With the announcement of the second national lockdown and the temporary closure of institutions across the city, we’re again shifting our focus back to online events for the next few weeks. In the meantime, we hope you enjoy our new look (we’ll be doing a bit of experimenting over the next week or two) – and here’s the next couple of entries in the special “most popular posts” countdown we’re running to mark our 10th birthday this year…

Specials

10 London buildings that were relocated…7. St Luke’s, Euston Road…

St Luke’s briefly stood on Euston Road before, thanks to the growing demands of the railways, it was demolished and subsequently rebuilt, brick-by-brick in Wanstead.

Designed by John Johnson (one of the architects of St Paul’s Church, Camden Square), this church was erected on the corner of Euston and Midland Roads between 1856 and 1861. It replaced a temporary iron church which had been erected on the site in the early 1850s.

But the construction in the mid-1860s of St Pancras railway station by the Midland Railway – and the compulsory acquisition of the land – meant the church had to be removed.

While the congregation, compensated with some £12,500 by the railway company, relocated to Kentish Town, the church building itself was sold to another congregation for £500.

Demolished, it was subsequently transported to Wanstead where it was it was rebuilt in 1866-67, with some alterations by Johnson who oversaw the process.

Now the Wanstead United Reformed Church (it changed denominations), it was designated a Grade II-listed building in 2009, partly due to it being one of few examples of a church which has been moved and substantially reconstructed to its original form by the original architect.

10 London buildings that were relocated…6. The spire of St Antholin…

Of medieval origins,the Church of St Antholin, which stood on the corner of Sise Lane and Budge Row, had been a fixture in the City of London for hundreds of years before it was destroyed in the Great Fire of 1666.

Rebuilt to the designs of Sir Christopher Wren, it survived until 1874 when it was finally demolished to make way for Queen Victoria Street.

But, while the building itself was destroyed (and we’ll take a more in-depth look at its history in an upcoming article), a section of Wren’s church does still survive – the upper part of his octagonal spire (apparently the only one he had built of stone).

This was replaced at some stage in the 19th century – it has been suggested this took place in 1829 after the spire was damaged by lightning although other dates prior to the church’s demolition have also been named as possibilities.

Whenever its removal took place, the spire was subsequently sold to one of the churchwardens, an innovative printing works proprietor named Robert Harrild, for just £5. He had it re-erected on his property, Round Hill House, in Sydenham.

Now Grade II-listed, the spire, features a distinctive weathervane (variously described as a wolf’s head or a dragon’s head). Mounted on a brick plinth, it still stands at the location, now part of a more modern housing estate, just off Round Hill in Sydenham.

Exploring London’s 100 most popular posts of all time! – Numbers 48 and 47…

The next two in our countdown…

48. A Moment in London’s History – The execution of George, Duke of Clarence…

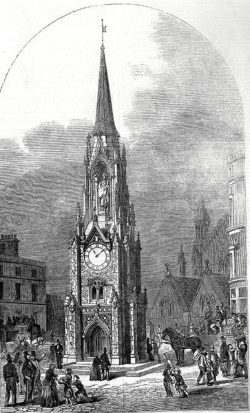

10 London buildings that were relocated…5. The Wellington Clock Tower…

Now situated on the seafront of the town of Swanage in Dorset, the Wellington Clock Tower was originally located at the southern end of London Bridge.

The tower was erected in 1854 as a memorial to the Duke of Wellington, Arthur Wellesley, who had died two years earlier.

Its construction was funded through public subscription and contributions of railway companies with the support of the Commissioners for Lighting the West Division of Southwark. It was designed in the Perpendicular Gothic style by Arthur Ashpitel and, after the foundation stone was laid on 17th June, 1854, took six months to build.

The three level structure, which was topped with a tall spire, housed a clock with four faces. The clock was made by Bennett of Blackheath for the 1851 Great Exhibition but the constant rumbling of the carts passing its new location apparently meant the mechanism never kept good time.

There was also small telegraph office in the ground floor room of the tower. A statue of Wellington was intended to be placed within the open top level but funds apparently ran out before it could be commissioned and it never appeared (Wellington’s declining popularity at the time may have also been a factor).

The location of this rather splendid structure meant, however, that it was soon overshadowed by construction of nearby raised railway lines. When the Metropolitan Police condemned the tower as an obstruction to traffic, it was the final straw and having spent little more than a decade in position, the decision was made to demolish the tower.

It was taken down in 1867 but rather than simply being scrapped, Swanage-based contractor George Burt had the building shipped in pieces – they apparently served as ballast during the journey – to his hometown in Dorset where he presented it as a gift to fellow contractor Thomas Docwra. Docwra had the tower reconstructed in a seafront location on the grounds of his property, The Grove, at Peveril Point.

The rebuilt tower lacked the original clock – its faces were replaced with round windows – and in 1904 the spire was also removed and replaced with a small cupola (there’s been various reasons suggested for this, including that the spire was damaged in a storm or because it was felt to be sacrilegious by the religious family which then owned the property).

The tower, which was granted a Grade II heritage listing in 1952, can still be seen on the Swanage waterfront today.

10 London buildings that were relocated…4. The tower of All Hallows Lombard Street…

One of the lost churches of the City of London, All Hallows Lombard Street once stood on the corner of this famous City street and Ball Alley.

Dating from medieval times, the church was badly damaged in the Great Fire of London and, while the parishioners initially tried their own repairs, it was subsequently rebuilt by the office of Sir Christopher Wren and completed by 1679.

The result was apparently a rather plan building but it did feature a three storey tower (in fact, so hemmed in by other buildings did it become that some called it the “invisible church”). The church also featured a porch which had come from the dissolved Priory of St John in Clerkenwell and had, from what we can gather, been part of the previous building.

Among those who preached in the rebuilt church was John Wesley in 1789 (he apparently forgot his notes and, after some heckling from the congregation, it’s said he never used notes again).

The parish of St Dionis Backchurch was merged with All Hallows when the latter was demolished in 1878 (All Hallows has already been merged with St Benet Gracechurch when that church was demolished in 1868 and St Leonard Eastcheap in 1876). Bells from St Dionis Backchurch were brought to All Hallows following the merger.

The declining residential population in the City saw the consolidation of churches and following World War I, All Hallows Lombard Street was listed for demolition. There was considerable opposition to the decision but structural defects were found in the building’s fabric and demolition eventually took place in 1937.

But there was to be a second life of sorts for the church. The square, stone tower, including the porch and fittings from the church such as the pulpit, pews, organ and stunning carved altarpiece, were all used in the construction of a new church, All Hallows Twickenham in Chertsey Road.

Designed by architect Robert Atkinson, it was one of a couple of new churches built with proceeds from the sale of the land on which All Hallows Lombard Street had stood.

Replacing an earlier chapel, the new Twickenham church was consecrated on 9th November, 1940 by the Bishop of London, Geoffrey Fisher (apparently with the sound of anti-aircraft fire in the background).

The 32 metre high tower houses a peal of 10 bells, including some of those from St Dionis Backchurch, as well as an oak framed gate decorated with memento mori carvings – including skulls and crossbones – which came from All Hallows Lombard Street.

Exploring London’s 100 most popular posts of all time! – Numbers 50 and 49…

The next two entries in Exploring London’s 100 most popular posts countdown…

50. Curious London Memorials – 5. Eros (or the Shaftesbury Memorial Fountain)

10 London buildings that were relocated…3. St Mary Aldermanbury…

This church – not to be confused with the similarly named but still existing St Mary Aldermary – once stood at the corner of Love Lane and Aldermanbury in the City of London.

Founded in the 11th or early 12th century, the church – the name of which apparently relates to an endowment it received from an Alderman Bury, was destroyed in the Great Fire of London in 1666 and rebuilt by Sir Christopher Wren in a simple form with no spire.

It was gutted during the Blitz – one of 13 Wren churches hit on the night of 13th December, 1940 – and the ruins were not rebuilt. Instead, in the 1960s (and this is where we get to the relocation part) a plan was put into action to relocate the church so it could form part of a memorial to Winston Churchill in the grounds of Westminster College in Fulton, Missouri.

It was only after four years of planning and fundraising (the project apparently cost some $US1.5 million with the money raised from donors including actor Richard Burton) that the relocation process finally began in 1965.

(licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

It started with workers in London cleaning, removing and labelling each of the church’s 7,000 stones so they could be reconstructed correctly on the other side of the Atlantic.

They were shipped free-of-charge – the US Shipping Board moved them as ship’s ballast – and then taken by rail to Fulton.

By the time the stones reached Fulton they had been jumbled. And so began the painstaking process of reassembling what was described as the “biggest jigsaw puzzle in the history of architecture” (with the stones spread over an acre, it apparently took a day just to find the first two stones).

While the first shovel on the project had been turned by former US President Harry S Truman on 19th April, 1964 (his connection to the project will become clear), the foundation stone was laid in October, 1966, 300 years after the Great Fire of London.

The shell of the church was completed by May, 1967. Two more years of work saw the church’s interior recreated with English woodcarvers, working from pre-war photographs, to make the pulpit, baptismal font, and balcony (new glass was also manufactured and five new bronze bells cast for the tower). The finished church, which was rededicated in May, 1969, was almost an exact replica of the original but apparently for a new organ gallery and a tower window.

Why Fulton for a tribute to Churchill? The connection between Churchill and Westminster College went back to the post war period – it was in the college’s historic gymnasium building that, thanks to a connection the institution had with President Truman, Churchill was to give one of his most famous speeches – the 1946 speech known as ‘Sinews of Peace’ in which he first put forward the concept of an “Iron Curtain” descending between Eastern and Western Europe.

The church is now one part of the National Churchill Museum, which also includes a museum building and the ‘Breakthrough’ sculpture made from eight sections of the Berlin Wall. It was selected for the memorial – planned to mark the 20th anniversary of Churchill’s speech – thanks to its destruction in the Blitz, commemorating in particular the inspiring role Churchill had played in ensuring the British people remained stalwart despite the air raids.

Meanwhile, back in London the site of the church has been turned into a garden. It contains a memorial to John Heminges and Henry Condell, two Shakespearean actors who published the first folio of the Bard’s works and were buried in the former church. The footings upon which the church once stood can still be seen in the garden and have been Grade II-listed since 1972.

10 London buildings that were relocated…2. Crosby Hall, Chelsea…

This hall was originally constructed in Bishopsgate as the great hall at the heart Crosby Place, the mansion of wealthy merchant and courtier Sir John Crosby.

Built over the decade from 1466 to 1475 on land which had previously been part of St Helen’s Convent, the property became famous for royal connections.

Richard, Duke of Gloucester, had apparently acquired the property from Sir John’s widow by 1483 and it was one of his homes when the Princes in the Tower – Edward V and his younger brother Richard – were murdered, leading to his coronation as King Richard III (as a result the hall is the setting for several scenes in Shakespeare’s Richard III).

Catherine of Aragon, meanwhile, resided in the hall with her retinue after she arrived from Spain on her way to marry Prince Arthur, King Henry VII’s eldest son and then heir (and King Henry VIII’s older brother).

Catherine of Aragon, meanwhile, resided in the hall with her retinue after she arrived from Spain on her way to marry Prince Arthur, King Henry VII’s eldest son and then heir (and King Henry VIII’s older brother).

The property was later – in the 1530s – owned by Sir Thomas More (although he probably never lived here), and subsequently, from about 1576 to 1610 by Sir John Spencer, a Lord Mayor of London (Queen Elizabeth I was apparently among his guests) while Sir Walter Raleigh had lodgings here in 1601.

It served as head office of the East India Company from 1621 to 1638 and, having survived the Great Fire of London, was used in various capacities including as a Presbyterian Meeting House and for various commercial uses, including as a warehouse and restaurant.

In 1908, it was bought by the Chartered Bank of India, Australia and China who wanted to build new offices on the site. The hall was saved from demolition and in 1910 moved stone-by-stone and, under the eye of Walter Godfrey, reconstructed on its present location in Cheyne Walk in Chelsea, a Thames-side site which had formerly been part of Sir Thomas More’s Chelsea garden which was provided by the London County Council.

Having been used to house Belgian refugees during World War I, it was formerly opened by Elizabeth, Duchess of York (later the Queen Mother), in 1926.

Around that time, the property was leased by the British Federation of University Women which had WH Godfrey build a tall Arts and Crafts residential block at right angles to the great hall (the residential block has subsequently bene adapted to appear Jacobean to fit with the hall).

The now Grade II*-listed hall – which, although not complete, is the only surviving example of a City of London medieval merchant’s house – was purchased by philanthropist and businessman Sir Christopher Moran in 1988 and is now part of an expansive private residence designed with the hall as its centrepiece (recent visitors have included Prime Minister Boris Johnson).

PICTURES: Top – sarflondondunc (licensed under CC BY-ND-NC 2.0/Image cropped); Right- Matt Brown (CC BY 2.0/Image cropped)

Exploring London’s 100 most popular posts of all time! – Numbers 52 and 51…

The next two entries in Exploring London’s 100 most popular posts countdown…

10 London buildings that were relocated…1. Marble Arch…

It’s well known that John Rennie’s London Bridge was purchased from the City of London by American entrepreneur Robert P McCulloch and in 1967 relocated to Lake Havasu City in Arizona. But what other London buildings have been relocated from their original site, either to elsewhere in the city or further afield?

First up is Marble Arch, originally built as a grand entrance to Buckingham Palace. Designed by John Nash, the arch was constructed from 1827 and completed in 1833 (there was a break in construction as Nash was replaced by Edward Blore) on the east side of Buckingham Palace for a cost of some £10,000.

Inspired by the Arch of Constantine in Rome (and, it has to be said, some envy over the Arc de Triomphe du Carrousel in Paris, built to commemorate Napoleon’s military victories), the 45 foot high structure is clad in white Carrara marble and decorated with sculptural reliefs by Sir Richard Westmacott and Edward Hodges Baily.

An equestrian statue of King George IV was designed for the top by Francis Leggatt Chantrey but it was never put there (instead, it ended up in Trafalgar Square). The bronze gates which bear the lion of England, cypher of King George IV and image of St George and the Dragon – were designed by Samuel Parker.

The arch, said to be on the initiative of Nash’s former pupil, Decimus Burton, was dismantled and rebuilt, apparently by Thomas Cubitt, in its present location on the north-east corner of Hyde Park, close to Speaker’s Corner, in 1851.

There’s a popular story that the arch was relocated after it was found to be too narrow for the wide new coaches – this seems highly unlikely as the Gold State Coach passed under it during Queen Elizabeth II’s coronation in 1952. Actually, it was moved to create room for Buckingham Palace’s new east facade (meaning the palace’s famous balcony, where the Royal Family gather to wave, now stands where the arch once did).

Whatever the reasons, it replaced Cumberland Gate as the new ornamental entrance to Hyde Park, complementing the arch Decimus Burton had designed for Hyde Park Corner in the park’s south-east.

Subsequent roadworks left the arch in its current position on a traffic island. It stands close to where the notorious gallows known as the “Tyburn Tree” once stood.

The rebuilt, now Grade I-listed, arch contains three small rooms which, until the middle of the 20th century, housed what has been described as “one of the smallest police stations in the world”. Only senior members of the Royal family and the King’s Troop Royal Horse Artillery are permitted to pass through the central gates.

PICTURES: Top – Marble Arch in its current location and; Middle – and an 1837 engraving showing the arch outside Buckingham Palace.

Exploring London’s 100 most popular posts of all time! – Numbers 54 and 53…

The next two entries in Exploring London’s 100 most popular posts countdown…

54. 10 (more) fictional character addresses in London – 6. 9 Bywater Street, Chelsea…

Exploring London’s 100 most popular posts of all time! – Numbers 56 and 55…

The next two entries in Exploring London’s 100 most popular posts countdown…

56. Treasures of London – The Great Vine at Hampton Court Palace

55. 10 sites from Mary Shelley’s London…A recap…

Our new special Wednesday series will launch next week!

Exploring London’s 100 most popular posts of all time! – Numbers 58 and 57…

The next two entries in Exploring London’s 100 most popular posts countdown…

58. Celebrating the Diamond Jubilee with 10 royal London locations – 5. Buckingham Palace…

57. Treasures of London – Peter Pan statue, Kensington Gardens

Exploring London’s 100 most popular posts of all time! – Numbers 60 and 59…

The next two entries in Exploring London’s 100 most popular posts countdown…

60. 10 (more) curious London memorials…3. William Wallace Memorial…

10 disease-related memorials in London – A recap…

We’ve reached the end of our series on disease-related memorials in London. But, before we jump into the next Wednesday series, here’s a recap…

2. Commemorating the monks who died in the Black Death…

3. The Lambeth cholera epidemic memorial…

8. Former site of the Hospital for Tropical Diseases…

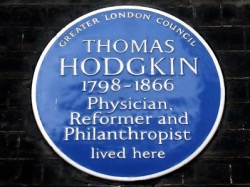

10 disease-related memorials in London…10. Thomas Hodgkin…

Thomas Hodgkin was a physician, pathologist and reformer whose name is now associated with Hodgkin lymphoma, a malignant disease of lymph tissue.

Born in Pentonville in what is now central London, Hodgkin (1798-1866), who trained at St Thomas’s and Guy’s Medical School and the University of Edinburgh, went on to work at Guy’s – where he built up a reputation as a pathologist – and later heading teaching staff at St Thomas’s (after it had split from Guy’s).

Born in Pentonville in what is now central London, Hodgkin (1798-1866), who trained at St Thomas’s and Guy’s Medical School and the University of Edinburgh, went on to work at Guy’s – where he built up a reputation as a pathologist – and later heading teaching staff at St Thomas’s (after it had split from Guy’s).

He first described the disease that bears his name in a paper in 1832 but it wasn’t until 33 years later, thanks to the rediscovery of the disease by Samuel Wilks, that it was named for him.

A Quaker, Hodgkin was also involved in the movement to abolish slavery and also raised concerns about the impact of the West on Indigenous culture. He died while on a trip to Palestine in 1866 and is buried in Jaffa.

Hodgkin is commemorated with an English Heritage Blue Plaque on his former home at 35 Bedford Square in Bloomsbury. Interestingly the house also bears a plaque to another giant of the medical field – Thomas Wakley, the founder of The Lancet.

The plaque commemorating Hodgkin was erected by the Greater London Council in 1985.

Exploring London’s 100 most popular posts of all time! – Numbers 62 and 61…

The next two entries in Exploring London’s 100 most popular posts countdown…

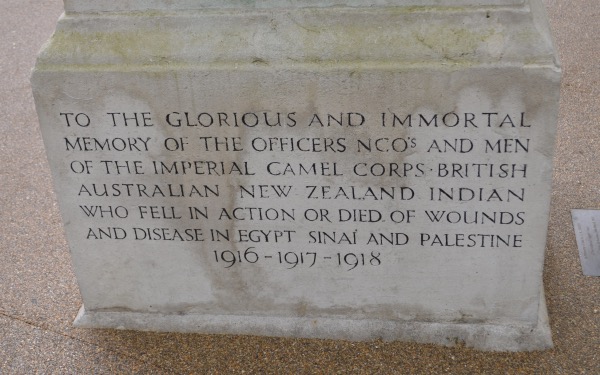

10 disease-related memorials in London…9. The Imperial Camel Corps Memorial…

It’s common to associate war memorials with the commemoration of those who died in combat. But disease, too, is a major killer of soldiers in a time of war yet few memorials explicitly mention disease as cause of death.

It’s common to associate war memorials with the commemoration of those who died in combat. But disease, too, is a major killer of soldiers in a time of war yet few memorials explicitly mention disease as cause of death.

One which does do so, however, is the Imperial Camel Corps Memorial in Victoria Embankment Gardens.

The memorial, which features a bronze figure riding a camel atop a stone plinth has a number of inscriptions and plaques recording the corps’ engagements during World War I and the names of the fallen.

The memorial, which features a bronze figure riding a camel atop a stone plinth has a number of inscriptions and plaques recording the corps’ engagements during World War I and the names of the fallen.

Among them is an inscription which reads “To the glorious and immortal memory of the officers, NCO‘s and men of the Imperial Camel Corps – British, Australian, New Zealand, Indian, who fell in action or died of wounds and disease in Egypt, Sinai and Palestine, 1916 -1917-1918.”

Disease was a significant killer in World War I – it’s estimated that some 113,000 British and Dominion soldiers died of disease – but the number was far fewer than those who died in combat or from wounds, a figure which equates to at least 585,000 (not including the tens of thousands of missing).

Yet, medical advances meant disease was far less a killer than in previous wars – it’s said that in the American Civil War, for example, as many as two-thirds of those who died were the result of various diseases.

The Imperial Camel Corps, which grew to four battalions including two Australian, one British and one New Zealander before it was disbanded after the end of the in 1919, suffered some 246 casualties during World War I – we don’t have a breakdown for how many of those deaths were attributable to disease.

The Grade II-listed memorial, which was sculpted by Major Cecil Brown – himself a veteran of the Corps, was unveiled in July, 1921, in the presence of both the Australian and New Zealand Prime Ministers.

PICTURES: Top and right – David Adams/Below – Matt Brown (licensed under CC BY 2.0)

Exploring London’s 100 most popular posts of all time! – Numbers 64 and 63…

The next two entries in Exploring London’s 100 most popular posts countdown…