In an article first published on The Conversation, LACEY WALLACE of the University of Lincoln, looks at the recent discovery….

Archaeologists from the Museum of London have discovered a well-preserved part of the ancient city of London’s first Roman basilica underneath the basement of an office block. The basilica was constructed for use as a public building in the 70s or early 80s AD.

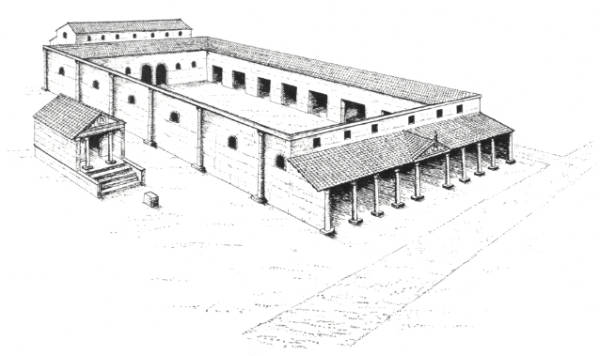

In a Roman town, a basilica was a multi-functional civic building. Often paid for by leading local inhabitants, it provided a large indoor space for public gatherings. These ranged from political speeches to judicial proceedings.

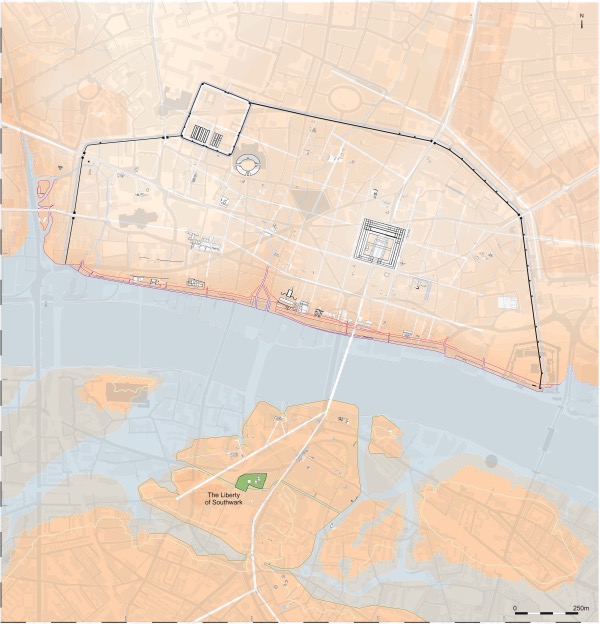

Along with the connected forum – an arrangement of buildings that surrounded an open courtyard space – the building formed the centre of administrative and civic life in the ancient Roman city of Londinium.

Other walls of London’s basilica and forum have been known by archaeologists since the early 1880s. But they were only recognised as remains of the social and civic centre of Londinium in 1923.

The story until now

Peter Marsden, the author of The Roman Forum Site in London (1987), compiled disconnected evidence for the different phases of London’s forum basilica complex.

Referring to the current area of excavations (on Gracechurch Street), he noted that: “More than half of the archaeological deposits still remain, and should be carefully excavated when the opportunity arises, since only then will the history of the site be elucidated.”

Occasional opportunities have arisen to reveal small parts of the forum basilica. For example, during construction of a shaft to install a lift at 85 Gracechurch Street, some important remains from the first century were found. But the excavated area was too small to contribute greatly to our knowledge.

In contrast, the recent work is part of a major redevelopment. It has opened targeted excavation areas where walls of the basilica were expected to be found, exposing substantial parts of the building.

Archaeologists have found one-metre-wide foundations and walls of the interior, some of which probably extend for more than 10 metres in length. The walls are constructed of flint, tile and Kentish ragstone (a type of limestone quarried in Kent), and some stand at four metres high.

What was the basilica for?

Londinium was constructed on an unoccupied site beginning in about AD47 or 48. It began to gain the trappings of a Roman-style town, including a basilica building, in the lead-up to its destruction in the Boudican Revolt in AD60 or 61.

The city did not have a monumental forum and basilica complex until later, however, when a major programme of public and private construction was undertaken in the Flavian period (AD69–96).

London’s Flavian basilica took the plan of a long rectangle (44m x 22.7m) divided into three aisles. There is good evidence from the deeper central aisle (nave) wall foundations that the nave roof was raised to two storeys, to allow for windows to provide internal light.

Shallow foundations crossing the nave are evidence of a raised dais or platform at the eastern end. The speaker or judge would sit there, elevated above the crowds, increasing both his visibility and status. This platform, or “tribunal”, is the area that has recently been revealed.

The basilica would have risen above the north side of the buildings that formed the forum courtyard. It would have dominated the high ground of this monumental space at the highly visible crossroads leading straight up from the Roman Thames bridge.

It would have been the largest building in the area and firmly announced that the people of Londinium were constructing a high-status Roman city.

Rebuilding following the British Queen Boudica’s revolt had been swift. The post-Revolt fort that was built only 100 metres or so down the street had likely been decommissioned and the people were ready to embark on a new phase and a major expansion of the urban centre.

The designs of late first century forum basilica complexes varied across the provinces. But generally they combined religious, civic, judicial and mercantile space.

In places like Pompeii, the forum had developed over time. But, when the town was buried by the ash of Vesuvius in AD79 (approximately the same time the forum basilica of London was built), the focus of the elongated monumental space was the Temple of Jupiter, symbol of the Roman state.

Although a classical temple was constructed to the west of the exterior of Londinium’s Flavian forum, it was clearly separate. No forum in Britannia was dominated by a temple, setting the core of urban space in this province apart from most examples in the rest of the empire.

The Flavian forum basilica at Londinium is one of the earliest examples to demonstrate this characteristic, along with that at Verulamium (St Albans). There, an inscription links the circa AD79–81 construction to the governor Agricola, who is well known among historians from the celebratory biography written by his son-in-law, Tacitus.

The Flavian basilica and forum only stood for about 20 or 30 years, however. With increased prosperity in the early second century, they were demolished and replaced by a new structure which was five times larger, leaving the remains of the first basilica underneath the surface of the later courtyard space.

Museum of London Archaeology will now analyse and publish the results of its find, applying modern methods to advance our understanding of the development of the first forum basilica. We can expect refined dating evidence and an improved understanding of the architecture from the post-excavation analyses. An exhibition space to make the remains visible for the public is also planned.

![]()

Lacey Wallace is a senior lecturer in Roman history & material culture at the University of Lincoln. This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

4. Number four is another in our current series on London battlefields – this time looking at the site where Queen Boudicca is believed to have been defeated by the Romans –

4. Number four is another in our current series on London battlefields – this time looking at the site where Queen Boudicca is believed to have been defeated by the Romans –  A detailed picture of the inhabitants of Roman London, known as Londinium, has been created for the first time, the Museum of London announced this week. Detailed analysis of the DNA of four skeletons has revealed a culturally diverse population. The examined skeletons include that of a Roman woman (pictured left), likely to have been born in Britain with northern European ancestry, found buried with high status grave goods at Harper Road, Southwark, in 1979, and another of a man, whose DNA revealed connections to Eastern Europe and the Near East, who was found at London Wall in 1989 with injuries to his skull which suggest he may have been killed in the nearby amphitheatre before his head was dumped in a pit. The other two skeletons examined were found to be that of a blue-eyed teenaged girl found at Lant Street, Southwark, in 2003, believed to have been born in north Africa, whose ancestors lived in south-eastern Europe and west Eurasia, and that of an older man found at Mansell Street who was born in London and whose ancestry had links to Europe and north Africa. The examination – the first multi-disciplinary study of the inhabitants of a Roman city anywhere in the empire – also revealed that all four suffered from gum disease. Caroline McDonald, senior curator at the museum, said that while it has always been understood Roman London was a culturally diverse place, science was now “giving us certainty”. “People born in Londinium lived alongside people from across the Roman Empire exchanging ideas and cultures, much like the London we know today.” The four skeletons will form the basis of a new free display, Written in Bone, opening at the Museum of London on Friday. PICTURE: © Museum of London

A detailed picture of the inhabitants of Roman London, known as Londinium, has been created for the first time, the Museum of London announced this week. Detailed analysis of the DNA of four skeletons has revealed a culturally diverse population. The examined skeletons include that of a Roman woman (pictured left), likely to have been born in Britain with northern European ancestry, found buried with high status grave goods at Harper Road, Southwark, in 1979, and another of a man, whose DNA revealed connections to Eastern Europe and the Near East, who was found at London Wall in 1989 with injuries to his skull which suggest he may have been killed in the nearby amphitheatre before his head was dumped in a pit. The other two skeletons examined were found to be that of a blue-eyed teenaged girl found at Lant Street, Southwark, in 2003, believed to have been born in north Africa, whose ancestors lived in south-eastern Europe and west Eurasia, and that of an older man found at Mansell Street who was born in London and whose ancestry had links to Europe and north Africa. The examination – the first multi-disciplinary study of the inhabitants of a Roman city anywhere in the empire – also revealed that all four suffered from gum disease. Caroline McDonald, senior curator at the museum, said that while it has always been understood Roman London was a culturally diverse place, science was now “giving us certainty”. “People born in Londinium lived alongside people from across the Roman Empire exchanging ideas and cultures, much like the London we know today.” The four skeletons will form the basis of a new free display, Written in Bone, opening at the Museum of London on Friday. PICTURE: © Museum of London