It was 360 years ago late last month that the body of Oliver Cromwell, one time Lord Protector of the Commonwealth, was, having previously been exhumed from his grave in Westminster Abbey, hanged from a gallows at Tyburn before being beheaded.

Cromwell had died two years previously on 3rd September, 1658, at the age of 59. It’s thought he died of septicaemia brought on by a urinary infection (although the death of his favourite daughter Elizabeth a month before is also believed to have been a significant factor in his own demise).

He (and his daughter) were buried in an elaborate funeral ceremony in a newly created vault in King Henry VII’s chapel at Westminster Abbey.

Cromwell’s son Richard had succeeded him as Lord Protector but he was forced to resign in May, 1659, and divisions among the Commonwealth’s leadership soon saw Parliament restored and the monarchy restored under King Charles II in 1660.

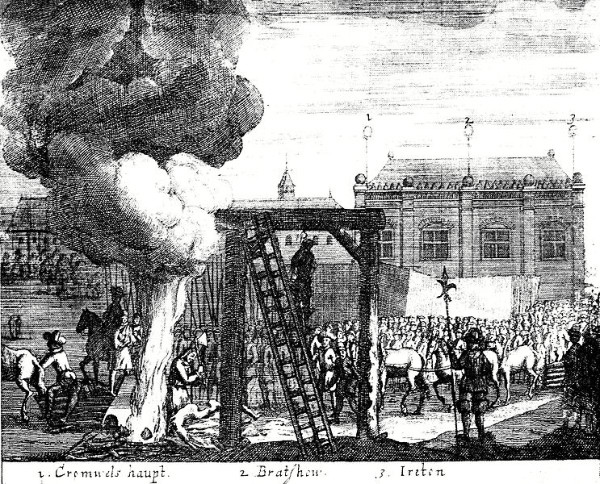

In late January, 1661, on Parliament’s order, Cromwell’s body as well as those of John Bradshaw, President of the High Court of Justice for the trial of King Charles I, and Henry Ireton, Cromwell’s son-in-law and a general in the Parliamentary army during the English Civil War, were all exhumed from their graves.

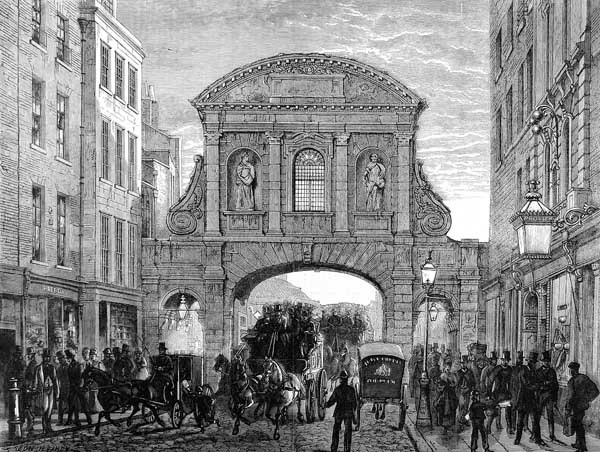

The bodies of Cromwell and Ireton were taken to the Red Lion Inn in Holborn where they lay under guard overnight and were joined by that of Bradshaw the following day.

That morning – the 30th January, a date which coincided with the 12th anniversary of the execution of King Charles I in 1649 – the shrouded bodies in various states of decomposition and laying in open coffins were dragged on a sledge to gallows at Tyburn were they were publicly hanged.

The bodies remained on the gallows until sunset when they were removed and beheaded (Cromwell’s beheading apparently took eight blows). The bodies were believed to have been subsequently thrown into a common grave at Tyburn (although there’s all sorts of speculation surrounding the fate of Cromwell’s – indeed some believe his body had already been removed from Westminster Abbey before the exhumation took place and that it was the body of someone else which was hanged and beheaded).

The decapitated heads, however, were kept. They were placed on 20 foot long spikes at Westminster Hall for public display (Samuel Pepys was among those who saw them).

In 1685, however, the spike holding Cromwell’s head broke in a storm. Cromwell’s head is said to have ended up in the possession of a soldier who took it and hid it in his chimney (a reward was offered but searches were unsuccessful). The fate of the head then remains somewhat clouded but in 1710 it was being displayed in the London museum of Swiss-French collector Claudius Du Puy.

It subsequently passed through various hands until it was eventually bought by Dr Josiah Henry Wilkinson in the early 19th century. It remained in the possession of his family until, following tests which concluded it was indeed Cromwell’s head, it was offered to Sydney Sussex College, Cromwell alma mater, where, in 1960, it was buried in a secret location.