Little remains of this priory which once stood on the banks of the River Wandle in Surrey (and is now encompassed in Greater London).

The priory, which was founded as an Augustinian house in the early 12th century, rose to become one of the most influential in all of southern Britain.

The institution was created thanks to Gilbert, the Sheriff of Surrey, Huntington and Cambridge, who was granted the village of Merton by King Henry I. Gilbert came to live in Merton and there established a priory, building a church and small huts on land thought to be located just to the west of where the priory was later located.

The institution was created thanks to Gilbert, the Sheriff of Surrey, Huntington and Cambridge, who was granted the village of Merton by King Henry I. Gilbert came to live in Merton and there established a priory, building a church and small huts on land thought to be located just to the west of where the priory was later located.

Gilbert had been impressed with what he’d seen of the Augustinians, also known as the Austin friars, at Huntington and so gave control of the new church to their sub-prior, Robert Bayle, along with the land and a mill.

It was based on Bayle’s advice that the site of the priory was then moved to its second location and a new, larger wooden chapel built with William Gifford, Bishop of Winchester, coming to bless the cemetery. The canons – there were now 17 – moved in on 3rd May, 1117.

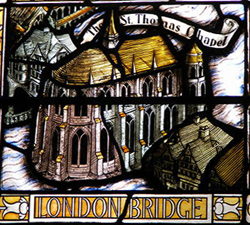

Among the high profile people to visit the new priory was Queen Matilda, who brought her son William with her. In the early 1100s, a certain Thomas Becket (later the ill-fated Archbishop of Canterbury) received an education here as did Nicolas Breakspeare (later the first English Pope, Adrian IV).

The priory expanded considerably over the next century and in 1217 its chapter house was the location of a peace conference between King Henry III and Louis, the Dauphin of France. The Statutes of Merton – a series of legal codes relating to wills – were formulated here in 1236.

The connection with royalty continued – in the mid-1340s, King Edward III is thought to have passed the Feast of the Epiphany here while King Henry VI apparently had a crowning ceremony here – the first outside of Westminster Abbey for more than 300 years – in 1437.

The priory remained in use until the Dissolution of King Henry VIII. The demolition of the buildings apparently started even before the priory had been formally surrendered to the commissioners – stones from its building was used in the construction of Henry’s new palace – Nonsuch – as well as, later, in the construction of local buildings.

The site came to be referred to as ‘Merton Abbey’ and, passing through various hands, was used to garrison Parliamentarian troops during the Civil War. It later became a manufacturing facility, works for the dying and printing of textiles, one of which became the workshops of William Morris.

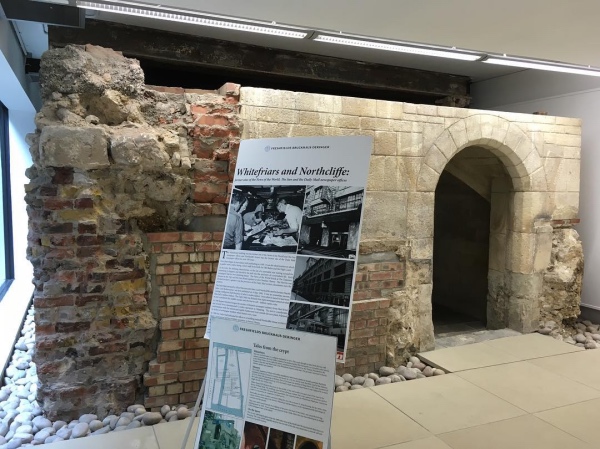

Some of the priory buildings survived for some years after but the only remains now left as sections of the perimeter wall (the arch which now stands over the entrance to Merton parish church is reconstructed – there’s another ornamental gateway in the outer court wall which was also replaced with a replica in the 1980s).

The foundations of the unusually large chapter house, meanwhile, have been excavated and are now preserved in a specially constructed enclosure under a roadway. Construction is now underway to build better public access to the remains.

PICTURE: A ceiling boss from Merton Priory which still bears traces of its original red paint and guilding. It was found during excavations at Nonsuch Palace in 1959-60 is now on display in the Museum of London. Photograph by Mike Peel (www.mikepeel.net) (licensed under CC-BY-SA-4.0).