While the designation of London’s oldest public library depends on your definition, for the purposes of this article we’re awarding the title to the Guildhall Library.

Its origins go back to about 1425 when town clerk John Carpenter and John Coventry founded a library – believed to initially consist of theological books for students, according to the terms of the will of former Lord Mayor, Richard (Dick) Whittington (for more on him, see our previous post here).

Housed in Guildhall (pictured above), this library apparently came to an end in the mid-1500s when Edward Seymour, the Duke of Somerset and Lord Protector for the young King Edward VI, apparently had the entire collection loaded onto carts and taken to Somerset House. They were not returned and only one of the library’s original texts, a 13th century metrical Latin version of the Bible, is in the library today.

Housed in Guildhall (pictured above), this library apparently came to an end in the mid-1500s when Edward Seymour, the Duke of Somerset and Lord Protector for the young King Edward VI, apparently had the entire collection loaded onto carts and taken to Somerset House. They were not returned and only one of the library’s original texts, a 13th century metrical Latin version of the Bible, is in the library today.

Some 300 years passed until the library was re-established by the City of London Corporation. Reopened in 1828, it was initially reserved for members of the Corporation but the membership was soon expanded to include”literary men”.

By the 1870s, when the collection included some 60,000 books related to London, the library moved into a new purpose-built building, located to the east of Guildhall. Designed by City architect Horace Jones, it opened to the public in 1873.

The library lost some 25,000 books during World War II when some of the library’s storerooms were destroyed and after the war, it was decided to build a new library. It opened in 1974 in the west wing of the Guildhall where it remains (entered via Aldermanbury).

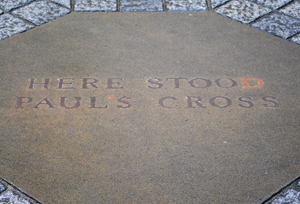

Today, the 200,000 item collection includes books, pamphlets, periodicals including the complete London Gazette from 1665 to the present, trade directories and poll books as well as the archive collections such as those of the livery companies, the Stock Exchange and St Paul’s Cathedral and special collections related to the likes of Samuel Pepys, Sir Thomas More, and the Charles Lamb Society.

The library also holds an ongoing series of exhibitions.

Where: Guildhall Library, Aldermanbury; WHEN: 9.30am to 5pm, Monday to Saturday; COST: Entry is free and no membership of registration is required but ID may be required to access rarer books; WEBSITE: www.cityoflondon.gov.uk/things-to-do/visiting-the-city/archives-and-city-history/guildhall-library/Pages/default.aspx.