A now long gone Franciscan friary located in the north-west of the City of London near Newgate (just to the north of St Paul’s Cathedral), Greyfriars, so known for the color of the friars’ clothing, was the second Franciscan religious house to have been founded in England.

The foundations of the friary date from the early part of the 13th century – the Franciscans, as members of the Order of Friars Minor were known, had arrived in 1224 and are recorded as settling on land granted to them by a rich mercer, John Iwyn, just inside the City wall, in 1225, in the butcher’s quarter of the city.

King Henry III apparently gave them some oak to build their own friary in 1229 and by the mid 1200s, there were more than 80 friars living on the site which was gradually extended over the ensuing years to the north and the west.

King Henry III apparently gave them some oak to build their own friary in 1229 and by the mid 1200s, there were more than 80 friars living on the site which was gradually extended over the ensuing years to the north and the west.

Using funds given them by Sir William Joyner, Lord Mayor of London in 1239, they built a chapel which was later extensively enlarged and improved in the late 13th and early 14th centuries – the new church was said to be 300 feet long – with much of the work funded by Queen Margaret, second wife of King Edward I, and later in the 14th century, Queen Isabella, wife of Edward III. It apparently suffered some damage in a storm in 1343 but was restored by King Edward III.

When it was finally completed in 1348, the church is said to have been the second largest in London. A library was later added to the buildings, founded by the famous Lord Mayor of London, Richard “Dick” Whittington.

Such was the fame of the church that, the heart of Queen Eleanor, wife of King Henry III, was buried here after her death in 1291 while, despite dying at her castle in Marlborough, Queen Margaret was also buried here in 1318 (apparently wearing a Franciscan habit).

But perhaps the most notorious person to be buried here was Queen Isabella, wife of King Edward II and known by many as the “She-Wolf of France”, after her death in 1358. In fact, it’s said that the ghost of Isabella still haunts the former location of Greyfriars, driven forth from the grave for her role in deposing her husband.

Other non royal luminaries said to have been buried here include the 15th century writer Sir Thomas Mallory, author of Le Morte d’Arthur and 16th century Catholic nun Elizabeth Barton, the so-called ‘mad maid of Kent’ who was executed for her rather unwise prophecies predicting King Henry VIII’s death if he married Anne Boleyn.

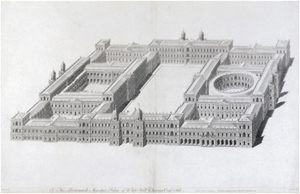

The end of the friary, pictured above in the sixteenth century, came in 1538 when it fell victim to King Henry VIII’s policy of dissolving monasteries and was surrendered to his representatives.

Some of the houses were subsequently converted for private use and the church, which was somewhat damaged during this period with many of the elaborate tombs destroyed, was briefly closed before it and other buildings were given to the City of London Corporation who reopened it again in 1547 as Christ Church Greyfriars, a parish church serving the now joined parishes of St Nicholas Shambles and St Ewen.

Only a few year’s later King Edward IV founded a school for poor orphans in some of the old friary buildings known as Christ’s Hospital or informally as The Bluecoat School thanks to the uniforms students wore. Some of the school buildings, along with part of the church which was also used by the school, was destroyed by the Great Fire of London in 1666, but the school was rebuilt and remained in use until the late 1800s when the last of the students were relocated to a new facility in Sussex (where the school still exists today).

The church (also known as Christ Church Newgate Street), meanwhile, was also rebuilt after the Great Fire – it was one of Sir Christopher Wren’s designs and was completed in 1704. The church remained in use until World War II when a firebomb struck it during a German raid on 29th December, 1940, all but destroying it.

The church (also known as Christ Church Newgate Street), meanwhile, was also rebuilt after the Great Fire – it was one of Sir Christopher Wren’s designs and was completed in 1704. The church remained in use until World War II when a firebomb struck it during a German raid on 29th December, 1940, all but destroying it.

The church was not rebuilt and the parish merged with the nearby St Sepulchre-without-Newgate – the largest parish church in London – and eventually what’s left of the church – the tower with rebuilt steeple and the west and north walls – were converted into a public garden (rose beds were planted where the pews once stood and there are wooden towers representing the church’s pillars). Pictured right, it’s now a terrific place to sit and have lunch pondering the past which the bustle of the city goes on about you.

PICTURE: (top) Wikipedia

For a great biography of Isabella, the She-Wolf of France, see Alison Weir’s Isabella: She-Wolf of France, Queen of England . For more on Sir Christopher Wren’s churches in London, see John Christopher’s Wren’s City of London Churches

. For more on Sir Christopher Wren’s churches in London, see John Christopher’s Wren’s City of London Churches .

.

The second odd Churchill memorial we’re looking at is a clock face located on the facade of Bracken House – a building which sits opposite St Paul’s in the City. The astronomical clock, the work of Philip Bentham, features shows the time, date and astronomical symbol as well as a sunburst at its centre – look closely and you’ll see a familiar face at the centre. The building, which dates from the 1950s, is apparently named after Brendan Bracken, onetime chairman of the Financial Times which was published in the building until the 1980s. The Churchill connection comes in thanks to the fact that Bracken was a close personal friend of Churchill and served as his Minister of Information from 1941 to 1945.

The second odd Churchill memorial we’re looking at is a clock face located on the facade of Bracken House – a building which sits opposite St Paul’s in the City. The astronomical clock, the work of Philip Bentham, features shows the time, date and astronomical symbol as well as a sunburst at its centre – look closely and you’ll see a familiar face at the centre. The building, which dates from the 1950s, is apparently named after Brendan Bracken, onetime chairman of the Financial Times which was published in the building until the 1980s. The Churchill connection comes in thanks to the fact that Bracken was a close personal friend of Churchill and served as his Minister of Information from 1941 to 1945.