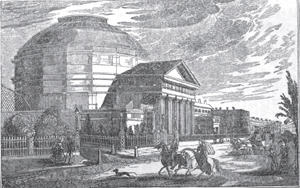

This former fixture of Leicester Square featured a giant globe containing in its innards a detailed physical relief map of the earth’s surface.

The globe was the brainchild of James Wyld (the Younger), a Charing Cross cartographer and map publisher as well as an MP and Geographer to Queen Victoria, who originally planned on exhibiting it at the Great Exhibition of 1851.

The globe was the brainchild of James Wyld (the Younger), a Charing Cross cartographer and map publisher as well as an MP and Geographer to Queen Victoria, who originally planned on exhibiting it at the Great Exhibition of 1851.

At more than 60 feet high, its proposed dimensions, however, meant it would be too big to be housed inside the Crystal Palace being erected in Hyde Park (besides which, Wyld did want to use the globe to promote his map business, something which was frowned upon by the exhibition’s organisers).

So he turned to Leicester Square and, after a rather complicated series of negotiations with the owners of the gardens, was granted permission locate the globe there for 10 years. An exhibition hall large enough to house the globe – and the globe itself – was hastily constructed in time for the Great Exhibition (and the increased visitor numbers it would draw). It opened on 2nd June, 1851, one month after the Great Exhibition.

Inside the gas-lit interior of the globe – entered through four loggias – were a series of galleries and stairways which people could climb to explore the concave surface of the earth depicted – complete with plaster-of-Paris mountain ranges and other topographical details, all created to scale – on the inner side of the great orb.

Initially a great success (visitor numbers are believed to have topped a million in its first year), its appeal faded after a few years amid increasing competition from other attractions such as Panopticon of Science and Art (more of that in an upcoming post) and Wyld was obliged to introduce other entertainments to keep the public satisfied. Wyld himself was among those who gave public lectures at the site.

When the lease expired in 1862, the exhibition hall and the globe were both demolished and the globe sold off for scrap. Wyld, meanwhile, apparently didn’t keep his promise to return the gardens to a satisfactory state but after much wrangling over their fate, they were eventually donated to the City of London.

PICTURE: The Great Globe in cross-section from the Illustrated London News, 7th June, 1851 (via Wikipedia).