Born to humble origins in London, Inigo Jones rose to become the first notable architect in England and, thanks to his travels, is credited with introducing the classical architecture of Rome and the Italian Renaissance to the nation.

Jones came into the world on 15th July, 1573, as the son of a Welsh clothworker, also named Inigo Jones (the origins of the name are apparently obscure), in Smithfield, London. He was baptised in St Bartholomew-the-Less but little else is known of his early years (although he was probably apprenticed to a joiner).

At about the age of 30, Jones is believed to have travelled in Italy – he certainly spent enough time there to be fluid in Italian – and he is also said to have spent some time in Denmark, apparently doing some work there for King Christian IV.

At about the age of 30, Jones is believed to have travelled in Italy – he certainly spent enough time there to be fluid in Italian – and he is also said to have spent some time in Denmark, apparently doing some work there for King Christian IV.

Returning to London, he secured the patronage of King Christian’s sister Queen Anne, the wife of King James I, and became famous as a designer of costumes and stage settings for royal masques (in fact, he is credited with introducing movable scenery to England).

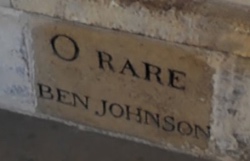

Between 1605 and 1640, he staged more than 500 performances – his first was The Masque of Blackness performed on twelfth night in 1605 – including many collaborations with playwright Ben Jonson with whom he had an, at times, acrimonious relationship.

His architectural work in England – heavily influenced by the Italian architect Andrea Palladio (his copy of Palladio’s Quattro libri dell’architettura is dated 1601) as well as the Roman architect Vitruvius – dates from about 1608 with his first known building design that of the New Exchange in the Strand, built for Robert Cecil, 1st Earl of Salisbury.

In 1611 Jones was appointed surveyor of works to Henry Frederick, the Prince of Wales, but, following the prince’s death on 6th November, 1612, he was, in 1615, appointed Surveyor of the King’s Works (having first accompanied Thomas Howard, the 2nd Earl of Arundel, on what would be his second visit to Italy).

Jones’ big break came in 1615 when he was made Surveyor-General of the King’s Works, a post he would hold for 27 years. He was subsequently was responsible for the design and building of the Queen’s House in Greenwich for Queen Anne (started in 1616 and eventually completed in 1635), the Banqueting House in Whitehall (built between 1619 and 1622, it’s arguably his finest work), the Queen’s Chapel in St James’s Palace (1623 to 1627) and, in 1630, Covent Garden square for the Earl of Bedford including the church of St Paul’s, Covent Garden.

Other projects included the repair and remodelling of parts of Old St Paul’s Cathedral prior to its destruction in 1666 and a complete redesign of the Palace of Whitehall (which never went ahead). He’s also credited with assisting other architects on numerous other jobs.

Jones’ career – both as an architect and as a producer of masques – stopped rather abruptly with the outbreak of the Civil War in 1642 and the subsequent seizing of the king’s properties. Forced to leave London, he was eventually captured by Parliamentarians following a siege at Basing House in Hampshire in October, 1645.

His property was initially confiscated and he was heavily fined but he was later pardoned and his property returned.

Never married, Jones ended up living in Somerset House in London and died on 21st June, 1652. He was buried with his parents at St Benet Paul’s Wharf. A rather elaborate monument to his memory erected inside the church was damaged in the Great Fire of 1666 and later destroyed.

Jones’ legacy can still be seen at various sites around London where his works survive and also in the works of those he influenced, including Richard Boyle, 3rd Earl of Burlington, designer and builder of Chiswick House, and architect and landscape designer William Kent.

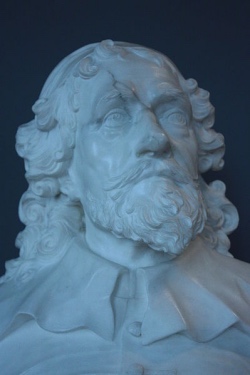

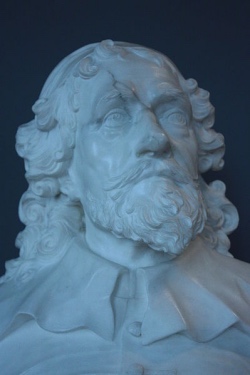

PICTURE: Bust of Inigo Jones by John Michael Rysbrack, (1725) (image by Stephencdickson/licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0)