This barrel-shaped object, which can be found in the church of All Hallows by the Tower in the City of London, was used the crow’s nest on the ship Quest during Sir Ernest Shackleton’s third – and last – Antarctic voyage in the early 1920s.

George V

This Week in London – The glamour of the Edwardian Royals; tulips at Hampton Court; and, Cartier jewels at the V&A…

• The glamour and opulence of the Edwardian era – and the two royal couples that exemplified it – is the subject of a new exhibition opening at The King’s Gallery at Buckingham Palace tomorrow. The Edwardians: Age of Elegance takes an in-depth look at the lives of King Edward VII and Queen Alexandra, and King George V and Queen Mary, exploring not only their family interactions but their glittering social circles, travel adventures and, of course, the royal events they attended. More than 300 items are on display in the exhibition – almost half on show for the first time – with highlights including Queen Mary’s ‘Love Trophy’ Collar necklace which is on display for the first time, a Cartier crystal pencil case set with diamonds and rubies, and, a blue enamel Fabergé cigarette case featuring a diamond-encrusted snake biting its own tail which was given to King Edward VII in 1908 by his favourite mistress as a symbol of eternal love. There’s also a never-before-seen photograph of Edward wearing fancy-dress as a knight of the Order of Malta as he attended a ball celebrating Queen Victoria’s 1897 Diamond Jubilee, a previously unseen study of Sleeping Beauty by the Pre-Raphaelite artist Sir Edward Burne-Jones, and, Charles Baugniet’s After the Ball which is on show for the first time in more than a century. Runs until 23rd November. Admission charge applies. For more, see www.rct.uk.

• More than 100,000 tulip bulbs are springing to life at Hampton Court Palace for its annual Tulip Festival. The display includes an installation of 10,000 tulips in the palace’s Fountain Court, floating tulip bowls in the Great Fountain, a vintage horse cart spilling tulips in the Clock Court, free-style planting, inspired by the tulip fields of the Netherlands, in the Kitchen Garden and rare, historic and specialist varieties of tulips in the Lower Orangery. There will be daily “tulip talks” in the palace’s wine cellar exploring the history of the flower and how Queen Mary II introduced them to the palace. Runs from Friday until 5th May. Included in general admission. For more, see www.hrp.org.uk.

• The first major exhibition in 30 years dedicated to Cartier jewels and watches opens at the V&A this Saturday. Cartier, which is being held in The Sainsbury Gallery, charts the rise of the globally recognised jewellery house and how it became known as “the jeweller of kings and the king of jewellers”. The display features more than 350 objects with highlights including the Williamson Diamond brooch which was commissioned by Queen Elizabeth II in 1953 and which features the rare 23.6 carat pink Williamson diamond; the Scroll Tiara commissioned in 1902 and worn to the coronation of Elizabeth II and later by Rihanna on the cover of W magazine in 2016; Grace Kelly’s engagement ring (1956) that she wore in her final film High Society; Mexican film star María Félix’s snake necklace (1968); and, a selection of Cartier timepieces that embody its pioneering approach to watchmaking, including the Crash wristwatch, designed by Cartier London (1967). The exhibition runs until 16th November. Admission charge applies. For more, see vam.ac.uk/exhibitions/cartier.

Send all items to exploringlondon@gmail.com.

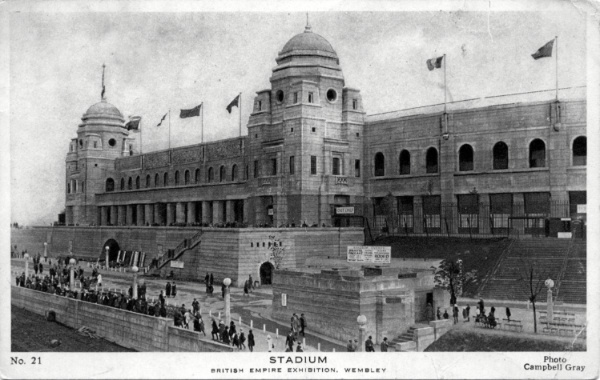

A Moment in London’s History – The British Empire Exhibition…

It’s 100 years ago this year that the British Empire Exhibition was held in Wembley Park.

Located on a more than 200 acre site, the exhibition was designed to showcase the diversity and reach of the empire. It ran for two six-month long summer seasons – first opening on 23rd April, 1924, and running until 1st November that year and then reopening on 9th May, 1925, and running until 1st October.

The opening ceremony, which took place on St George’s Day, was attended by King George V and Queen Mary, and the event, in a first for a monarch, was broadcast on BBC radio.

The exhibition, which cost £12 million and attracted some 27 million visitors, featured what was said to be the largest sports arena in the world – Empire Stadium (later known as Wembley Stadium) – as well as four main pavilions dedicated to industry, engineering, the arts and the government, and a series of pavilions for 56 of the empire’s 58 territories as well as some commercial pavilions.

The latter included an Indian pavilion modelled on Jama Masjid in Delhi and the Taj Mahal in Agra, a West African pavilion designed to look like an Arab fort, a Burmese pavilion designed to look like a temple and a Maltese pavilion designed as a fortress with the entrance resembling the famed Mdina Gate.

The Empire Stadium hosted events including military tattoos and Wild West rodeos while other attractions included a lake, a 47 acre fairground, a garden, restaurants and a working replica coal mine.

Star attractions included a replica of King Tutankhamen’s tomb (housed in the fairground), a working model of Niagara Falls and a full-sized sculpture of the Prince of Wales (later Edward VIII) made of butter (both in the Canadian pavilion), a 16 foot diameter ball of wool (Australian pavilion) and dodgem cars (also in the funfair). Queen Mary’s Dollhouse – now housed at Windsor – was designed by Sir Edwin Lutyens and served as a miniature showcase of the finest goods of the period.

Reinforced concrete was the main building material used in its construction, earning it the title of the first “concrete city”. The streets of the exhibition, meanwhile, were named by Rudyard Kipling.

Wembley Park Tube station, which had first opened in 1893, was rebuilt for the event and a new station – Exhibition Station (Wembley) added (it was officially closed in 1969).

While many of the buildings were dismantled after the exhibition, some survived for decades afterwards including, of course, the Empire Stadium which became Wembley Stadium and was the home of English football until replaced in 2003.

Treasures of London – Russell Street gas lamps…

Recently listed as Grade II, these four gas lamps on Russell Street in Westminster were among a series of lamps installed around Covent Garden to mark the beginning of King George V’s reign.

While the columns of the lamps date from 1910, three of the lanterns – described as an ‘Upright Rochester lantern’ and manufactured by William Sugg and Company Limited – are replacements believed to have been installed around 1930. The fourth was installed following a campaign to save Covent Garden from redevelopment in the 1970s.

The newly listed lamp-posts – the first Westminster lamps to be listed in 40 years – are located outside numbers 4-6, 24, 29, and 34-43.

There are currently about 1,300 working gas lamps in London, around 270 of which are in Westminster (and about half of which are listed).

10 atmospheric ruins in London – 2. St George’s Garrison Church…

This mid-18th century church in Woolwich was constructed to serve the soldiers of the Royal Artillery but was badly damaged when hit by a bomb during World War II.

Designed by Thomas Henry Wyatt with the aid of his younger brother, Matthew Digby Wyatt, in the style of an Early Christian/Italian Romanesque basilica, the church was built between 1862 and 1863 on the orders of Lord Sidney Herbert, the Secretary of State for War.

It was among a number of buildings built to provide for the well-being of soldiers after a public outcry about their living conditions during the Crimean War.

The interior featured lavish decoration including mosaics said to have been based on those found in Roman and Byzantine monuments in Ravenna, Italy. Those that survive at the church’s east end – which include one of St George and the Dragon and others featuring a peacock and phoenix – are believed to have been made in Venice in the workshop of Antonio Salviati.

The mural of St George formed part of a memorial to the Royal Artillery’s Victoria Cross recipients located in the church and paid for through public subscription in 1915. The interior also featured five tall stained glass windows which served as memorials to fallen officers.

Plaques on the perimeter walls record the names of soldiers killed in military conflict or Royal Artillery servicemen who died of natural causes.

The church was visited by King George V and Queen Mary in 1928.

The church, which had survived a bombing in World War I, was largely destroyed on 13th July, 1944, when it was hit by a V1 flying bomb. Most of the interior was gutted in the fire that followed.

While plans to rebuild it after World War II were shelved, in 1970 it became a memorial garden with a roof placed over the church’s east end to protect the mosaics.

Services are still held in the Grade II-listed ruin, located opposite the Woolwich Barracks, and since 2018 it has been under the care of the Woolwich Garrison Church Trust.

WHERE: St George’s Garrison Church, A205 South Circular, Grand Depot Road, Woolwich (nearest DLR station is Woolwich Arsenal); WHEN: 10am to 1pm Sundays (October to March) and 10am to 4pm Sundays (April to September); COST: Free; WEBSITE: https://www.stgeorgeswoolwich.org.

Note that we’ve changed the title of this special series to allow us to explore a bit wider than the medieval period alone!

Four sites related to royal coronations in London – 1. The Jewel House…

In the lead-up to the coronation of King Charles III and Queen Consort Camilla on 6th May, we’re taking a look at sites in London which have played an important role in coronations past (and, mostly, in this coronation as well).

First up, it’s the Tower of London’s Jewel House which is linked to the coronation through the role it plays in housing the Crown Jewels and, more specifically, the Coronation Regalia.

The centrepiece of the Crown Jewels is St Edward’s Crown, with which King Charles will be crowned in Westminster Abbey.

The crown, which has already been removed from the Tower of London so it could be resized for the occasion, is made from 22 carat gold and adorned with some 444 precious and semi-precious gems. Named for St Edward the Confessor, it dates from 1661 when it was made for the coronation of King Charles II and replaces an earlier version melted down after Parliament abolished the monarchy in 1649.

The crown was subsequently used in 1689 in the coronation of joint monarchs King William III and Queen Mary II and then not used again until 1911 when as used to crown King George V. It was also used to crown King George VI and Queen Elizabeth II in 1953.

St Edward’s Crown is not the only crown that will be used in the coronation ceremony – the King will also wear the Imperial State Crown at the end of the service.

Made by Garrard and Company for the coronation of King George VI in 1937 (replacing a crown made for Queen Victoria in 1838), it features the Black Prince’s Ruby in the front – said to have been a gift to Edward, the Black Prince, in 1357 from the King of Castile.

Further gems in the crown include the Stuart Sapphire, the Cullinan II Diamond and St Edward’s Sapphire, said to have been worn in a ring by St Edward the Confessor and found in his tomb in 1163.

Among other items which will be used in the coronation are the Sovereign’s Sceptre with Cross, the Sovereign’s Orb, and the Coronation Spoon.

The sceptre was made for King Charles II and now features the world’s largest diamond, the Cullinan Diamond, which was added to it in 1911. The orb was also made for King Charles II’s coronation and is topped with a cross.

The spoon, meanwhile, is one of the oldest items in the Crown Jewels, dating from the 12th century. It is used for anointing the new sovereign with holy oil – which comes from the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem – during the ceremony. It survived the abolition of the monarchy after it was purchased by a member of King Charles I’s wardrobe and later returned to King Charles II after the monarchy. The oil is held in a golden vessel known as an ampulla which is shaped like an eagle.

Other items to be used in the coronation are a series of swords – among them the Sword of State, the Sword of Temporal Justice, the Sword of Spiritual Justice, and the Sword of Mercy (this has its tip blunted to represent the Sovereign’s mercy).

The regalia was housed at Westminster Abbey until 1649. They have been kept at the Tower of London since the Restoration (even surviving a theft attempt by Colonel Thomas Blood and accomplices in 1671).

The Crown Jewels, which are now held under armed guard, have been housed in several different locations during their time at the Tower of London including in the Martin Tower and the Wakefield Tower. They were moved into a subterranean vault in the western end of the Waterloo Block (formerly the Waterloo Barracks), now known as the Jewel House (and not to be confused with The Jewel Tower in Westminster), in 1967.

A new Jewel House was opened by Queen Elizabeth II on the ground floor of the former barracks in 1994. The exhibit was revamped in 2012 and following King Charles III’s coronation, the display is again being transformed with a new exhibition exploring the origins of some of the objects for the first time.

WHERE: The Jewel House, Tower of London (nearest Tube station Tower Hill); WHEN: 9am to 4.30pm (last admission), Tuesday to Saturday, 10am to 4.30pm (last admission) Sunday to Monday; COST: £29.90 adults; £14.90 children 5 to 15; £24 concessions (family tickets available; discounts for online purchases/memberships); WEBSITE: https://www.hrp.org.uk/tower-of-london/whats-on/the-crown-jewels/.

Special – Lying in state at Westminster Hall…

The tradition of lying in state – whereby the monarch’s coffin is placed on view to allow the public to pay their respects before the funeral – at Westminster Hall isn’t actually a very old one.

The first monarch to do so was King Edward VII in 1910. The idea had come from the previous lying-in-state of former Prime Minister William Ewart Gladstone who had lain in state following his death in 1898.

Ever since then, every monarch, with the exception of King Edward VIII, who had abdicated, has done so along with other notable figures including Queen Mary, wife of King George V, in 1953, former Prime Minister Sir Winston Churchill in 1965, and Queen Elizabeth, the Queen Mother, for a three day period in 2002 when some 200,000 people paid their respects.

During the lying-in-state period (which members of the public may pay their respects), the coffin is placed on a central raised platform, known as a catafalque, and each corner of the platform is guarded around the clock by units from the Sovereign’s Bodyguard, Foot Guards or the Household Cavalry Mounted Regiment. The coffin is draped with the Royal Standard and placed on top is the Orb and Sceptre.

Westminster Hall, the oldest surviving building in the Palace of Westminster and the only part which survives almost in original form, was constructed between 1097 and 1099 on the order of King William (Rufus) II.

Measuring 240 by 67 feet and covering some 17,000 square feet, at the time it was the largest hall in England and possibly the largest in Europe (although once anecdote has the King, when an attendant remarked on its size, commenting that it was a mere bedchamber compared to what he’d had in mind).

Since then, it has been used for a range of purposes including coronation banquets – the earliest recorded is that of Prince Henry, the Young King, son of King Henry II and King Henry’s other son, King Richard the Lionheart, other feasts and banquets – including in 1269 to mark the placing of Edward the Confessor’s remains in the new shrine in Westminster Abbey, and for political events and gatherings such as in 1653 when Oliver Cromwell took the oath as Lord Protector.

It has also been the location of law courts (the trial of William Wallace was held here in 1305 and that of King Charles I in 1649) and even shops.

10 (lesser known) statues of English monarchs in London…4. King Edward VII…

It’s a rather incongruous place for a king. Standing outside the entrance to Tooting Broadway Underground Station is a large-than-life statue of King Edward VII, who ruled from 1901-1910.

Erected in 1911 after the King’s death, the statue is the work of Louis Fritz Roselieb (later Roslyn) and was funded through a public subscription.

The statue depicts the King in royal regalia holding a sceptre in his right hand with his left hand resting on his sword hilt. The plinth features bronze reliefs on either side depicting representations of ‘peace’ and ‘charity’.

Given Tooting Broadway Underground Station didn’t open until 1926, the statue wasn’t initially located in relation to it.

In fact, it was originally located on a traffic island a short distance from its current siting but was moved after the area was remodelled in 1994.

It isn’t, of course the only statue of King Edward VII in London – the more well known one can be found in Waterloo Place. It was unveiled by his son, King George V, in 1921.

Where’s London’s oldest…embassy?

Another ‘oldest’ question that’s not as simple as it might seem.

Austria has occupied a building at 18 Belgrave Square in Belgravia since it moved there from Chandos House in Queen Anne Street in 1866.

But the embassy was vacated with the outbreak of World War I and the building entrusted, firstly to the protection of the ambassador of the United States, and following the severing of their relations in 1917, to the Royal Swedish Legation.

The Austrians returned in 1920 but following Hitler’s incorporation of Austria into the German Reich in 1938, it was used as a department of the German Embassy.

Following the outbreak of World War II, the Swiss legation room over protection of the building and following the end of the war the damaged building fell under the care of Britain’s Ministry of Works.

The Austrians returned in September, 1948, with the new ambassador arriving in 1952. It continues today to serve as the residence of the Austrian Ambassador.

Not to be confused with the Austrians, the Australian High Commission resides in ‘Australia House’ which claims to be “the longest continuously occupied foreign mission in London”.

In 1912, the Australian Government bought the freehold of a site on the corner bounded by Strand, Aldwych and Melbourne Place. Following a design competition, Scottish architects A Marshal Mackenzie and Son were selected as the designers of the new Australia House with Commonwealth of Australia’s chief architect, Mr JS Murdoch, arriving in London to assist them.

Work began in 1913 – King George V laid the foundation stone – but was interrupted by World War I and in 1916, former Australian PM and now High Commissioner Andrew Fisher moved into temporary offices on the site even as the work continued around him. King George V officially opened Australia House on 3rd August, 1918, with then Australian Prime Minister, WM “Billy” Hughes, in attendance.

Treasures of London – Southwark Bridge…

Southwark Bridge celebrated its 100th birthday earlier this month so we thought it a good time to have a quick look at the bridge’s history.

The bridge was a replacement for an earlier three-arch iron bridge built by John Rennie which had opened in 1819.

Known by the nickname, the “Iron Bridge”, it was mentioned in Charles Dickens’ Our Mutual Friend and Little Dorrit. But the bridge had problems – its narrow approaches and steep gradient led it to become labelled “the curse of the carman [cart drivers] and the ruin of his horses”.

Increasing traffic meant a replacement became necessary and a new bridge, which featured five arches and was made of steel, was designed by architect Sir Ernest George and engineer Sir Basil Mott.

Work on the new bridge – which was to cost £375,000 and was paid for by the City of London Corporation’s Bridge House Estates which was originally founded in 1097 to maintain London Bridge and expanded to care for others – began in 1913 but its completion was delayed thanks to the outbreak of World War I.

The 800 foot long bridge was finally officially opened on 6th June, 1921, by King George V who used a golden key to open its gates. He and Queen Mary then rode over the bridge in a carriage.

The bridge, now Grade II-listed, was significantly damaged in a 1941 air raid and was temporarily repaired before it was properly restored in 1955. More recently, the bridge was given a facelift in 2011 when £2.5 million was spent cleaning and repainting the metalwork in its original colours – yellow and ‘Southwark Green’.

The current bridge has appeared in numerous films including 1964’s Mary Poppins and, in more recent times, 2007’s Harry Potter and the Order of the Phoenix.

Famous Londoners – Thomas Crapper…

One of the most famous plumbers in the world, Thomas Crapper was the founder of London-based sanitary equipment company, Thomas Crapper & Co, and a man whose name has become synonymous with toilets (although he was not, contrary to popular belief, the inventor of the flushing toilet).

Crapper was born in the town of Thorne in Yorkshire in 1836, the son of Charles Crapper, a sailor (his exact birthday is unknown but he was baptised on 28th September, so it’s thought to have been around that time).

In 1853, he was apprenticed to his brother George, a master plumber based in Chelsea, and, having subsequently gained his own credentials, established himself as a sanitary engineer in Marlborough Road in 1861 (he had married his cousin, Maria Green, the previous year).

Sometime in the late 1860s, in a move some saw as scandalous, his company became the first to open public showrooms displaying sanitary-related products. He was also a strong advocate for the installation of flushing toilets in private homes.

While not the inventor of the modern flushing toilet (that is often credited to Sir John Harington, godson of Queen Elizabeth I, in 1595, although there are even earlier examples), he was responsible for a number of advances in the field including making design improvements to the floating ballcock, a tank-filling mechanism, and the U-bend, an improvement on the S-bend.

Crapper’s company did have some high profile clients – in the 1880s it supplied the plumbing at Sandringham House in Norfolk for then Prince Albert (later King Edward VII). This resulted in Crapper’s first Royal Warrant and the company would go on to receive others from both Albert, when king, and King George V.

Crapper’s branded manhole covers, meanwhile, can still be seen in various parts of London, including around Westminster Abbey where he laid drains. His name can also be found on what are said to be London’s oldest public toilets.

Crapper retired in 1904 (his wife had died two years earlier) and the firm passed to his nephew George (son of his plumber brother George) and his business partner Robert Marr Wharam (the firm, Thomas Crapper & Company, continues to this day – now based in Huddersfield, it still sells a range of vintage bathroom products).

Having spent some time commuting from Brighton, Thomas lived the last six years of his life at 12 Thornsett Road, Anerley, in south-east London (the house now bears a plaque). He died on 27th January, 1910, of colon cancer and was buried at Elmer’s End Cemetery nearby.

While it is often claimed that it’s thanks to Thomas Crapper and his toilets that the word ‘crap’ came to mean excrement, the word is actually of Middle English origin and was already recorded as being associated with human waste when Crapper was just a young boy.

But there is apparently more truth to the claim that toilets became known as ‘crappers’ thanks to Thomas Crapper’s firm. It was apparently American servicemen who, when stationed overseas during World War I, encountered Crapper’s seemingly ubiquitous branding on toilets in England and France and, as a result, started referring to toilets as such.

Where’s London’s oldest…cheesemonger?

With origins dating back to a cheese stall established by Stephen Cullum in Aldwych in 1742, Paxton & Whitfield are generally said to be the oldest cheesemongers still operating in London (and one of the oldest in the UK).

Cullum’s business was successful enough that in the 1770s he opened a shop in Swallow Street. By 1790 his son Sam had taken over the business and took two new partners – Harry Paxton and Charles Whitfield.

In 1835 – with Swallow Street demolished to make way for the construction of Regent Street – Sam moved the business to new premises at 18 Jermyn Street (Sam died the following year).

In 1850, the business received the Royal Warrant of Queen Victoria and just three years later finally settled on the name Paxton and Whitfield which the company still bears to this day.

In 1896, the business moved to its current premises at 93 Jermyn Street and a flurry of Royal Warrants followed – that of King Edward VII in 1901, King George V in 1910, King George VI in 1936, Queen Elizabeth, the Queen Mother in 1972, Prince Charles in 1998 and Queen Elizabeth II in 2002.

The firm, meanwhile, has since passed through several hands but continued on at the same premises (albeit becoming, during the period between the two World Wars, an ordinary grocery shop due to the lack of supply of eggs, butter and cheese).

Business picked up after World War II and the company opened shops in Stratford-upon-Avon and Bath. In 2009 formed a partnership with Parisian cheese mongers, Androuet, and in 2014 it opened a new shop in Cale Street, Chelsea.

For more, see www.paxtonandwhitfield.co.uk.

PICTURE: Herry Lawford (licensed under CC BY 2.0)

A Moment in London’s History – The opening of Tower Bridge…

This year marks 125 years since the opening of Tower Bridge.

The bridge, which took eight years to build and was designed by City of London architect Sir Horace Jones in collaboration with engineer Sir John Wolfe Barry, was officially opened on 30th June, 1894, by the Prince and Princess of Wales (the future King Edward VII and Queen Alexandra).

Others among the tens of thousands who turned out to mark the historic event were the Duke of York (later King George V), Lord Mayor of London Sir George Robert Tyler and members of the Bridge House Estates Committee.

A procession of carriages carrying members of the royal family had set out from Marlborough House that morning, stopping at Mansion House on its way to the bridge.

Once there, it drove back and forth across before official proceedings took place in which the Prince of Wales pulled a lever to set in motion the steam-driven machinery which raised the two enormous bascules and allowed a huge flotilla of craft of all shapes and sizes to pass under it.

The event was also marked with a gun salute fired from the Tower of London.

Plaques commemorating the opening can be found at either end of the bridge. The event was also captured in a famous painting by artist William Lionel Wyllie who had attended with his wife. The painting is now held at the Guildhall Art Gallery.

Tower Bridge has been running a series of special events to mark the anniversary this year. For more, see www.towerbridge.org.uk.

Tower Bridge today. PICTURE: Charles Postiaux/Unsplash

This Week in London – Queen Victoria at Buckingham Palace; royal etchings; and, Ed Ruscha at Tate Modern…

• The impact of Queen Victoria on Buckingham Palace, transforming what was empty residence into “the most glittering court in Europe”, is a special focus of this year’s summer opening of Buckingham Palace. Marking the 200th anniversary of the birth of the Queen, the exhibition Queen Victoria’s Palace recreates the music, dancing and entertaining that characterised the early part of the Queen’s reign using special effects and displays. Highlights include the Queen’s costume (pictured) for the Stuart Ball of 13th July, 1851, where attendees dressed in the style of King Charles II’s court. There’s also a recreation of a ball held in the palace’s newly completed Ballroom and Ball Supper Room on 17th June, 1856, to mark the end of the Crimean War and honour returning soldiers which uses a Victorian illusion technique known as Pepper’s Ghost to bring to life Louis Haghe’s watercolour, The Ball of 1856. The table in the State Dining Room, meanwhile, has been dressed with items from the ‘Victoria’ pattern dessert service, purchased by the Queen at the 1851 Great Exhibition, and the room also features the Alhambra table fountain, a silver-gilt and enamel centrepiece commissioned by Victoria and Albert in the same year, and silver-gilt pieces from the Grand Service, commissioned by the Queen’s uncle, King George IV, on which sit replica desserts based on a design by Queen Victoria’s chief cook, Charles Elme Francatelli. The summer opening runs until 29th September. Admission charges apply. For more, see www.rct.uk/visit/the-state-rooms-buckingham-palace. PICTURE: Royal Collection Trust/ © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2019

• The impact of Queen Victoria on Buckingham Palace, transforming what was empty residence into “the most glittering court in Europe”, is a special focus of this year’s summer opening of Buckingham Palace. Marking the 200th anniversary of the birth of the Queen, the exhibition Queen Victoria’s Palace recreates the music, dancing and entertaining that characterised the early part of the Queen’s reign using special effects and displays. Highlights include the Queen’s costume (pictured) for the Stuart Ball of 13th July, 1851, where attendees dressed in the style of King Charles II’s court. There’s also a recreation of a ball held in the palace’s newly completed Ballroom and Ball Supper Room on 17th June, 1856, to mark the end of the Crimean War and honour returning soldiers which uses a Victorian illusion technique known as Pepper’s Ghost to bring to life Louis Haghe’s watercolour, The Ball of 1856. The table in the State Dining Room, meanwhile, has been dressed with items from the ‘Victoria’ pattern dessert service, purchased by the Queen at the 1851 Great Exhibition, and the room also features the Alhambra table fountain, a silver-gilt and enamel centrepiece commissioned by Victoria and Albert in the same year, and silver-gilt pieces from the Grand Service, commissioned by the Queen’s uncle, King George IV, on which sit replica desserts based on a design by Queen Victoria’s chief cook, Charles Elme Francatelli. The summer opening runs until 29th September. Admission charges apply. For more, see www.rct.uk/visit/the-state-rooms-buckingham-palace. PICTURE: Royal Collection Trust/ © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2019

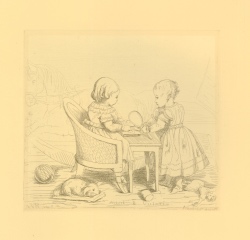

• The Victorian reign is also the subject of a new exhibition at the British Museum where rare etchings by Queen Victoria and Prince Albert have gone on display. At home: Royal etchings by Queen Victoria and Prince Albert features 20 artworks that they created during the early years of their marriage and depict scenes of their domestic lives at Windsor Castle and Claremont including images of their children and pets. The display includes three works donated to the museum by King George V, Queen Victoria’s grandson, in 1926, and it’s the first time they’ve gone on public display. Prince Albert introduced the Queen to the practice of etching soon after their wedding and under the guidance of Sir George Hayter they made their first works on 28th August, 1840. They would go on to collaborate on numerous works together. The display can be seen in Room 90a until mid-September. Admission is free. For more, see www.britishmuseum.org. PICTURE: The Princess Royal and Prince of Wales, 1843, by Albert, Prince Consort (after Queen Victoria) © The Trustees of the British Museum.

• The Victorian reign is also the subject of a new exhibition at the British Museum where rare etchings by Queen Victoria and Prince Albert have gone on display. At home: Royal etchings by Queen Victoria and Prince Albert features 20 artworks that they created during the early years of their marriage and depict scenes of their domestic lives at Windsor Castle and Claremont including images of their children and pets. The display includes three works donated to the museum by King George V, Queen Victoria’s grandson, in 1926, and it’s the first time they’ve gone on public display. Prince Albert introduced the Queen to the practice of etching soon after their wedding and under the guidance of Sir George Hayter they made their first works on 28th August, 1840. They would go on to collaborate on numerous works together. The display can be seen in Room 90a until mid-September. Admission is free. For more, see www.britishmuseum.org. PICTURE: The Princess Royal and Prince of Wales, 1843, by Albert, Prince Consort (after Queen Victoria) © The Trustees of the British Museum.

• American artist Ed Ruscha is the subject of the latest “Artist Rooms” annual free display in the Tate Modern’s Blavatnik building on South Bank. The display features works spanning Ruscha’s six-decade career, including large, text-based paintings and his iconic photographic series. There is also a display of Ruscha’s artist’s books – including Various Small Fires 1964 and Every Building on the Sunset Strip 1966 – as well as some 40 works on paper gifted to Tate by the artist. Highlights include his series of photographs of LA’s swimming pools and parking lots, paintings inspired by classic Hollywood cinema, and works such as DANCE? (1973), Pay Nothing Until April (2003) and Our Flag (2017). Runs until spring 2020. Admission is free. For more, see www.tate.org.uk.

Send all items for inclusion to exploringlondon@gmail.com.

Eight historic department stores in London…7. Hamleys…

This Regent Street establishment – the oldest and largest toy store in the world – dates back to 1760 when Cornishman William Hamley came to London and founded his toy store – then called ‘Noah’s Ark’ – on High Holborn.

This Regent Street establishment – the oldest and largest toy store in the world – dates back to 1760 when Cornishman William Hamley came to London and founded his toy store – then called ‘Noah’s Ark’ – on High Holborn.

Selling everything from wooden hoops to tin soldiers and rag dolls, the business aimed to capture the trade of affluent Bloomsbury families and proved rather successful, attracting a clientele in the early 19th century which included not only wealthy families but royalty.

Such was its success that in 1881, Hamley’s descendants opened a new branch of the shop at 200 Regent Street. The Holborn store, meanwhile, burned down in 1901 and was subsequently relocated to a larger premises at numbers 86-87 in the same street.

Faced with the Depression in the 1920s, the shop closed briefly in 1931 but was soon reopened by Walter Lines, chairman of Tri-ang Toys, and in 1938 was given a Royal Warrant by Queen Mary, consort of King George V.

The premises at 188-196 Regent Street was bombed five times during the Blitz but the shop (and its tin hat-wearing staff survived). In 1955, having presented a Grand Doll’s Salon and sizeable model railway at the 1951 Festival of Britain, the shop was given a second Royal Warrant – this time by Queen Elizabeth II, who has been given Hamleys toys as a child – as a ‘toys and sports merchant’.

The business, which has passed through several owners since the early 2000s, is now owned by Chinese-based footwear retailer C.banner. The flagship store is spread over seven floors and tens of thousands of toys on sale, located in various departments.

As well as the Regent Street premises (it moved into the current premises at number 188-196 Regent Street in 1981), Hamlets has some 89 branches located in 23 countries, from India to South Africa. A City of Westminster Green Plaque was placed on the store in February 2010, in honour of the business’s 250th anniversary.

The toy store holds an annual Christmas parade in Regent Street which this year featured a cast of 400 and attracted an estimated 750,000 spectators.

PICTURED: Hamleys during its 250th birthday celebrations.

Where’s London’s oldest…public clock (with a minute hand)?

We reintroduce an old favourite this month with our first ‘Where’s London’s oldest’ in a few years. And to kick it off, we’re looking at one of London’s oldest public clocks.

Hanging off the facade of the church of St Dunstan-in-the-West in Fleet Street is a clock which is believed to have been the first public clock to be erected in London which bears a minute hand.

The work of clockmaker Thomas Harris, the clock was first installed on the medieval church in 1671 – it has been suggested it was commissioned to celebrate the church’s survival during the Great Fire of London and was installed to replace an earlier clock which had been scorched in the fire. Its design was apparently inspired by a clock which had once been on Old St Paul’s Cathedral and was destroyed in the fire.

Like the clock it replaced, this clock sat in brackets and projected out into Fleet Street which meant it was able to be seen from a fair distance away (and being double-sided meant the black dials could be seen from both the east and the west). Like the Roman numerals that decorate it, the two hands, including the famous minute hand, are gold.

To the rear and above the clock dials are located the bells and striking mechanism. The bells are struck on the hours and the quarters by ‘automata’ – Herculean figures, perhaps representing Gog and Magog (although to most they were traditionally simply known as the ‘Giants of St Dunstan’s’), who do so using clubs and turn their heads.

Such was the attention these figures attracted that when the clock was first installed the area became notorious for pick-pockets who apparently went to work on unsuspecting passersby who had stopped to watch the giants at work.

This church was demolished in the early 1800s to allow the widening of Fleet Street and when it was rebuilt in 1830, the clock was absent. Having decided it couldn’t be accommodated in the new design, it had been auctioned off with the art collector, Francis Seymour-Conway, the 3rd Marquess of Hertford, the successful bidder.

He had it installed on his Decimus Burton-designed villa in Regent’s Park and there it remained until 1935 when Lord Rothermere, who had bought the villa in 1930, returned it to the church to mark the Silver Jubilee of King George V.

There are numerous literary references to the clock including in Charles Dickens’ David Copperfield, Thomas Hughes’ Tom Brown’s Schooldays, Oliver Goldsmith’s Vicar of Wakefield and a William Cowper poem.

LondonLife – Richmond Weir and Lock…

Crossing the River Thames just downstream of Richmond and Twickenham Bridge, the Richmond weir and lock complex (actually it’s a half-lock and it also incorporates a footbridge) was built in the early 1890s to maintain a navigable depth of water upstream from Richmond. The Grade II*-listed structure, which is maintained by the Port of London Authority, was formally opened by the Duke of York (later King George V) on 19th May, 1894.

This Week in London – Commemorating the Battle of Jutland; ‘lost’ Egyptian cities; and, new Blue Plaques…

• The largest naval conflict of World War I – the Battle of Jutland – is the subject of a new exhibition opening at the National Maritime Museum in Greenwich tomorrow.  Marking the centenary of the battle, Jutland 1916: WWI’s Greatest Sea Battle explores the battle itself (which claimed the lives of more than 8,500 as the British Grand Fleet met the German High Seas Fleet in what neither side could claim as a decisive victory) as well as its lead-up, aftermath and the experience of those serving on British and German warships through paintings and newspaper clippings, photographs, ship models and plans, sailor-made craft work and medals. Among the objects on display is a 14 foot long shipbuilder’s model of the HMS Queen Mary, which, one of the largest battle cruisers involved,was destroyed with only 18 survivors of the 1,266 crew. Among the personal stories told in the exhibition, meanwhile, is that of boy bugler William Robert Walker, of Kennington, who served on the HMS Calliope and, severely wounded during the battle, was later visited by King George V

Marking the centenary of the battle, Jutland 1916: WWI’s Greatest Sea Battle explores the battle itself (which claimed the lives of more than 8,500 as the British Grand Fleet met the German High Seas Fleet in what neither side could claim as a decisive victory) as well as its lead-up, aftermath and the experience of those serving on British and German warships through paintings and newspaper clippings, photographs, ship models and plans, sailor-made craft work and medals. Among the objects on display is a 14 foot long shipbuilder’s model of the HMS Queen Mary, which, one of the largest battle cruisers involved,was destroyed with only 18 survivors of the 1,266 crew. Among the personal stories told in the exhibition, meanwhile, is that of boy bugler William Robert Walker, of Kennington, who served on the HMS Calliope and, severely wounded during the battle, was later visited by King George V

and presented with a silver bugle by Admiral Sir John Jellicoe (the bugle, pictured, is on display). A series of events will accompany the exhibition which runs until November. Admission is free. For more, see www.rmg.co.uk/national-maritime-museum. PICTURE: © National Maritime Museum, London

• Two ‘lost’ Egyptian cities and their watery fate are the subject of a new exhibition which opens at the British Museum today. Sunken cities: Egypt’s lost worlds is the museum’s first exhibition of underwater discoveries and focuses on the recent discoveries of Thonis-Heracleion and Canopus – submerged at the mouth of the Nile for more than 1,000 years. Among the 300 objects on display are more than than 200 artefacts excavated between 1996 and 2012. Highlights include a 5.4 metre statue of Hapy, a sculpture excavated from Canopus representing Arsine II (the eldest daughter of the Ptolemaic dynasty founder Ptolemy I) who became a goddess after her death, and a stela from Thonis-Heracleion which advertises a royal decree of Pharaoh Nectanebo I concerning taxes. The exhibition runs until 27th November. Admission charge applies. For more, see www.britishmuseum.org.

• New English Heritage Blue Plaques marking the homes of comedian Tommy Cooper and food writer Elizabeth David have been unveiled this month as part of the 150th anniversary of the scheme. Tommy Cooper lived at his former home at 51 Barrowgate Road in Chiswick between 1955 to 1984 and while there entertained fellow comedians such as Roy Hudd, Eric Sykes and Jimmy Tarbuck. Elizabeth David, meanwhile, is the first food writer to ever be commemorated with a Blue Plaque. She lived at the property at 24 Halsey Street in Chelsea for some 45 years until her death in 1992. For more, see www.english-heritage.org.uk/visit/blue-plaques/.

Send all items for inclusion to exploringlondon@gmail.com.

A Moment in London’s History – Birth of a future queen…

Queen Elizabeth II, the oldest British monarch, celebrates her 90th birthday later this month and, although we’ve run a piece on the Queen’s birth before, we thought it only fitting to take a second look at what proved to be a momentous birth.

Queen Elizabeth II, the oldest British monarch, celebrates her 90th birthday later this month and, although we’ve run a piece on the Queen’s birth before, we thought it only fitting to take a second look at what proved to be a momentous birth.

The then Princess Elizabeth (Elizabeth Alexandra Mary) was born at 17 Bruton Street in Mayfair – the London home of her maternal grandparents, the Earl and Countess of Strathmore (they also owned Glamis Castle in Scotland) – at 2.40am on 21st April, 1926.

She was apparently delivered by Caesarian section and the Home Secretary, Sir William Joynson-Hicks, was in attendance to ensure everything was above board (the custom, which has since been dropped, was apparently adopted after what was known as the ‘Warming Pan Scandal’ when, following the birth of Prince James Francis Edward, son of King James II and Queen Mary of Modena, in June, 1688, rumours spread that the baby had been stillborn and replaced by an imposter brought into the chamber inside a warming pan).

The first child of the Prince Albert, the Duke of York (Bertie) and Elizabeth Bowes-Lyon, the Duchess of York (later King George VI and Queen Elizabeth), she was third in line to the throne at her birth but thanks to the abdication of King Edward VIII, became her father’s heir.

The event apparently drew a crowd to the property (although none could yet suspect how important this princess was to become) and among the well-wishers who visited the newborn that afternoon were her paternal grandparents, King George V and Queen Mary, who had apparently been woken at 4am to be informed of the birth of their second grandchild.

The property was to be Princess Elizabeth’s home for the first few months of her life (named after her mother, paternal great-grandmother, Queen Alexandra, and paternal grandmother, Queen Mary, she was christened in the private chapel at Buckingham Palace five weeks after her birth).

The home of her birth and a neighbouring townhouse have both since been demolished and replaced by an office building. A plaque commemorating it as the Queen’s birthplace was installed in the Queen’s Silver Jubilee Year of 1977 and another to mark the Diamond Jubilee in 2012.

The Queen’s birthday will be officially commemorated in June.

PICTURE: Via London Remembers

LondonLife – Australia House’s holy well…

News this week that scientists have confirmed an ancient sacred well beneath Australia House in the Strand (on the corner of Aldwych) contains water fit to drink. The well, believed to be one of 20 covered wells in London, is thought to be at least 900 years old and contains water which is said to come from the now-subterranean Fleet River. Australia’s ABC news was recently granted special access to the well hidden beneath a manhole cover in the building’s basement and obtained some water which was tested and found to be fit for drinking. It’s been suggested that the first known mention of the well – known simply as Holywell (it gave its name to a nearby street now lost) – may date back to the late 12th century when a monk, William FitzStephen, commented about the well’s “particular reputation” and the crowds that visited it (although is possible his comments apply to another London well). Australia House itself, home to the Australian High Commission, was officially opened in 1918 by King George V, five years after he laid the foundation stone. The Prime Minister of Australia, WM “Billy” Hughes, was among those present at the ceremony. The interior of the building has featured in the Harry Potter movies as Gringott’s Bank. PICTURE: © Martin Addison/Geograph.

News this week that scientists have confirmed an ancient sacred well beneath Australia House in the Strand (on the corner of Aldwych) contains water fit to drink. The well, believed to be one of 20 covered wells in London, is thought to be at least 900 years old and contains water which is said to come from the now-subterranean Fleet River. Australia’s ABC news was recently granted special access to the well hidden beneath a manhole cover in the building’s basement and obtained some water which was tested and found to be fit for drinking. It’s been suggested that the first known mention of the well – known simply as Holywell (it gave its name to a nearby street now lost) – may date back to the late 12th century when a monk, William FitzStephen, commented about the well’s “particular reputation” and the crowds that visited it (although is possible his comments apply to another London well). Australia House itself, home to the Australian High Commission, was officially opened in 1918 by King George V, five years after he laid the foundation stone. The Prime Minister of Australia, WM “Billy” Hughes, was among those present at the ceremony. The interior of the building has featured in the Harry Potter movies as Gringott’s Bank. PICTURE: © Martin Addison/Geograph.