Union of Fascists, led by Sir Oswald Mosley , to march through the East End, then the heartland of London’s Jewish community.

Incensed at the plans (and faced with government inaction despite calls for the march to be called off), anti-fascist protestors – which included large numbers of Jewish and Irish people as well as trade unionists, communists, socialists, anarchists and local residents – gathered initially at Gardiner’s Corner (named for a department store which once on the site at the junction of Whitechapel High Street and Commercial Road) to prevent the march.

The protestors were chanting and carrying banners which read “No Parasan” (“They shall not pass”, a slogan taken from anti-fascist forces who used it during the Spanish Civil War).

Estimates as to how many people turned out in protest vary widely – from 100,000 people up to as many as 250,000 or even 500,000 – but it’s clear that whatever the actual number, the crowd was huge and vastly outnumbered the up to 3,000 fascists – known as Blackshirts – who turned up to march and the 10,000 Metropolitan Police officers, some of whom were on horseback, sent to prevent the march from being disrupted.

With the path blocked despite police charges into the crowd, Mosley and his Blackshirts were advised by authorities to head south to Cable Street but there they encountered road-blocks made from furniture, paving stones and even apparently overturned lorries which appeared at the street’s west end, around the junction with Christian Street.

Police again attempted to clear the road but were blocked by the makeshift barricades and a wall of protestors while residents in houses lining the streets threw rubbish and even the contents of chamber pots at them. Police responded by sending in squads of men to snatch the ringleaders of the protests; protestors responded by ‘kidnapping’ some police officers.

Faced with continuing violence, Mosley was forced to abandon the march and the BUF were dispersed back through the City of London. The protestors meanwhile were said to have turned the event into a giant street party in celebration of their victory.

More than 100 people were said to have been injured in the violence and some 150 of the demonstrators were arrested. Most of the charges were of a minor nature but some of the ringleaders were given up to three year terms of imprisonment.

A large mural depicting the battle was painted on the side of St George’s Town Hall in Cable Street in the 1980s and there’s also a red plaque in nearby Dock Street (pictured) commemorating the incident.

Aside from a victory in itself, the battle was the catalyst for the passing of the Public Order Act of 1936 which meant the organisers of marches would henceforth have to seek permission of the police before holding them. It also banned demonstrators from marching in uniform.

PICTURED: A plaque commemorating the ‘battle’ in Dock Street which runs off the west end of Cable Street. Via Richard Allen/Wikipedia

This Week in London – World’s oldest clock and watch collection moves to the Science Museum; commemorating Agincourt; and, black experiences in war at the Imperial War Museum…

• The world’s oldest clock and watch collection can be seen at its new home at the Science Museum in South Kensington from tomorrow. The Clockmaker’s Museum, which was established in 1814 and has previously been housed at City of London Corporation’s Guildhall, has taken up permanent residence in the Science Museum. Assembled by the Worshipful Company of Clockmakers – founded in 1631 – the collection features some 600 watches, 80 clocks and 25 marine timekeepers spanning the period from the 15th century to today. Highlights among the collection include: a year duration long case clock made by Daniel Quare of London (c. 1647-1724); a star-form watch (pictured) by David Ramsay, first master of the Clockmaker’s Company; the 5th marine timekeeper completed in 1770 by John Harrison (winner in 1714 of the Longitude Prize); a timekeeper used by Captain George Vancouver on his 18th century voyage around the Canadian island that bears his name; a watch used to carry accurate time from Greenwich Observatory around London; and, a wristwatch worn by Sir Edmund Hillary when he summited Mount Everest in 1953. The collection complements that already held by the Science Museum in its ‘Measuring Time’ gallery – this includes the third oldest clock in the world (dating from 1392, it’s on loan from Well’s Cathedral) and a 1,500-year-old Byzantine sundial-calendar, the second oldest geared mechanism known to have survived. Entry is free. For more, see www.sciencemuseum.org.uk/clocks. PICTURE: The Worshipful Company of Clockmakers.

• The world’s oldest clock and watch collection can be seen at its new home at the Science Museum in South Kensington from tomorrow. The Clockmaker’s Museum, which was established in 1814 and has previously been housed at City of London Corporation’s Guildhall, has taken up permanent residence in the Science Museum. Assembled by the Worshipful Company of Clockmakers – founded in 1631 – the collection features some 600 watches, 80 clocks and 25 marine timekeepers spanning the period from the 15th century to today. Highlights among the collection include: a year duration long case clock made by Daniel Quare of London (c. 1647-1724); a star-form watch (pictured) by David Ramsay, first master of the Clockmaker’s Company; the 5th marine timekeeper completed in 1770 by John Harrison (winner in 1714 of the Longitude Prize); a timekeeper used by Captain George Vancouver on his 18th century voyage around the Canadian island that bears his name; a watch used to carry accurate time from Greenwich Observatory around London; and, a wristwatch worn by Sir Edmund Hillary when he summited Mount Everest in 1953. The collection complements that already held by the Science Museum in its ‘Measuring Time’ gallery – this includes the third oldest clock in the world (dating from 1392, it’s on loan from Well’s Cathedral) and a 1,500-year-old Byzantine sundial-calendar, the second oldest geared mechanism known to have survived. Entry is free. For more, see www.sciencemuseum.org.uk/clocks. PICTURE: The Worshipful Company of Clockmakers.

• Westminster Abbey is kicking off its commemorations of the 600th anniversary of the Battle of Agincourt by opening Henry V’s chantry chapel in Westminster Abbey to a selected few on Saturday night, the eve of the battle’s anniversary. The chapel, which is above the king’s tomb at the east end of the abbey, will be seen by the winners of a public ballot which opened in September. It has never before been officially opened for public tours. The chapel is one of the smallest of the abbey’s chapels. It is occasionally used for services but, measuring just seven by three metres, is not usually open to the public because of size and access issues. Meanwhile the abbey will hold a special service of commemoration on 29th October in partnership with charity Agincourt600 and on 28th October, will host a one day conference for Henry V enthusiasts entitled Beyond Agincourt: The Funerary Achievements of Henry V. For more, see www.westminster-abbey.org/events/agincourt.

• The role the black community played at home and on the fighting front during conflicts from World War I onward is the focus of a programme of free events and tours as Imperial War Museums marks Black History Month during October. IWM London in Lambeth will host a special screening of two documentary films – Burma Boy and Eddie Noble: A Charmed Life – telling the stories of African and Caribbean mean who served in World War II on 25th October. IWM London will also feature a series of interactive talks from historians revealing what it was like for black servicemen during both world wars from this Saturday until Sunday, 1st November. For more, see www.iwm.org.uk.

Send all items for inclusion to exploringlondon@gmail.com.

This Week in London – MC Escher at Dulwich; West Africa’s literary history at the British Library; and, two new war-related exhibitions…

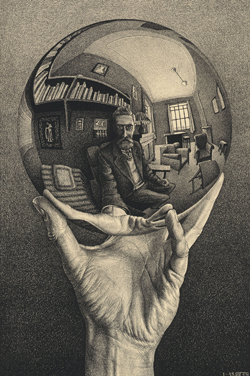

• The first major UK retrospective of the work of 20th century Dutch artist Maurits Cornelis (MC) Escher opened at Dulwich Picture Gallery in London’s south yesterday following its run at the Scottish National Gallery of Art. The Amazing World of MC Escher showcases more than 100 works – including original drawings, prints, lithographs, and woodcuts – as well as previously unseen archive material from the collection of Gemeentenmuseum Den Haag in The Netherlands. Arranged chronologically, highlights include 1934’s Still Life with Mirror – perhaps the first time the artist used surreal illusion, well-known 1948 lithograph Drawing Hands, the almost four metre long 1939-40 woodcut Metamorphosis II, the 1943 lithograph Reptiles and two of his most celebrated works, Ascending and Descending (1960) and Waterfall (1961). Runs until 17th January and is accompanied by a series of special events. Admission charge applies. For more, see www.dulwichpicturegallery.org.uk. PICTURE: M.C. Escher, Hand with Reflecting Sphere (Self-Portait in Spherical Mirror), January 1935, Collection Gemeentemuseum Den Haag, The Hague, The Netherlands/All M.C. Escher works © 2015 The M.C. Escher Company-The Netherlands. All rights reserved. http://www.mcescher.com.

• The first major UK retrospective of the work of 20th century Dutch artist Maurits Cornelis (MC) Escher opened at Dulwich Picture Gallery in London’s south yesterday following its run at the Scottish National Gallery of Art. The Amazing World of MC Escher showcases more than 100 works – including original drawings, prints, lithographs, and woodcuts – as well as previously unseen archive material from the collection of Gemeentenmuseum Den Haag in The Netherlands. Arranged chronologically, highlights include 1934’s Still Life with Mirror – perhaps the first time the artist used surreal illusion, well-known 1948 lithograph Drawing Hands, the almost four metre long 1939-40 woodcut Metamorphosis II, the 1943 lithograph Reptiles and two of his most celebrated works, Ascending and Descending (1960) and Waterfall (1961). Runs until 17th January and is accompanied by a series of special events. Admission charge applies. For more, see www.dulwichpicturegallery.org.uk. PICTURE: M.C. Escher, Hand with Reflecting Sphere (Self-Portait in Spherical Mirror), January 1935, Collection Gemeentemuseum Den Haag, The Hague, The Netherlands/All M.C. Escher works © 2015 The M.C. Escher Company-The Netherlands. All rights reserved. http://www.mcescher.com.

• West Africa’s literary history comes under examination in a new exhibition opening at the British Library at St Pancras on Friday. West Africa: Word, Symbol, Song features more than 200 manuscripts, books, sound and film recordings, artworks, masks and textiles taken from the library’s African collections and elsewhere. It explores how key figures – from Nobel Prize winning Nigerian author Professor Wole Soyinka through to human rights activist Fela Kuti, the creator of Afrobeat, and a generation of enslaved 18th century West Africans who agitated for the abolition of the slave trade – used words to both build society and fight injustice. Key items on show include a 1989 letter Kuti wrote to the president of Nigeria, General Ibrahim Babangida, in which he agitated for political change, a pair of atumpan ‘talking drums’ similar to those still used in Ghana, a carnival costume newly designed by Brixton-based artist Ray Mahabir, and letters, texts and life accounts written by the most famous 18th century British writer of African heritage, Olaudah Equiano, enslaved and freed scholar Ayuba Suleiman Diallo, and Phillis Wheatley, who, enslaved as a child, went on to write Romantic poetry. The exhibition, which will be accompanied by a major series of talks, events and performances, runs until 16th February. Admission charge applies. For more, see www.bl.uk/west-africa-exhibition.

• Two new war related exhibitions opened in London this week. Opened on Monday at the City of London’s Guildhall Library, Talbot House – An Oasis in a World Gone Crazy, recounts the story of army chaplains Philip ‘Tubby’ Clayton and Neville Talbot and their creation of an Everyman’s Club – where countless soldiers spent time away from the fighting – in a house in the Belgian town of Poperinge, a few miles from the frontline at Ypres. The exhibition, created to celebrate the centenary of the house’s creation in 1915, features items from Talbot House, the memoirs of ‘Tubby’ and part of the hut where he wrote them after fleeing the Germans. Runs until 8th January and the exhibition also features two ticketed events. Entry to the exhibition is free. For more, follow this link. Meanwhile, Lee Miller: A Woman’s War opens at the Imperial War Museum in Lambeth today, displaying 150 photographs depicting women’ experiences during World War II. The four part exhibition looks at women before the war, in wartime Britain, in wartime Europe and after the war. Runs until 24th April. Admission charge applies. For more, see www.iwm.org.uk.

Send all items for inclusion to exploringlondon@gmail.com.

Lost London – Church of St Alban, Wood Street…

This church, which survived until it was largely destroyed by bombing in World War II, isn’t completely lost – its tower still survives in the middle of Wood Street in the City.

The church, one of a number dedicated to St Alban (Britain’s first Christian martyr) in London throughout its history, was medieval in origin although it has been argued its foundation dates back to the 8th century Saxon King Offa of Mercia who is believed to have had a palace here with the chapel on this site (Offa is also credited as the founder of St Alban’s Abbey).

The church, one of a number dedicated to St Alban (Britain’s first Christian martyr) in London throughout its history, was medieval in origin although it has been argued its foundation dates back to the 8th century Saxon King Offa of Mercia who is believed to have had a palace here with the chapel on this site (Offa is also credited as the founder of St Alban’s Abbey).

The church had fallen into disrepair by the early 17th century and was demolished and rebuilt in 1630s. It proved unfortunate timing for only 32 years later it was completely destroyed again, this time in the Great Fire of London.

Following the Great Fire, the church, now combined with the parish of St Olave, Silver Street, was among those rebuilt to the designs of Sir Christopher Wren and completed in the mid-1680s.

It was restored in the late 1850s under the eye of Victorian architect Sir George Gilbert Scott and the four pinnacles on the tower, which stood on the north side of the church, were replaced later that century.

It survived until World War II when the building was burnt out and partly destroyed on a single night during the Blitz in December, 1940. The remains, with the exception of Wren’s Perpendicular-style tower, were later demolished in the 1950s (by which time the church had been united with the parish of St Vedast, Foster Lane).

The Grade II*-listed tower was converted into a rather unusual private dwelling in the 1980s.

This Week in London – Indian textiles at the V&A; a “typical London street” on show; and, Nobel laureate given Blue Plaque…

• A spectacular tent used by the Tipu Sultan, ruler of the 18th century Kingdom of Mysore (pictured), is among highlights in an exhibition exploring the “incomparably rich world” of handmade textiles from India which opens at the V&A in South Kensington on Saturday. Part of the V&A’s India Festival marking the 25th anniversary of the opening of the museum’s Nehru Gallery, The Fabric of India has exhibits ranging from the earliest known Indian textile fragments (dating from the 3rd century) through to contemporary fashions. Among the around 200 handmade objects – which include everything from ancient ceremonial banners and sacred temple hangings to modern saris and bandanna handkerchiefs – are a Hindu narrative cloth depicting avatars of Vishnu dating from about 1570, an 18th century crucifixion scene made for an Armenian Christian church in south-east India, block-printed ceremonial textiles from Gujarat – made in the 14th century for the Indonesian market, bed-hangings originally belonging to the Austrian Prince Eugene (1663-1736), and a selection of clothing made using Khadi, a cloth which Mahatma Gandhi promoted using in the 1930s when he asked people to make the fabric as a symbol of resistance to colonial rule. Admission charges apply. Runs until 10th January. For more see, www.vam.ac.uk/fabricofindia. PICTURE: © National Trust Images.

• A spectacular tent used by the Tipu Sultan, ruler of the 18th century Kingdom of Mysore (pictured), is among highlights in an exhibition exploring the “incomparably rich world” of handmade textiles from India which opens at the V&A in South Kensington on Saturday. Part of the V&A’s India Festival marking the 25th anniversary of the opening of the museum’s Nehru Gallery, The Fabric of India has exhibits ranging from the earliest known Indian textile fragments (dating from the 3rd century) through to contemporary fashions. Among the around 200 handmade objects – which include everything from ancient ceremonial banners and sacred temple hangings to modern saris and bandanna handkerchiefs – are a Hindu narrative cloth depicting avatars of Vishnu dating from about 1570, an 18th century crucifixion scene made for an Armenian Christian church in south-east India, block-printed ceremonial textiles from Gujarat – made in the 14th century for the Indonesian market, bed-hangings originally belonging to the Austrian Prince Eugene (1663-1736), and a selection of clothing made using Khadi, a cloth which Mahatma Gandhi promoted using in the 1930s when he asked people to make the fabric as a symbol of resistance to colonial rule. Admission charges apply. Runs until 10th January. For more see, www.vam.ac.uk/fabricofindia. PICTURE: © National Trust Images.

• Westbury Road in Bounds Green, Haringey, is the subject of a new photographic and art exhibit which opened at the Geffrye Museum in Shoreditch this week. A Street Seen: The Residents of Westbury Road is a collaborative exhibition featuring the works of photographer Andrew Buurman and artist Gabriela Schutz as they document the homes, gardens and residents of what is described as a “typical London street”. The display includes a six metre long panoramic drawing of Victorian houses by Schutz and a series of photographs depicting residents in their back gardens taken over a two year period by Buurman. Runs until 3rd April. For more, see www.geffrye-museum.org.uk.

• One of the founding fathers of sports medicine, Nobel Prize winner AV Hill, has been honoured with an English Heritage blue plaque unveiled at his former home in Highgate in London’s north last month. Hill, as well as being noted for his work in the field of physiology, was also an independent MP during World War II and a humanitarian who is credited with helping more than 900 academics – including 18 Nobel laureates – escape persecution by the Nazis. He lived at the property at 16 Bishopswood Road for 44 years, between 1923 and 1967, 10 years before his death. For more on blue plaques, see www.english-heritage.org.uk/visit/blue-plaques/.

Send all items for inclusion to exploringlondon@gmail.com.

10 small, ‘secret’ and historic gardens in central London…9. Garden of Rest, Marylebone…

This pocket park is another of those located on the site of a former church – in this case the Marylebone Parish Church which now stands to the north.

This pocket park is another of those located on the site of a former church – in this case the Marylebone Parish Church which now stands to the north.

The church – the third to serve the parish – was built here in 1740 but was replaced when the current parish church was built between 1813 and 1817.

The former church didn’t close until 1926, however, continuing use as a parish chapel, and even then wasn’t demolished until 1949 after it was damaged by bombing during World War II.

The former church didn’t close until 1926, however, continuing use as a parish chapel, and even then wasn’t demolished until 1949 after it was damaged by bombing during World War II.

In 1951, the St Marylebone Society created a Memorial Garden of Rest on the site (also known as the Old Church Garden). It was opened in March, 1952, by Viscount Portman.

The foundations of the former church were marked out in the sunken portion of the garden. The predominantly paved garden also contains numerous gravestones and memorials.

These include that of Methodist movement leader Charles Wesley, erected in 1858 to commemorate his burial in 1788 (pictured right). There’s also a plaque recording notable burials at the church, including the painter George Stubbs (1806), royal apothecary John Allen (1774), architect James Gibbs and bare knuckle boxer James Figg (1734). Other plaques detail some of the church’s history.

Also of note in the garden is a Judas tree (Cercis siliquastrum), named for being the variety upon which Judas hung himself or, alternately, because its fruit pods resemble bags of silver. The current tree replaces an earlier one.

WHERE: Garden of Rest Marylebone, Marylebone High Street (nearest tube stations are St Paul’s and Barbican); WHEN: 7am to dusk; COST: Entry is free; WEBSITE: www.myparks.westminster.gov.uk/parks/garden-of-rest-marylebone/.

10 small, ‘secret’ and historic gardens in central London…7. St Swithin’s Church Garden…

Back into the City of London this week and it’s another garden located on the site of a former church.

Back into the City of London this week and it’s another garden located on the site of a former church.

Situated just off Cannon Street, this much overlooked tiny raised garden was created on the site of the former Church of St Swithin. The church is believed to have existed here as early as the 11th century and was replaced, thanks largely to the generosity of Lord Mayor Sir John Hind, with a larger building in the early part of the 15th century – it featured one of the first towers built specifically for the task of hanging bells inside.

The church was among those destroyed in the Great Fire of London in 1666 but, now united with the parish of St Mary Bothaw, was rebuilt to the designs of Sir Christopher Wren shortly after in 1677-88.

The church was among those destroyed in the Great Fire of London in 1666 but, now united with the parish of St Mary Bothaw, was rebuilt to the designs of Sir Christopher Wren shortly after in 1677-88.

Later known as St Swithin, London Stone thanks to the mysterious London Stone being built into the south wall of the church in the late 18th century (for more on the stone and its current location, see our earlier post here), the church survived until World War II when it was damaged beyond repair during bombing and was later destroyed.

Relandscaped in 2010, the garden features a rather dramatic memorial (pictured) to the suffering of women and children in war in general and medieval figure, Catrin Glyndwr in particular. Unveiled in 2001, it was designed by Nic Stradlyn-John and sculpted by Richard Renshaw.

The daughter of the Welsh Prince Owain Glyndwr, she was captured in 1409 and brought with her children and mother to the Tower of London. Catrin and two of her children died in late 1413 and were buried in the former church.

WHERE: St Swithin’s Church Garden, Salters Hall Court off Cannon Street (nearest Tube station is Cannon Street); WHEN: daily; COST: Free; WEBSITE: www.bost.org.uk/open-places/red-cross-garden/.

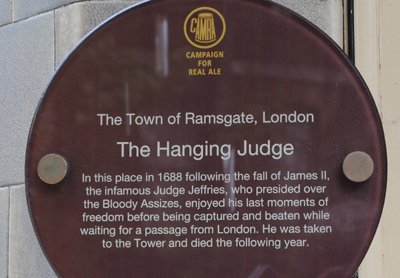

Famous Londoners – Judge Jeffreys…

Best known as the “Hanging Judge” thanks to his role in the so-called Bloody Assizes of 1685, George Jeffreys climbed the heights of England’s legal profession before his ignominious downfall.

Born on 15th May, 1645, at the family home of Acton Hall in Wrexham, North Wales, Jeffreys was the sixth son in a prominent local family. In his early 20s, having been educated in Shrewsbury, Cambridge and London, he embarked on a legal career in the latter location and was admitted to the bar in 1668.

In 1671, he was made a Common Serjeant of London, and despite having his eye on the more senior role of Recorder of London, was passed over. But his star had certainly risen and, despite his Protestant faith, he was a few years later appointed to the position of solicitor general to James, brother of King Charles II and the Catholic Duke of York (later King James II), in 1677.

In 1671, he was made a Common Serjeant of London, and despite having his eye on the more senior role of Recorder of London, was passed over. But his star had certainly risen and, despite his Protestant faith, he was a few years later appointed to the position of solicitor general to James, brother of King Charles II and the Catholic Duke of York (later King James II), in 1677.

The same year he was knighted and became Recorder of London, a position he had long sought, the following year. Following revelations of the so-called the Popish Plot in 1678 – said to have been a Catholic plot aimed the overthrow of the government, Jeffreys – who was fast gaining a reputation for rudeness and the bullying of defendants – served as a prosecutor or judge in many of the trials and those implicated by what turned out to be the fabricated evidence of Titus Oates (Jeffreys later secured the conviction of Oates for perjury resulting in his flogging and imprisonment).

Having successfully fought against the Exclusion Bill aimed at preventing James from inheriting the throne, in 1681 King Charles II created him a baronet. In 1683 he was made Lord Chief Justice and a member of the Privy Council. Among cases he presided over was that of Algernon Sidney, implicated in the Rye House Plot to assassinate the king and his brother (he had earlier led the prosecution against Lord William Russell over the same plot). Both were executed.

It was following the accession of King James II in February, 1685, that Jeffreys earned the evil reputation that was to ensure his infamy. Following the failed attempt by James Scott, 1st Duke of Monmouth and illegitimate son of the late King Charles II, to overthrow King James II, Jeffreys was sent to conduct the trials of the captured rebels in West Country towns including Taunton, Wells and Dorchester – the ‘Bloody Assizes’.

Of the almost 1,400 people found guilty of treason in the trials, it’s estimated that between 150 and 200 people were executed and hundreds more sent into slavery in the colonies. Jeffreys’, meanwhile, was busy profiting financially by extorting money from the accused.

By now known for his corruption and brutality, that same year he was elevated to the peerage as Baron Jeffreys of Wem and named Lord Chancellor as well as president of the ecclesiastical commission charged with implementing James’ unpopular pro-Catholic religious policies.

His fall was to come only a couple of years later during Glorious Revolution which saw King James II overthrown by his niece, Mary, and her husband William of Orange (who become the joint monarchs Queen Mary II and King William III).

Offered the throne by a coalition of influential figures who feared the creation of a Catholic dynasty following the birth of King James II’s son, James Francis Edward Stuart, William and Mary arrived in England with a large invasion force. King James II’s rule collapsed and he eventually fled the country.

Remaining in London after the king had fled, Lord Jeffreys only attempted to flee as William’s forced approached the city. He made it as far as Wapping where, despite being disguised as a sailor, he was recognised in a pub, now The Town of Ramsgate (pictured above).

Placed in custody in the Tower of London, he died there of kidney problems on 18th April, 1689, and was buried in the Chapel Royal of Saint Peter ad Vincula (before, in 1692, his body was moved to the Church of St Mary Aldermanbury). All traces of his tomb were destroyed when the church was bombed during the Blitz (for more on the church, see our earlier post here).

Daytripper – Secret wartime tunnels open at White Cliffs…

A series of secret tunnels, built behind the famous White Cliffs of Dover on the orders of former British PM Winston Churchill, have opened to the public for the first time.

More than 50 volunteers along with archaeologists, engineers, mine consultants and a geologist, spent two years excavating and restoring the tunnels which, known as the Fan Bay Deep Shelter, were aimed at housing men manning gun batteries designed to prevent German ships from moving freely in the English Channel.

The shelter, which was personally inspected by Churchill in June, 1941, provided accommodation for four officers and up to 185 men in five bomb-proof chambers for use during bombardments as well as a hospital and a store room. It was originally dug by Royal Engineers from the 172nd Tunnelling Company in just 100 days.

The tunnels, which were decommissioned in the 1950s and then filled in during the 1970s, were discovered after the National Trust bought the land above in 2012. More than 100 tonnes of soil and rubble were removed during the excavation.

Specialist guides now take visitors on 45 minute, torch-lit, hard hat tours into the shelter – the largest of its kind in Dover, taking visitors down the original 125 steps into the tunnels 23 metres below the surface. Inside can be seen graffiti dating from the war which includes the names of men stationed there as well as ditties and drawings. Other personal mementoes include homemade wire hooks, a needle and thread and ammunition.

Back above ground, there are two World War I sound mirrors which were originally designed to give advance warning of approaching aircraft but which had become obsolete when radar technology was invented in 1935 (pictured in action below).

The tunnels complement those which are already open at Dover Castle (managed by English Heritage).

WHERE: Fan Bay Deep Shelter, Langdon Cliffs, Upper Road, Dover (nearest train station is Dover Priory (two miles); WHEN: Guided tours only – from 9.30am daily until 6th September – tours then on weekdays only until 30th September); COST:£10 adults/£5 children (aged 12-16) (free for National Trust members); WEBSITE: www.nationaltrust.org.uk/white-cliffs-dover.

PICTURE: Top – National Trust/Barry Stewart/; Bottom – National Trust/Crown Copyright.

10 small, ‘secret’ and historic gardens in central London…4. St Mary Aldermanbury Gardens…

Like St Dunstan in the East, these gardens at the corner of Love Lane and Aldermanbury are also based inside the remains of a medieval church.

Like St Dunstan in the East, these gardens at the corner of Love Lane and Aldermanbury are also based inside the remains of a medieval church.

The church of St Mary Aldermanbury (the name may relate to its proximity close to Guildhall, or the ‘Alderman’s Bury’ or ‘Alderman’s Hall’), mentioned as far back as the late 12th century, was destroyed in the Great Fire of London but was among those rebuilt to the designs of Sir Christopher Wren only to be destroyed again during the Blitz in 1940.

This time there was to be no rebuilding and instead, in 1966 the walls – all that remained – were moved more than 4,000 miles away to the town of Fulton, Missouri, in the US.

This time there was to be no rebuilding and instead, in 1966 the walls – all that remained – were moved more than 4,000 miles away to the town of Fulton, Missouri, in the US.

There they were reconstructed in the grounds of Westminster College – site of Winston Churchill’s famous “Iron Curtain” speech in 1946 – and the church restored as a memorial to the former British PM. The National Churchill Museum is located beneath.

There’s plaque mentioning this in the gardens (and featuring an image of what the church looked like after its reconstruction in Fulton) which still contains the church’s footings (these date from the 15th century when the church was apparently partially rebuilt) and give an indication of what the church’s footprint would have been along with headstones (among those whose remains were buried here was the notorious Judge Jeffreys).

Other features include a memorial to Henry Condell and John Heminge, both involved in the publication of William Shakespeare’s first folio (you can read more about it in our earlier post here).

The garden was laid out after the church was removed. It is a designated Site of Local Importance for Nature Conservation and attracts wildlife including birds such as blackbirds, woodpigeons, house sparrows and blue tits. Plantings were added in 2011 to maximise the attraction to bird as well as bees and butterflies. On the corner outside the garden is a fountain.

WHERE: St Mary Aldermanbury Garden, Aldermanbury, City of London (nearest Tube stations are St Pauls and Monument); WHEN: 8am to 7pm daily; COST: Free; WEBSITE: www.cityoflondon.gov.uk/things-to-do/green-spaces/city-gardens/visitor-information/Pages/St-Mary-Aldermanbury.aspx.

10 small, ‘secret’ and historic gardens in central London…3. St Dunstan in the East Garden…

Located amid the remains of the medieval church of St Dunstan in the East, the garden was created in the late 1960s after the church was finally – and irrevocably, apparently – destroyed in the Blitz of World War II.

The church’s origins went back to around 1100 and it was subsequently extended with a new south aisle in the late 14th century and repaired in the early 17th century before being severely damaged in the Great Fire of 1666.

The church’s origins went back to around 1100 and it was subsequently extended with a new south aisle in the late 14th century and repaired in the early 17th century before being severely damaged in the Great Fire of 1666.

Patched up, with a new steeple and tower added to the building between 1695-1701 by Sir Christopher Wren, the building stood until the early 19th century when much of the church – with the exception of Wren’s additions – had to be rebuilt (for more on the history of the church, see our earlier Lost London post here).

The ‘new’ building was, however, badly damaged during bombing in 1941 and it was decided not to rebuild the church in the aftermath of the war.

The City of London opened a garden, sympathetic with the remains of the Grade I-listed building, on the site in 1971 (although Wren’s tower remains). They won a landscape award only a few years later.

Features in these atmospheric gardens – which seem to capture the essence of the Romantic idea of what ruins should look like – include a fountain which sits in the middle of the nave. In 2010 it was one of five public gardens in the City where award-winning ‘insect hotels’ were installed.

Maintenance works were carried out in 2015 and new plantings put in (the picture, above, was taken before this).

WHERE: St Dunstan in the East, between Idol Lane and St Dunstan’s Hill, City of London (nearest Tube stations are Monument and Tower Hill); WHEN: 8am to 7pm or dusk (whichever is earlier); COST: Free; WEBSITE: www.cityoflondon.gov.uk/things-to-do/green-spaces/city-gardens/visitor-information/Pages/St-Dunstan-in-the-East.aspx

10 small, ‘secret’ and historic gardens in central London…2. Whittington Garden…

The history of this City of London garden can be immediately spotted in the garden’s name.

It’s named for Richard (Dick) Whittington, a four time medieval mayor of London whose name (and cat) has been immortalised in stories and rhymes which continue to be retold in Christmas pantomimes every year (you can read more about the real Dick Whittington in our earlier post here).

The reason for the garden’s name is in its proximity to the church of St Michael Paternoster Royal – it stands on the other side of College Street – which he poured money into rebuilding during his lifetime and where he was buried (you can read more about the building here). You can also see a Blue Plaque on the former site of Whittington’s house further up College Hill.

The reason for the garden’s name is in its proximity to the church of St Michael Paternoster Royal – it stands on the other side of College Street – which he poured money into rebuilding during his lifetime and where he was buried (you can read more about the building here). You can also see a Blue Plaque on the former site of Whittington’s house further up College Hill.

The garden (pictured above looking across to the church) stands on what was the river bank during the Roman era at the bottom of College Hill. It was previously the site of buildings connected with the fur trade but these suffered bomb damage during World War II and were subsequently demolished.

The City of London Corporation acquired the site in 1955 and laid out the gardens in 1960 and the small fountain now found there dates from later that decade.

The gardens, which contain some substantial trees and lawn areas as well as hedges and flower beds, were refurbished in 2005. Features include two granite plinths upon which sit two horsemen (pictured). Sculpted by Italian sculptor Duilio Cambellotti, they were presented to the City of London by the Italian President during a state visit in 2005.

WHERE: Whittington Garden, between College Street and Upper Thames Street, City of London (nearest Tube station is Cannon Street); WHEN: Anytime; COST: Free; WEBSITE: www.cityoflondon.gov.uk/things-to-do/green-spaces/city-gardens/visitor-information/Pages/Whittington-Garden.aspx.

10 small, ‘secret’ and historic gardens in central London…1. Goldsmiths’ Garden…

Welcome to the first in our new Wednesday series, looking at some of central London’s small historic gardens which, while not secret in the strictest sense of the word, may tend to get overlooked. Each of the gardens we’re looking at is accessible to the public and has a link to the city’s history as well as providing a peaceful oasis out of the hustle and bustle…

First up, it’s the Goldsmiths’ Garden, located on the site of the former medieval church of St John Zachary at the corner of Gresham and Noble Streets in the City.

The church, which dates back to at least the late 12th century, was destroyed in the Great Fire of London in 1666 and not rebuilt (its parish was united with that of St Anne and St Agnes) although its ruins apparently remained until the 19th century. The church’s layout can be seen in the sunken area of the current garden.

The church, which dates back to at least the late 12th century, was destroyed in the Great Fire of London in 1666 and not rebuilt (its parish was united with that of St Anne and St Agnes) although its ruins apparently remained until the 19th century. The church’s layout can be seen in the sunken area of the current garden.

The Worshipful Company of Goldsmiths had acquired land in the area in medieval times and built their first hall here in 1339 on the site of the current hall (which lies across the road from the garden and dates from the early 19th century).

The first garden was constructed on the site of the former church in 1941 by fire watchers after the area suffered in the Blitz and it apparently won a Gardener’s Company award for “Best Garden on a Blitzed Site” in 1950.

The garden has since been altered and refurbished several times since, including in around 1960 by landscape architect Sir Peter Shepheard and in the 1990s by landscape architect Anne Jennings.

Features today include the iron entrance archway (top) which was commissioned by the Blacksmiths Company during the 1990s renovation. It features the leopard’s head hallmark of the Goldsmiths’ Company Assay Office, used to verify the purity of silver since the early 14th century.

Features today include the iron entrance archway (top) which was commissioned by the Blacksmiths Company during the 1990s renovation. It features the leopard’s head hallmark of the Goldsmiths’ Company Assay Office, used to verify the purity of silver since the early 14th century.

As well as the central fountain installed in the 1990s (and donated by the Constructors’ Company), the garden also features a two metre high, 2.5 tonne Portland stone monument called the Three Printers (pictured right).

The work of Wilfred Dudeney, it was commissioned by the Westminster Press Group in the late 1950s for their new headquarters in New Street Square, off Fleet Street, and depicts a newsboy, editor and printer. It was placed in a demolition yard in Watford when the group moved headquarters before taking its current position in 2009.

WHERE: Goldsmiths’ Garden, corner of Gresham and Noble Streets, City of London (nearest Tube stations are St Paul’s, Bank and Barbican); WHEN: Anytime; COST: Free; WEBSITE: www.thegoldsmiths.co.uk/goldsmiths’-hall/.

For more on London’s parks and gardens, check out Jill Billington’s London’s Parks and Gardens.

10 sites from London at the time of the Magna Carta – 10. Priory of the Order of St John of Jerusalem…

Founded in Clerkenwell in 1144, the Priory of the Order of St John of Jerusalem served as the order’s English headquarters.

The order, also known as the Knights Hospitaller, was founded in Jerusalem in 1080 to care for the sick and poor, and soon spread across Europe with the English ‘branch’ established on 10 acres just outside the City walls apparently by a knight, Jorden de Briset.

The original buildings – of which only the 12th century crypt (pictured above) survives complete with some splendid 16th century tomb effigies including that of the last prior, Sir William Weston – included a circular church, consecrated in 1185, and monastic structures including cloisters, a hospital, living quarters and a refectory or dining hall.

There are records of dignitaries staying at the priory as it grew in size and renown – among them was King John who in 1212, apparently stayed here for an entire month. There are also surviving accounts of Knights Hospitaller riding out in procession from the priory and through the City at the start of a journey to the Holy Land.

The priory and church were attacked during the Peasant’s Revolt of 1381, thanks to its connection with the hated Poll Tax (Prior Robert Hales was also the Lord High Treasurer and was beheaded during the revolt on Tower Hill).

The church was subsequently rebuilt as a rectangular-shaped building and then, in the early 16th century, enlarged when the site was significantly renovated. These renovations were still relatively new when the priory was dissolved in 1540 during the Dissolution of King Henry VIII.

The priory church, which survived the Great Fire of 1666, was later used as a parish church but was destroyed in an air raid in World War II. Subsequently rebuilt, it can be visited today along with the crypt below and the cloister garden, created in the 1950s as a memorial to St John’s Ambulance members from the London area (the original shape of the circular church is picked out in the paving here).

Perhaps the most famous building to survive is St John’s Gate which dates from the 16th century and was once the gatehouse entrance to the priory (added in the final renovations).

After the Dissolution it served various roles including as the office of the Master of Revels (where Shakespeare’s plays were licensed), the home of The Gentleman’s Magazine (Samuel Johnson was among contributors and worked on site), a coffee house (run by William Hogarth’s father) and a public house called the Old Jerusalem Tavern (yes, Charles Dickens was said to be a regular). It is now home to the recently renovated Museum of the Order of St John (you can see our earlier post on the museum here).

WHERE: Museum of the Order of St John, St John’s Gate (and nearby priory church), St John’s Lane, Clerkenwell (nearest Tube stations is Farringdon); WHEN: 10am to 5pm, Monday to Saturday (tours are held at 11am and 2.30pm on Tuesday, Friday and Saturday); COST: Free (a suggested £5 donation for guided tours); WEBSITE: www.museumstjohn.org.uk.

We’ll kick off a new Wednesday series next week…

10 sites from London at the time of the Magna Carta – 6. St Helen’s Bishopsgate…

This church in the shadow of 30 St Mary Axe (aka The Gherkin) is all that remains of a Benedictine nunnery that was founded here during the reign of King John in 1210.

Established by one “William, son of William the goldsmith” after he was granted the right by the Dean and Chapter of St Paul’s Cathedral, the priory was built to the north of a previously existing church with a new church for the nuns to use built right alongside the existing structure (thus accounting for the rarely seen side-by-side naves of the current building).

Established by one “William, son of William the goldsmith” after he was granted the right by the Dean and Chapter of St Paul’s Cathedral, the priory was built to the north of a previously existing church with a new church for the nuns to use built right alongside the existing structure (thus accounting for the rarely seen side-by-side naves of the current building).

While the new church was built longer than the existing church, the latter was then lengthened to give them both the same length. A line of arches and a screen separated the nun’s choir and the parish church.

The church which stands today has been much altered over the centuries and what we now see there largely dates from the 14th and 15th centuries (although the bell turret which sits over the west front is an 18th century addition).

One of the priory’s claims to fame in medieval times was that it apparently was once home to a piece of the True Cross, presented by King Edward I in 1285.

The nunnery was dissolved in 1538 during the Great Dissolution of King Henry VIII and the buildings, excepting the church, sold off to the Leathersellers’ Company (all were eventually demolished by the 18th century). The screen separating the nun’s choir and the parish church, meanwhile, was removed, leaving the main body of the church as it can be seen today.

The now Grade I-listed church, which was William Shakespeare’s parish church when he lived in the area in the 1590s, survived both the Great Fire of London and the Blitz but was severely damaged by two IRA bombs in the early 1990s leading to some major – and controversial – works under the direction of architect Quinlan Terry.

Inside the church today is a somewhat spectacular collection of pre-Great Fire monuments including the 1579 tomb of Sir Thomas Gresham, founder of the Royal Exchange, the 1636 tomb of judge, MP and Chancellor of the Exchequer, Sir Julius Caesar Adelmare, and the 1476 tomb of merchant, diplomat, City of London alderman and MP, Sir John Crosby.

It was also once the site of the grave of 17th century scientist Sir Robert Hooke but these were apparently removed from the church crypt in the 19th century when repairs to the floor of the nave were being made and placed in an unmarked common grave. Their location apparently remains unknown.

WHERE: St Helen’s Bishopsgate, Great St Helens (nearest Tube stations are Aldgate, Bank and Liverpool Street); WHEN: 9.30am to 12.30pm weekdays daily (also usually open Monday, Wednesday and Friday afternoons but visitors are advised to telephone first); COST: Free; WEBSITE: www.st-helens.org.uk.