We published part I of this two-part article last week. Part II follows…

Marshal had made his name as a knight and, was still in the retinue of Henry, the Young King, heir of Kind Henry II, when he again rebelled against his father (and brother, the future King Richard I).

This was despite a brief rift with the Young King following an accusation that Marshal had slept with Henry’s wife Marguerite (the truth of which remains something of a mystery). Despite their falling out, William and Henry had repaired their relationship to at some degree when, still in rebellion against his father, on 7th June, 1183, the Young King died of dysentery at just the age of 28.

In a dying wish, Henry had asked William to fulfil his vow to go on crusade to the Holy Land. This Marshal duly did, undertaking a pilgrimage to Jerusalem and spending two years in the Middle East before returning to England at around the end of 1185.

In a dying wish, Henry had asked William to fulfil his vow to go on crusade to the Holy Land. This Marshal duly did, undertaking a pilgrimage to Jerusalem and spending two years in the Middle East before returning to England at around the end of 1185.

On his return, he entered the household of King Henry II and was on campaign with him in France in 1189 when the King died at the age of 56.

Marshal’s allegiance was now with his son and heir, King Richard I, the “Lionheart”. He subsequently confirmed his father’s permission for Marshal to marry his ward, the wealthy heiress the 16-year-old Isabel of Clare which Marshal, now 42, quickly did, returning to London to claim his bride who was then living at the Tower of London. It’s believed they may have married on the steps of St Paul’s.

Somewhat controversially, when Richard I set off on the Third Crusade, Marshal remained behind in England, appointed as co-justiciar to govern in the king’s absence. Thanks to his marriage, Marshal was now a major landholder with his base at Striguil Castle (now Chepstow) in the Welsh Marches and he assembled a household befitting of his status. In 1190 his wife Isabel gave birth to a son, ‘Young’ William.

Marshal managed to successfully navigate the dangerous politics of the time as, in the absence of King Richard, his younger brother John manoeuvred to gain power and, following news that Richard had been captured on the way home from the Holy Land and was now imprisoned in Austria, went so far as to open ally himself with the French King Philip Augustus.

Richard was finally released for the exorbitant ransom of 150,000 silver marks and when he arrived back in England, Marshal returned to his side, joining the King as he dealt with the fallout, both in England and France, from John’s treachery (John, meanwhile, was back in his brother’s camp, having begged his forgiveness).

His kingdom largely restored, Richard died in April 1199 after being struck with a crossbow bolt while campaigning in Limousin. Following his death, Marshal supported John’s claim to the throne over his ill-fated nephew Arthur and at John’s coronation he was rewarded by being named, thanks again to his marriage, the Earl of Pembroke – the title of earl being the highest among the English aristocracy.

Pembroke in southern Wales now became his base but following John’s coronation Marshal spent considerable time fighting for the King on the Continent in an ultimately unsuccessful campaign that ended with the English largely driven from France. When Marshal then tried to keep his lands in Normandy by swearing an oath to King Philip, not surprisingly he fell from John’s favour.

Marshal then turned his attention to his own lands in Wales and in Ireland which he visited several times to assert his claim by marriage to the lordship of Leinster. But he again crossed John when he visited in early 1207 without the King’s permission and when John summoned Marshal back to England to answer for his impudence, his lands in Leinster were attacked by the King’s men. John’s efforts to seize Marshal’s Irish domains, however, failed and the King was eventually forced to back down, leaving Marshal to strengthen his position in Ireland.

John and Marshal’s relationship deteriorated even further in 1210 after Marshal was summoned to Dublin to answer for his role in supporting William Briouze, a one-time favourite of the King who had dramatically fallen out him (and who eventually died in exile in 1211 while his wife and eldest son were starved to death in Windsor Castle on John’s orders).

Despite the fact Briouze’s had apparently been on his lands in Ireland for 20 days after they’d fled England to escape the wrathful King, Marshal managed to come out relatively unscathed by the affair – but he was forced to relinquish a castle and place some of his most trusted knights and eldest sons in the King’s custody.

By 1212, however, Marshal was back in royal favour – his sons were freed the following year – and in 1213 he led his forces in support of King John who was facing revolt in England and a possible invasion from France (Marshal subsequently remained in England to guard against attack from the Welsh while the King was in France).

In 1215, Marshal was involved in the creation of the Magna Carta – his name was the first the English lords to appear on the document – and some have even suggested he was one of its principal architects (although this may be overstating his role).

He remained loyal to John in the subsequent strife but he was in Gloucester when King John died in 1216.

Marshal subsequently supported the claim of King John’s son, King Henry III, to the throne and, named as a ‘guardian of the realm’ (a role which was essentially that of a regent), he played an instrumental part in taking back the kingdom for Henry, including successfully leading the royalist forces against a French and rebel force on 20th May, 1217, at Lincoln – a battle which brought about a quick resolution to the ongoing war.

Marshal spent the next couple of years working to restore the King’s rule but in early 1219, at the age of 72, fell ill and retreated to his manor house at Caversham.

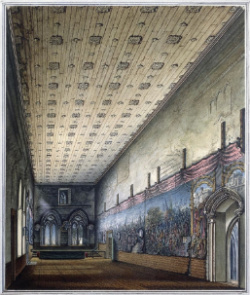

He died around noon on 14th May. His body was taken to London via Reading and after a vigil and Mass at Westminster Abbey, he was interred in the Temple Church.

Marshal’s place of burial was due to an agreement he had made with the Templars back in the 1180s in which he agreed to enter their order before his death in exchange for the gift of a manor. The master of the Templars in England, Aimery of St Maur, had apparently travelled to Caversham before his death to perform the rite.

Marshal’s wife Isabel died the following year and sadly, while he had five sons, the Marshals gradually faded from history, the lack of male heirs in the family eventually leading to the break-up of the family lands.

A towering figure of his age – seen by many as the epitome of what a knight should be, Marshal’s story – despite a minor mention as Pembroke in Shakespeare’s King John – has largely been forgotten. But his influence on the world in which he lived – and hence the shaping of our world today – was significant.

With thanks to Thomas Asbridge’s The Greatest Knight: The Remarkable Life of William Marshal, the Power Behind Five English Thrones…

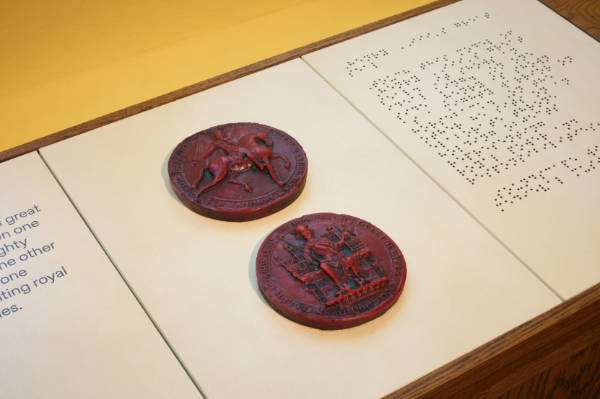

PICTURES: Top – An effigy believed to be that of William Marshal in the Temple Church, London (Michael Wal – licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0). Lower – The Temple Church in London in which William Marshall was buried. PICTURE: David Adams

The first was in Holborn, located between the northern end of Chancery Lane and Staple Inn, and was known as the ‘Old Temple’ after which, in the latter years of the 12th century, the Templars moved their headquarters to the new site – ‘New Temple’ or

The first was in Holborn, located between the northern end of Chancery Lane and Staple Inn, and was known as the ‘Old Temple’ after which, in the latter years of the 12th century, the Templars moved their headquarters to the new site – ‘New Temple’ or