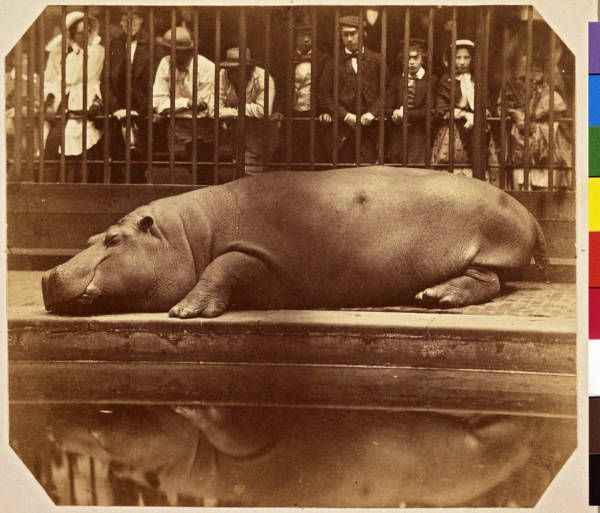

Given our current series on London’s animal life, we thought it an opportune time to take a look at another of London’s most famous animals – in this case a hippopotamus called Obaysch.

Obaysch had been living near (and named for) an island in the River Nile in Egypt. He was gifted by the Ottoman Viceroy, Abbas Pasha, to the British Consul General, Sir Charles Murray (who became known as “Hippopotamus Murray” due to his affection for the animal).

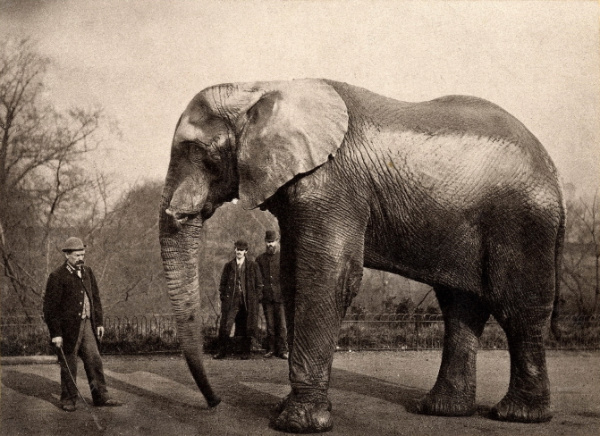

Transported via a steamer to Southampton, he arrived at London Zoo in Regent’s Park on 25th May, 1850.

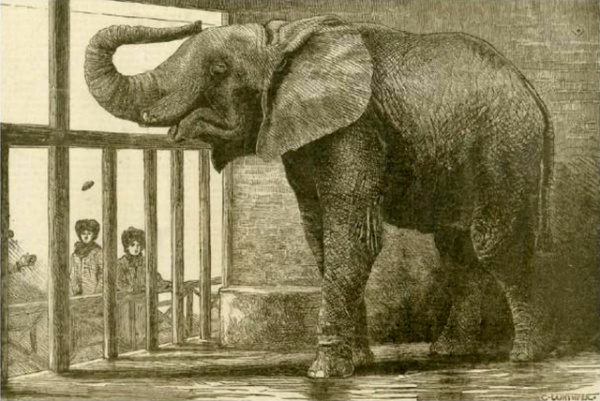

Said to have been the first hippo to be brought to Europe since the days of the Roman Empire, Obaysch soon gained the status of a celebrity at London Zoo with Queen Victoria among the thousands who came to see him (she apparently compared his swimming technique to that of a porpoise) in a craze that became known as “hippomania”.

In 1854, Obaysch was joined by a female hippo Adhela, also known as ‘Dil’, (again as a gift of the Viceroy) who was the first living female hippo in Europe since, you guessed it, Roman times.

In 1860, Obaysch escaped from the hippo enclosure and was only lured back to his enclosure by using one of the zookeepers whom he apparently particularly disliked as bait.

The zoo hoped the pair of hippos would breed but it wasn’t until 1871 that they first became the parents of a baby who sadly, didn’t survive.

Two more babies followed and the second of these, born in November, 1872, and named Guy Fawkes despite subsequently being found to be a female, became the first captive bred hippo to be reared by its mother.

Obaysch died on 11th March, 1878 and Adhela four years later on 16th December, 1882. Guy Fawkes died in March, 1908.