This district of London, which lies to the south-east of Peckham in the London Borough of Southwark, is believed to owe its name to a local tavern named, you guessed it, the Nun’s Head on the linear Nunhead Green (there’s still a pub there, called The Old Nun’s Head, in a building dating from 1905).

There may well have been actual nuns here (from which the tavern took its name) – it’s suggested that there was a nunnery here which may have been connected to the Augustinian Priory of St John the Baptist founded in the 12th century at Holywell (in what is now Shoreditch).

A local legend gets more specific. It says that when the nunnery was dissolved during the Dissolution, the Mother Superior was executed for her opposition to King Henry VIII’s policies and her head was placed in a spike on the site near the green where the inn was built.

While the use of the name for the area goes back to at least the 16th century, the area remained something of a rural idyll until the 1840s when the Nunhead Cemetery, one of the “Magnificent Seven” cemeteries of Victorian London, was laid out and the area began to urbanise.

A fireworks manufactory – Brocks Fireworks – was built here in 1868 (evidenced by the current pub, The Pyrotechnists Arms). The railway arrived in 1871.

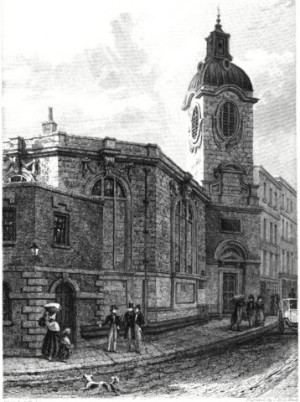

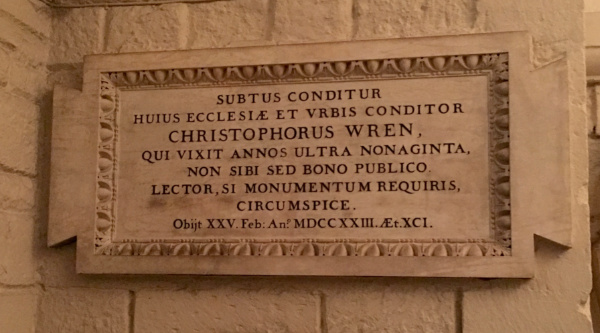

St Antholin’s Church was built in 1877 using funds from the sale of the City of London church, St Antholin’s, Budge Row, which was demolished in 1875. St Antholin’s in Nunhead was destroyed during the Blitz and later rebuilt and renamed St Antony’s (the building is now a Pentecostal church while the Anglican parish has been united with that of St Silas).

There’s also a Dickens connection – he rented a property known as Windsor Lodge for his long-term mistress, actress Ellen Ternan, at 31 Lindon Grove and frequently visited her there (in fact, it has even been claimed that he died at the property and his body was subsequently moved to his home at Gad’s Hill to avoid a scandal).

Nunhead became part of the Metropolitan Borough of Camberwell in 1900. These days, it’s described by Foxtons real estate agency as “a quiet suburb with pretty roads and period appeal”.