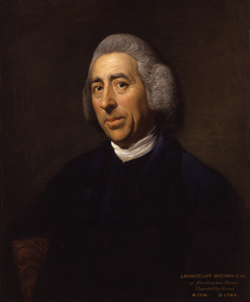

This year marks 300 years since the birth of Lancelot “Capability” Brown, the most famed landscape designer of the Georgian age and a man who has been described as the “father of landscape architecture”.

Brown is understood to have been born in 1716 in the village of Kirkharle in Northumberland, the fifth of six children of a land agent and a chambermaid (he was baptised in on 30th August so it is believed his birth happened sometime earlier that same year).

Brown is understood to have been born in 1716 in the village of Kirkharle in Northumberland, the fifth of six children of a land agent and a chambermaid (he was baptised in on 30th August so it is believed his birth happened sometime earlier that same year).

He attended the village school before he worked as apprentice or assistant to the head gardener in Sir William Loraine’s kitchen garden at Kirkharle Hall.

Having left home in 1741 he joined the gardening staff of Lord Cobham, as one of the gardeners at his property in Stowe, Buckinghamshire.

There he worked with William Kent, another famed landscape architect of the Georgian age and one of the founders of the new English style of gardens, until, at the age of 26, he was appointed head gardener.

He remained in Stowe until 1750 and while there, in 1744, married Bridget Wayet (with whom he went on to have nine children). During his time there, he also created the Grecian Valley and also took on freelance work from Lord Cobham’s noble friends, a fact which allowed him to produce a body of work that would start to make his reputation.

Having struck out on his own from Stowe, he settled with his family in Hammersmith, London, in the early 1750s, already widely known and considered by some the finest gardener in the kingdom.

The work continued to flow in and it’s believed that, over the span of his career, Brown was responsible for designing or contributing to the design of as many as 250 gardens at locations across the UK, – many of which can still be seen today. As well as Stowe, these included gardens at Blenheim Palace, Appuldurcombe House on the Isle of Wight, Warwick Castle, Harewood House and Petworth House in West Sussex.

Following on from the work of Kent, Brown was known for his naturalistic undulating landscapes, in particular their immense scale, flowing waterways and a feature known as a ‘ha-ha’, a ditch which blended seamlessly into the landscape but which was aimed at keeping animals away from the main house of the estate.

His style, which contrasted sharply with the more formalised, geometric gardens epitomised in the French style of gardening, did not, however, meet with universal praise. Criticisms levelled against him including that he had often erased the works of gardeners of previous generations to complete gardens which were, in the end, described by some as looking no different to “common fields”.

It’s worth noting that Brown also dabbled in architecture itself – his first country house project was the remodelling of Croome Court in Worcestershire and he went on to design and contribute to the design of several houses including Burghley House Northamptonshire as well as outbuildings including stable blocks.

The nickname ‘Capability’ apparently came from his habit of informing his client that their estates had great “capability” for improvement. It’s wasn’t apparently a name he used himself.

So established became his reputation that in 1764 Brown was appointed King George III’s Master Gardener at Hampton Court Palace (as well as Richmond and St James’ Palaces), taking up residence with his family at Wilderness House. He also worked on the gardens at Kew Palace.

Brown died on 6th February, 1783, in Hertford Street in London at the door of his daughter Bridget’s house (she had married architect Henry Holland with whom he Brown had, at times, collaborated). He was buried in the churchyard of St Peter and St Paul, the parish church of a small estate Brown owned at Fenstanton Manor in Cambridgeshire.

Brown impact on garden design in England is now undisputed although it wasn’t always the case – his contribution was largely dismissed in the 18th century and it was only in the later 20th century that he had become firmly established as a giant figure in the gardening world.

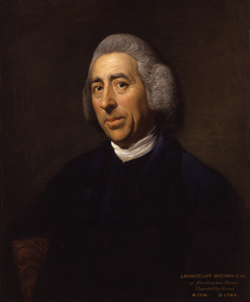

A celebrated portrait of Brown (pictured above) – painted by Nathaniel Dance in about 1773 – is in the collection of National Portrait Gallery.

For more on events surrounding the 300th anniversary of Brown’s birth, see www.capabilitybrown.org.

PICTURE: Capability Brown by Nathaniel Dance, circa 1773. © National Portrait Gallery, London

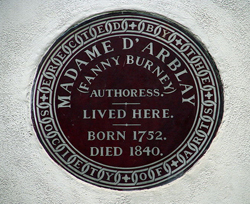

Among them are ballet dancer Margot Fonteyn, suffragette Sylvia Pankhurst, socialite Nancy Astor, and, in recent times, cookery writer Elizabeth David.

Among them are ballet dancer Margot Fonteyn, suffragette Sylvia Pankhurst, socialite Nancy Astor, and, in recent times, cookery writer Elizabeth David.