This year marks the 500th anniversary of the building of Hampton Court Palace in Greater London’s south-west. We speak to Sheila Dunsmore, a State Apartment warder at Hampton Court Palace (pictured above in centre on the left)…

1. It’s Hampton Court Palace’s 500th anniversary – who first built the palace and why? “In 1514, Thomas Wolsey came to survey the land at Hampton Court. He wanted to find a suitable place to build a sumptuous country retreat away from the dirt of London, but close enough to the capital to travel back for meetings. It was also to be a place to entertain the important company his position as Archbishop of York provided, of which none were more important than young King Henry VIII.”

2. Where are the oldest parts of the palace today? “The oldest part of the palace is the Tudor kitchens, more specifically the area were the great fire is. This was once part of Sir Giles Daubeney’s original kitchen, and dates back to the manor already on the site when it was acquired by Wolsey. Sir Giles Daubeney was Lord Chamberlain to Henry VII, and acquired an 80 year lease on the property from the Knights Hospitallers of St John of Jerusalem, the then owners. The bell in the tower above the astronomical clock is also said to have come from the Knights Hospitallers’ original manor house.”

3. Hampton Court’s 500 years of history spans a number of definable eras – from Tudor to the 21st century. Which is your favourite and why? “My favourite era is the 1660s when Charles II came back to England to take up his rightful place as king. Although visitors do not really associate Charles with the palace, he did spend time here, most famously his honeymoon!”

4. With this in mind what is your favourite part of the palace? “I love the west front façade – it just looks so imposing and mysterious. Whether you are driving or walking past it it’s guaranteed to draw you in under its spell!”

5. Do you have a favourite anecdote from the palace’s history? “I love the story of Horace Beauchamp Seymour, a dashing military hero who had fought at the Battle of Waterloo. He came to live at the palace in 1827 and, as a handsome eligible widower, he caused quite a sensation amongst the ladies, especially when he joined the Sunday services at the Chapel Royal. It was not long before a series of fainting episodes began, with the strategically placed young lady fainting into the arms of the dashing Horace, who then proceeded to carry the lady out and stay with her until she regained her composure. After a third successive Sunday of fainting’s, the epidemic was brought to a swift halt by the aunt of Mr Seymour, herself also a palace resident. The feisty old lady pinned a sign to the chapel door warning any lady feeling faint that forthcoming Sunday that Bransome the dustbin man would be carrying her out. Needless to say the fainting ceased!”

6. A complex of buildings dating back as far as 500 years obviously requires considerable upkeep. What are the greatest challenges with regard to maintaining the palace? “I think the biggest challenge would have to be generating the money to keep restoring and conserving this historic palace. To do this we have to keep making sure that people want to visit, from international tour groups to local families who might visit again and again. To do this teams right across the palace work to create exciting exhibitions, immersive events and guided tours to ensure we’re offering people a memorable experience.”

7. Are there any areas of the palace which remain unseen by the public? And any plans to open further areas up? “The palace contains over 1,000 rooms, and visitors get to discover about a quarter of these during their visit. Some years ago we held a Servants, Soldiers and Suffragettes exhibition in a suite of rooms on the top floor of Fountain Court (previously unseen). It was incredibly popular so I’d imagine that in the future we’d look for other such opportunities to share other areas of the palace with our visitors. For anyone that can’t wait that long, on one night of the year (Halloween no less), our adults-only ghost tour offers the chance to peek behind the scenes and explore some areas of the palace off the beaten track!”

8. Are there any ‘secrets’ about the palace you can reveal to us? “A palace as old and as large as Hampton Court holds its fair share of secrets…When the fire took hold in 1986 it was devastating, but in a strange twist of fate some good came from it as well. As restoration of the damaged interiors took place little secrets were revealed to us; behind wood panelling in King William’s damaged rooms hand prints were found in the plaster from the palace’s builders, and sketches were found from the architects with designs for the rooms, all worked directly onto the bare walls. Most exciting of all, however, was the object found downstairs. During work to return King William’s private dining room (which had lost its original look over the years and been used as a function room for the grace and favour residents) to its former glory, a gun was found behind some wooden panelling. The gun dated from the late 1800s, and had a regimental dinner menu was wrapped around it. This is so intriguing – what was the story behind this gun? Who did it belong to? Why did they hide the weapon?”

9. If someone has just one day to visit the palace, what’s your ideal itinerary? “This is a tricky one, and depends very much on the individual…and the weather! I would say on a sunny day start by enjoying a historic welcome with our costumed interpreters, which really helps to set the scene. If it’s a bit chilly pick up a cloak to wear – you can choose between dressing as a Tudor or Georgian courtier. Heading inside, I’d start in the Tudor State Apartments to discover the rich opulence of Henry VIII’s Hampton Court, then visit the recently opened Cumberland Art Gallery, which contains masterpieces by Rembrandt, Canaletto and Van Dyck. Next I’d take in the baroque splendour of the Queen’s State Apartments, then explore the maze, East Front Garden and Privy Garden (weather permitting!). After a spot of lunch I’d suggest visiting the Mantegna Gallery, then the Young Henry exhibition which explores the life of the young Henry VIII, before finishing the day in King William III’s apartments.”

10. Finally, Historic Royal Palaces has already commemorated the 500th anniversary in numerous ways – from a spectacular fireworks display to a jousting tournament. Are there any more events coming up? “The beginning of September saw our costumed interpreters back with their own inimitable brand of entertainment, while at the end of September we’re hosting a sleepover inside the palace! As the evenings draw in, our popular ghost tours return for the winter season. Even further ahead we’ve got a series of carol evenings and even an ice rink for our visitors to enjoy!”

WHERE: Hampton Court Palace, East Molesey, Surrey (nearest station is Hampton Court from Waterloo); WHEN: 10am to 6pm until 24th October after which it’s open to 4.30pm); COST: Adult £19.30, Concession £16, Child under 16 £9.70 (under fives free), family tickets, garden only tickets and online booking discounts available; WEBSITE:www.hrp.org.uk/HamptonCourtPalace/.

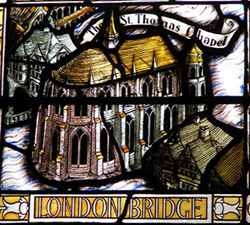

2. Our second most popular article, posted in August, was another in our Lost London series and this time looked at a long-lost feature of Old London Bridge – Lost London – Chapel of St Thomas á Becket.

2. Our second most popular article, posted in August, was another in our Lost London series and this time looked at a long-lost feature of Old London Bridge – Lost London – Chapel of St Thomas á Becket.

• The largest exhibition ever mounted about the life of 17th century diarist Samuel Pepys opens at the National Maritime Museum in Greenwich tomorrow. Samuel Pepys: Plague, Fire, Revolution features more than 200 paintings and objects brought together from museums, galleries and private collections which explore the life of the famous diarist (depicted here in a bust outside the Guildhall Art Gallery) against the backdrop of the tumultuous events of Stuart London, from the execution London of King Charles I in 1649 through the Great Fire of London and the Glorious Revolution on 1688. Objects on show include the famous painting, Portrait of Charles II in Coronation Robes, objects connected to Pepys’ mistresses including one of his love letters to Louise de Kéroualle (aka ‘Fubbs’ or ‘chubby’) and other personal items such as a lute owned by Pepys. The exhibition is accompanied by a series of events including Pepys Show Late: Party like it’s 1669 (26th November) and a series of walks and talks. Admission charge applies. The exhibition runs until 28th March. For more, see

• The largest exhibition ever mounted about the life of 17th century diarist Samuel Pepys opens at the National Maritime Museum in Greenwich tomorrow. Samuel Pepys: Plague, Fire, Revolution features more than 200 paintings and objects brought together from museums, galleries and private collections which explore the life of the famous diarist (depicted here in a bust outside the Guildhall Art Gallery) against the backdrop of the tumultuous events of Stuart London, from the execution London of King Charles I in 1649 through the Great Fire of London and the Glorious Revolution on 1688. Objects on show include the famous painting, Portrait of Charles II in Coronation Robes, objects connected to Pepys’ mistresses including one of his love letters to Louise de Kéroualle (aka ‘Fubbs’ or ‘chubby’) and other personal items such as a lute owned by Pepys. The exhibition is accompanied by a series of events including Pepys Show Late: Party like it’s 1669 (26th November) and a series of walks and talks. Admission charge applies. The exhibition runs until 28th March. For more, see  Little is known of Jack Cade until the former soldier from Kent led an uprising against the rule of King Henry VI during the Hundred Years War with France. And London was a key site of fighting during the uprising.

Little is known of Jack Cade until the former soldier from Kent led an uprising against the rule of King Henry VI during the Hundred Years War with France. And London was a key site of fighting during the uprising.

Another Drury Lane pub, the origins of this one go back to 1852 when it was established by Henry Wells on the site of what was once a potato warehouse.

Another Drury Lane pub, the origins of this one go back to 1852 when it was established by Henry Wells on the site of what was once a potato warehouse.