A stroll through the green oasis of the aptly named Green Park in central London. For a look at the history of Green Park, see our earlier post here.

A stroll through the green oasis of the aptly named Green Park in central London. For a look at the history of Green Park, see our earlier post here.

A stroll through the green oasis of the aptly named Green Park in central London. For a look at the history of Green Park, see our earlier post here.

A stroll through the green oasis of the aptly named Green Park in central London. For a look at the history of Green Park, see our earlier post here.

Famous for its associations with London’s theatreland, Drury Lane takes its name from the Drury family who once owned a mansion here.

Previously known as the Via de Aldwych (apparently for a stone monument the Aldwych Cross which stood at the street’s northern end), Drury Lane – which runs between High Holborn and Aldwych – was renamed after Drury House which was built at the southern end of the street.

Previously known as the Via de Aldwych (apparently for a stone monument the Aldwych Cross which stood at the street’s northern end), Drury Lane – which runs between High Holborn and Aldwych – was renamed after Drury House which was built at the southern end of the street.

Some accounts suggest it was Sir Robert Drury (1456-1535), an MP and lawyer, who built the property around 1500; others say it was his son, Sir William Drury, also an MP and a Privy Councillor, who did so in around 1600 – which may mean there were two versions of the one property.

The street, meanwhile, is said to have been briefly renamed Prince’s Street during the reign of King James I (1603-1625) but, following the Restoration in 1660, the name Drury once more gained supremacy.

The origins of the street’s famous theatre (London’s oldest), the Theatre Royal Drury Lane, dates from the same year (see our earlier post here). Other theatres in the street included the Cockpit Theatre which had been designed at one stage by Inigo Jones.

The street is also famous for being the site of the worst outbreak of the plague in London – the Great Plague of 1665, burned away the following year by the Great Fire – and by the 18th century was a slum noted for its seediness, in particular for prostitution (it features in William Hogarth’s work The Harlot’s Progress).

This didn’t change until the second half of the 19th century – author Charles Dickens had been among others who had commented on the poverty he had seen there – when gentrification took hold. Among the shops opened there during this time was the first Sainsbury’s, founded at number 173 in 1869.

Alongside the Theatre Royal Drury Lane (although the main entrance is in Catherine Street), other theatres in the street today include the New London Theatre and the London Theatre.

Both Westminster Abbey and the Palace of Westminster (these days better known as the Houses of Parliament – pictured) pre-date 1215 but unlike today in 1215 the upon which they stood was known as Thorney Island.

Both Westminster Abbey and the Palace of Westminster (these days better known as the Houses of Parliament – pictured) pre-date 1215 but unlike today in 1215 the upon which they stood was known as Thorney Island.

Formed by two branches of the Tyburn River as they ran down to the River Thames, Thorney Island (a small, marshy island apparently named for the thorny plants which once grew there) filled the space between them and the Thames (and remained so until the Tyburn’s branches were covered over).

One branch entered the Thames in what is now Whitehall, just to the north of where Westminster Bridge; another apparently to the south of the abbey, along the route of what is now Great College Street. (Yet another branch apparently entered the river near Vauxhall Bridge).

The abbey’s origins go back to Saxon times when what was initially a small church – apparently named after St Peter – was built on the site. By 960AD it had become a Benedictine monastery and, lying west of what was then the Saxon city in Lundenwic, it become known as the “west minster” (St Paul’s, in the city, was known as “east minster”) and a royal church.

The origins of the Palace of Westminster don’t go back quite as far but it was the Dane King Canute, who ruled from 1016 to 1035, who was the first king to build a palace here. It apparently burnt down but was subsequently rebuilt by King Edward the Confessor as part of a grand new palace-abbey complex.

For it was King Edward, of course, who also built the first grand version of Westminster Abbey, a project he started soon after his accession in 1042. It was consecrated in 1065, a year before his death and he was buried there the following year (his bones still lie inside the shrine which was created during the reign of King Henry III when he was undertaking a major rebuild of the minster).

Old Palace Yard dates from Edward’s rebuild – it connected his palace with his new abbey – while New Palace Yard, which lies at the north end of Westminster Hall, was named ‘new’ when it was constructed with the hall by King William II (William Rufus) in the late 11th century.

Westminster gained an important boost in becoming the pre-eminent seat of government in the kingdom when King Henry II established a secondary treasury here (the main treasury had traditionally been in Winchester, the old capital in Saxon times) and established the law courts in Westminster Hall.

King John, meanwhile, followed his father in helping to establish London as the centre of government and moved the Exchequer here. He also followed the tradition, by then well-established, by being crowned in Westminster Abbey in 1199 and it was also in the abbey that he married his second wife, Isabella, daughter of Count of Angouleme, the following year.

• Three days of events kick off in London tomorrow to mark the 70th anniversary of Victory in Europe (VE) Day. Events will include a Service of Remembrance at the Cenotaph in Whitehall at 3pm tomorrow (Friday) coinciding with two minutes national silence while Trafalgar Square – scene of VE Day celebrations in 1945 – will host a photographic exhibition of images taken on the day 70 years ago (the same images will be on show at City Hall from tomorrow until 5th June) and, at 9.32pm, a beacon will be lit at the Tower of London as part of a nation wide beacon-lighting event. On Saturday at 11am, bells will ring out across the city to mark the celebration and at night, a star-studded 1940s-themed concert will be held on Horse Guards Parade (broadcast on BBC One). Meanwhile, on Sunday, following a service in Westminster Abbey, a parade of current and veteran military personnel will head around Parliament Square and down Whitehall, past the balcony of HM Treasury where former PM Sir Winston Churchill made his historic appearance before crowds on the day, to Horse Guards. A flypast of current and historic RAF aircraft will coincide with the parade and from 1pm the Band of the Grenadier Guards will be playing music from the 1940s in Trafalgar Square. Meanwhile, starting tomorrow, special V-shaped lights will be used to illuminate Trafalgar Square, St Paul’s Cathedral and the Houses of Parliament as a tribute. For more information, see www.gov.uk/government/topical-events/ve-day-70th-anniversary.

• The works of leading London-based photographer Rut Blees Luxemburg are on show in at new exhibition at the Museum of London in the City. London Dust will feature three major newly acquired works by Luxemburg including Aplomb – St Paul’s, 2013, Walkie-Talkie Melted My Golden Calf, 2013, and the film London/Winterreise, 2013. Blees Luxemburg’s images – others of which are also featured in the exhibition – contrast idealised architectural computer-generated visions of London that clad hoardings at City-building sites with the gritty, unpolished reality surrounding these. In particular they focus on a proposed 64 floor skyscraper, The Pinnacle, which rose only seven stories before lack of funding brought the work to a halt. The free exhibition runs until 10th January next year. For more, see www.museumoflondon.org.uk.

• The Talk: The Cutting Edge – Weapons at the Battle of Waterloo. Paul Wilcox, director of the Arms and Armour Research Institute at the University of Huddersfield, will talk about about the weapons used at Waterloo with a chance to get ‘hands-on’ with some period weapons as part of a series of events at Aspley House, the former home of the Iron Duke at Hyde Park Corner, to mark the bicentenary of the Battle of Waterloo. To be held on Monday, 11th May, from 2.30pm to 4pm. Admission charge applies and booking is essential – see www.english-heritage.org.uk/apsley for more.

• On Now: On Belonging: Photographs of Indians of African Descent. A selection of ground-breaking photographs depicting the Sidi community – an African minority living in India – is on show at the National Portrait Gallery off Trafalgar Square. The works, taken between 2005 and 2011, are those of acclaimed contemporary Indian photographer Ketaki Sheth and the exhibition is his first solo display in the UK. They provide an insight into the lives of the Sidi, and include images of a young woman named Munira awaiting her arranged wedding, young boys playing street games, and the exorcism of spirits from a woman as a young girl watches. Admission is free. Runs in Room 33 until 31st August. For more, see www.npg.org.uk.

Send all items for inclusion to exploringlondon@gmail.com.

One of the most famous streets (and photographed) in London (though sadly not open to the public), Downing Street in Whitehall is these days most well-known for being the location, at Number 10, of the official residence of the British Prime Minister.

But Downing Street’s history dates back to a time before the first British PM moved in (this was Sir Robert Walpole in the 1735 and even after that, it didn’t become a regular thing for Prime Ministers to live here until the Twentieth century). And its name bears testimony to its creator, Sir George Downing, a soldier and diplomat described as “a miserly and at times brutal” man who served first under both Oliver Cromwell and, following the Restoration, King Charles II (and was, coincidentally, one of the first graduates of Harvard University).

In the 1650s, Sir George took over the Crown’s interest in land here, just east of St James’s Park, and intended to build a row of townhouses upon it. His ambitions were delayed, however, due to an existing lease with the descendants of Elizabethan courtier Sir Thomas Knyvet who had once lived in a large home on the site of what is now Number 10 Downing Street.

By the 1680s, however, the lease had expired and between 1682-84, Downing was able to construct a cul-de-sac, closed at the St James’s Park end, featuring either 15 or 20 two storey terraced townhouses with stables and coach-houses, designed by no less than Sir Christopher Wren.

While the homes were apparently of shoddy craftsmanship and stood upon poor foundations (Churchill famously wrote that Number 10 was “shaky and lightly built by the profiteering contractor whose name they bear”), the street apparently attracted some notable residents from the start.

These included the Countess of Yarmouth, who briefly lived at Number 10 in the late 1680s, Lord Lansdowne and the Earl of Grantham, and even, briefly, apparently the diarist James Boswell in the mid 1700s. Downing himself isn’t thought to have ever lived here – he retired to Cambridge a few months after the houses were completed.

The houses between Number 10 and Whitehall – on the north side of the street – were taken over by the government and eventually demolished in the 1820s to allow for the construction of offices for the Privy Council, Board of Trade and Treasury while the houses on the south side remained until they were demolished in the early 1860s to make way for the Foreign, India, Colonial and Home Offices.

The numbers in the street have changed since Downing’s houses were first built. Of the original homes in the street only Number 10 (home of the PM) and Number 11 (home of the Chancellor of the Exchequer) survive.

Access to the street has been restricted since the 1980s with the current black steel gates put in place in 1989.

An underground tunnel apparently runs under the street connecting number 10 with Buckingham Palace and the underground bunker, Q-Whitehall, built in the 1950s in the event of nuclear war.

Tomorrow is the 25th April – commemorated every year as Anzac Day in Australia in memory of that country’s soldiers who lost their lives. This year marks 100 years since Australian troops first landed at Gallipoli during World War I.

While attention will be focused on Anzac Cove in modern Turkey and the Australian war memorials on what was the Western Front in western Europe, in London there will be several events including a wreath laying ceremony at The Cenotaph in Whitehall, a commemoration and thanksgiving service in Westminster Abbey and a dawn service held at the Australian War Memorial in Hyde Park Corner.

This last memorial, dedicated to the more than 100,000 Australians who died in both world wars, was unveiled on Armistice Day, 2003, in the presence of Queen Elizabeth II, then-Australian PM John Howard and then British PM Tony Blair.

It records the 23,844 names of town where Australians who served in World War I and II were born.

Superimposed over the top are 47 of the major battles they fought. Principal architect Peter Tonkin said the somewhat curvaceous design of the memorial, made of grey-green granite slabs, “reflects the sweep of Australian landscape, the breadth and generosity of our people, the openness that we believe should characterise our culture”.

For more on the wall – including the ability to search for town names – see www.awmlondon.gov.au.

There are numerous memorials to Sir Winston Churchill around London and today we’ll look at a handful of them (while next week we’ll take a look at a couple of the most unusual memorials). We’ve already looked at the most famous statue of him in Parliament Square (in an earlier post here), but here’s some more…

• Allies, Mayfair. These almost life-size bronze statues, located at the juncture of Old and New Bond Streets, depict Churchill and US President Franklin D Roosevelt in an informal pose, sitting and talking together on a bench. The sculpture was a gift from the Bond Street Association to the City of Westminster and was unveiled by Princess Margaret on 2nd May, 1995 commemorating 50 years since the end of World War II. It is the work of US sculptor Lawrence Holofcener. There’s a space between the two World War II leaders where the passerby can sit and have their picture taken between them.

• Allies, Mayfair. These almost life-size bronze statues, located at the juncture of Old and New Bond Streets, depict Churchill and US President Franklin D Roosevelt in an informal pose, sitting and talking together on a bench. The sculpture was a gift from the Bond Street Association to the City of Westminster and was unveiled by Princess Margaret on 2nd May, 1995 commemorating 50 years since the end of World War II. It is the work of US sculptor Lawrence Holofcener. There’s a space between the two World War II leaders where the passerby can sit and have their picture taken between them.

• Member’s Lobby, House of Commons. We’ve already mentioned this bronze statue (see our previous post here), erected in 1969, which stands just outside Churchill Arch opposite one of another former PM, David Lloyd George. It is the work of Croatian-born sculptor Oscar Nemon who also created numerous other busts of the former PM now located both in the UK (one of which is mentioned below) and around the world.

• Great Hall, Guildhall. Commissioned by the Corporation of the City of London and unveiled in 1955, this bronze statue shows Churchill, wearing a suit and bow tie, seated in an armchair and looking ahead. Another work of Nemon’s, it was commissioned as a tribute to “the greatest statesman of his age and the nation’s leader in the Great War of 1939-1945”.

• Outside former Conservative Club, Wanstead. A very thick-necked bust of Churchill, erected in 1968, sits outside the 18th century mansion in Wanstead High Street, north-east London, which was once the Conservative Club and is now occupied by a restaurant. The bigger than life-sized bust is the work of Italian artist Luigi Fironi and stands on a plinth once part of old Waterloo Bridge. Churchill was the Conservative member for this area between 1924-1964 and based at the club from 1930 to 1940.

Wishing all of our readers a very happy Easter!

• It’s party time at Hampton Court Palace this weekend as the palace celebrates its 500th anniversary with festivities including a spectacular (and historic) light show. Friday, Saturday and Sunday nights the palace will be open for an evening of festivities including the chance to taste-test pork cooked in the Tudor kitchens, enjoy a drink at a pop-up bar in the Cartoon Gallery, listen to live performances of period music in the state apartments and watch a 25 minute sound and light show in the Privy Garden taking viewers on a journey through the palace’s much storied past culminating in a fireworks finale. The nights run from 6.30pm to 9.15pm. Admission charge applies. For more, see www.hrp.org.uk/HamptonCourtPalace/. PICTURE: HRP/Newsteam

• A luxury wartime bunker, a map room dating from the 1930s and a walk-in wardrobe complete with vintage fashion are among five new rooms at Eltham Palace in south London which are opening to the public for the first time this Easter. The rooms also include a basement billiards room and adjoining bedrooms, one of which features one of the first showers ever installed in a residential house in the UK. They have been restored as part of English Heritage’s major £1.7 million makeover of the property – the childhood home of King Henry VIII which was converted into a stunning Art Deco gem in the 1930s. Visitors will be invited to join one of Stephen and Virginia Courtauld’s legendary cocktail party’s of the 1930s while children can take part in an interactive tour exploring the story of the animals that lived at the palace including Mah-Jongg, the Courtauld’s pet lemur (who had his own heated bedroom!). Admission charge applies. For more, see www.english-heritage.org.uk/eltham. Meanwhile, anyone wishing to donate to support the renovation of the map-room can do so at www.english-heritage.org.uk/donate-eltham.

• A new exhibition showcasing the latest scientific displays concerning the life and death of King Richard III has opened at the Science Museum. King Richard III: Life, Death and DNA, which opened last Wednesday – the day before the king’s remains were reinterred at Leicester Cathedral, features an analysis of Richard III’s genome, a 3D printed skeleton (only one of three in existence) and a prototype coffin. It explores how CT scans were used to prove the king’s fatal injuries at the Battle of Bosworth in 1485 were caused by a sword, dagger and halberd (a reproduction of the latter is on display). The exhibition will run until 25th June. Entry is free. For more, see www.sciencemuseum.org.uk/RichardIII.

• Join Shaun the Sheep and friends for Kew Garden’s annual Easter Egg hunt this Sunday. The hunt will take place from 9.30am to noon (or when the eggs run out!) with participants needing to find three sheep and collect a token/chocolate dropping from each before finding the Easter bunny and claiming eggs supplied by Divine chocolate. Shaun, meanwhile, who hit the big screen for the first time this year, will be found in the Madcap Meadow until 12th April. Admission charge applies. For the full range of events taking place at the gardens this Easter season, check out www.kew.org. PICTURE: RBG Kew.

• Join Shaun the Sheep and friends for Kew Garden’s annual Easter Egg hunt this Sunday. The hunt will take place from 9.30am to noon (or when the eggs run out!) with participants needing to find three sheep and collect a token/chocolate dropping from each before finding the Easter bunny and claiming eggs supplied by Divine chocolate. Shaun, meanwhile, who hit the big screen for the first time this year, will be found in the Madcap Meadow until 12th April. Admission charge applies. For the full range of events taking place at the gardens this Easter season, check out www.kew.org. PICTURE: RBG Kew.

• London’s Boroughs are turning 50 and to celebrate London councils – working with the London Film Archive – have released a short film telling the story of the past half century. Follow this link to see it. Councils across the city, meanwhile, are holding events throughout the year to mark the occasion – check with your local council for details; some, like Barking and Dagenham, and Camden have dedicated pages.

• The first chief of the Secret Intelligence Service, Sir Mansfield Cumming, has been commemorated with an English Heritage blue plaque at his former home in Westminster. Known as ‘C’ thanks to his habit of initialling papers (a tradition which has been carried on by every chief since), Cumming was chief of the Foreign Section of the Secret Service Bureau from 1909 until his death in 1923. Flats 53 and 54 at 2 Whitehall Court – now part of Grade II*-listed The Royal Horseguards Hotel – served as Cumming’s home and office at various times between 1911 and 1922. The plaque was unveiled by current Secret Intelligence Service chief, Alex Younger. Meanwhile, Amelia Edwards, pioneering Egyptologist, writer, and co-founder of the Egypt Exploration Fund, has also been honoured with a blue plaque on her former home in Islington. Edwards lived at 19, Wharton Street in Clerkenwell between 1831 and 1892. For more, see www.english-heritage.org.uk/visit/blue-plaques/.

Send all items for inclusion to exploringlondon@gmail.com.

Nestled next to Westminster Abbey opposite the Houses of Parliament, St Margaret’s has long been known as the “parish church of the House of Commons” (although we should point out it’s not officially a parish church). As a result, it probably doesn’t come as a surprise that it has a couple of significant links to former PM Winston Churchill.

Among the most momentous personal occasions was when Churchill married Clementine Hozier in the church on 12th September, 1908, after a short courtship. A headline in the Daily Mirror called it ‘The Wedding of the Year’.

Among the most momentous personal occasions was when Churchill married Clementine Hozier in the church on 12th September, 1908, after a short courtship. A headline in the Daily Mirror called it ‘The Wedding of the Year’.

After the fighting of World War II ended in 1945, on VE Day Churchill, in a move reflecting that taken by then PM David Lloyd George after World War I, led the members of the House of Commons in procession from the Houses of Parliament into the church for a thanksgiving service.

In 1947, the church was the scene of another Churchill wedding, this time that of Sir Winston’s daughter, Mary who was wedded to Captain Christopher Soames of the Coldstream Guards on 11th February.

WHERE: St Margaret’s Church, Westminster (nearest Tube stations are St James’s Park and Westminster); WHEN: 9.30am to 3.30pm weekdays/9.30am to 1.30pm Saturday/2pm to 4.30pm Sunday; COST: Free; WEBSITE: www.westminster-abbey.org/st-margarets-church.

Throughout his life – as a child, bachelor, husband and family man, Sir Winston lived in many properties in London (although, of course, a couple of the most famous properties associated with him – his birthplace, Blenheim Palace, and the much-loved family home, Chartwell in Kent – are located outside the city). But, those and 10 Downing Street aside, here are just some of the many places he lived in within London…

• 29 St James’s Place, St James: Having been born at Blenheim Palace in Oxfordshire and then having spent time in Dublin, at the age of five (1880) he came to live here with his family. He remained here until 1882 when he was sent off to school in Ascot (he later attended schools in Sussex and, most famously, Harrow School). The family, meanwhile, moved to a townshouse at 2 Connaught Place which backed on to Hyde Park.

• 33 Eccleston Square, Pimlico: The Churchills moved here in 1909 and it was here that their first two children Diana and Randolph were born in 1909 and in 1911. The family remained here until 1913. A blue plaque marks the property.

• Admiralty House, Whitehall: The Churchills first moved into Admiralty House – part of the Admiralty complex on Whitehall – in 1913 (from the aforementioned Eccleston Square) after Churchill was made First Lord of the Admiralty. They remained here until 1915 – years he would go onto to describe as the happiest in his life – before he resigned but returned in 1939 when he was once again appointed to the position.

• 2 Sussex Square, Bayswater: In 1920, the Churchills bought this property just north of Hyde Park which they kept until 1924 when they moved into 11 Downing Street (see below). The property is marked with a blue plaque.

• 11 Downing Street, Whitehall: The Churchills lived at 11 Downing Street when Sir Winston was Chancellor of the Exchequer, from 1925 to 1929. The property, located in Downing Street, is not accessible to the public.

• 11 Morpeth Mansions, Morpeth Terrace, Westminster: The Churchill family lived at this Westminster address between 1930 and 1939 (prior to him becoming Prime Minister). The property is marked by a brown plaque.

• 28 Hyde Park Gate, Kensington: Churchill died in this Grade II-listed, mid 19th century property on the morning of 24th January, 1965. The couple moved in after the end of World War II and, while it’s not clear whether they fully vacated the residence when he was prime minister between 1951-55, it remained their property until his death 10 years later. The property next door, number 27, provided accommodation for his staff. The property is marked with a blue plaque.

Now a museum, the Churchill War Rooms is actually the underground bunker system beneath Whitehall from where Churchill directed operations during the Blitz of World War II.

The subterranean complex includes a series of historic rooms where Churchill and his cabinet met which remain in the same state they were in when the lights were switched off at the end of the war in 1945. There’s also a substantial cutting-edge museum dedicated to exploring Churchill’s life which boasts an interactive “lifeline” containing more than 1,100 images and a similar number of documents as well as animations and films.

The subterranean complex includes a series of historic rooms where Churchill and his cabinet met which remain in the same state they were in when the lights were switched off at the end of the war in 1945. There’s also a substantial cutting-edge museum dedicated to exploring Churchill’s life which boasts an interactive “lifeline” containing more than 1,100 images and a similar number of documents as well as animations and films.

With the coming conflict on the horizon, the complex was constructed from 1938 to 1939 as an emergency government centre in the basement of the now Grade II* listed government building then known as the New Public Offices (and now home to HM Treasury). It became operational on 27th August, 1939, shortly before the outbreak of the war.

Key rooms include the Map Room (pictured, top, it was manned around the clock by military officers producing intelligence reports) and the War Cabinet Room where more than 100 meetings of Cabinet were held (including just one gathering of Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain’s cabinet in October, 1939).

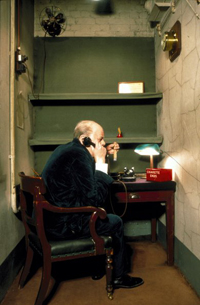

Other facilities included a private office/bedroom for Churchill (this came with BBC broadcasting equipment which Churchill used four times and, although it had a bed, Churchill apparently rarely used it), the Transatlantic Telephone Room (pictured above, it was disguised as a toilet) from where Churchill could speak directly to the US President. There are also staff dormitories, bedrooms for officers and government ministers, and rooms for typists and telephone switchboard operators.

In October, 1940, a massive layer of concrete – up to five feet thick and known simply as ‘The Slab’ – was added to protect the rooms. Other protective devices included a torpedo net slung across the courtyard overhead to catch falling bombs and an air filtration system to prevent poisonous gases entering.

Abandoned after the war, the premises hosted some limited tours but, despite growing demand to see inside, it wasn’t until the early 1980s when PM Margaret Thatcher pushed for the rooms to be opened to the public that the Imperial War Museum eventually took over the site. The museum opened on 4th April, 1984, in a ceremony attended by the PM as well as members of Churchill’s family and former staff.

Then known as the Cabinet War Rooms, they were extended in 2003 to include rooms used by Churchill, his wife and associates, and, in 2005, following the development of the Churchill Museum, it was rebranded the Churchill Museum and Cabinet War Rooms. In 2010, the name was shortened to the Churchill War Rooms. The entrance to the premises was redesigned in 2012.

Among the objects in the museum are one of Churchill’s famous “siren suits”, an Enigma machine and the flag from his funeral.

WHERE: Churchill War Rooms, Clive Steps, King Charles Street (nearest Tube stations are Westminster and St James’s Park); WHEN: 9.30am to 6pm daily; COST: £18 adults (with donation)/£9 children aged 5-15 (with donation)/£14.40 concessions (with donation) (family tickets available); WEBSITE: www.iwm.org.uk/visits/churchill-war-rooms/

PICTURES: Churchill War Rooms/Imperial War Rooms

The origins of the Thames-side district Lambeth’s name are not as obscure as it might at first seem.

The origins of the Thames-side district Lambeth’s name are not as obscure as it might at first seem.

First recorded in the 11th century, the second part of the name – which apparently is related to/a derivative of the word ‘hithe’ or ‘hythe’ – means a riverside landing place while the first part of the name is exactly what it seems – ‘lamb’. Hence, Lambeth was a riverside landing or shipping place for lambs and cattle.

There has apparently been a suggestion in the past that the word ‘lamb’ actually derived from an Old English word meaning muddy place, hence the meaning was ‘muddy landing place’. That theory, however, is now generally discounted.

Lambeth these days is still somewhat in the shadow of the much more famous Westminster river bank opposite but among its attractions is the Imperial War Museum (located in the former Bethlem Hospital, see our earlier post here), Lambeth Palace (pictured above) – London residence of the Archbishop of Canterbury, and, of course, the promenade of Albert Embankment (sitting opposite Victoria Embankment).

The headquarters of MI6 is also located here in a 1994 building designed by Terry Farrell (among its claims to fame is its appearance in the opening scenes of the James Bond film, The World Is Not Enough).

Lambeth – the name is also that of the borough in which the district is located – was formerly home to the Vauxhall Pleasure Gardens which closed in the mid 19th century (see our earlier post here).

Of course, no look at London sites associated with Sir Winston Churchill would be complete without a mention of the Palace of Westminster, better known as the Houses of Parliament.

Churchill made his maiden speech in the House of Commons on 18th February, 1901, having won the seat of Oldham for the Conservative Party the year before (he switched to the Liberal Party in 1904 and eventually rejoined the Conservatives in 1924).

Over his long career in politics (he was an MP for 62 years), he served in a variety of roles including the President of the Board of Trade, Home Secretary, First Lord of the Admiralty, Minister of Munitions, Chancellor of the Exchequer, and twice, Prime Minster.

Some of the most famous speeches Churchill gave in the House of Commons were during World War II – they include the ‘blood, toil, tears and sweat’ speech given on 13th May, 1940 – the first after he had been made Neville Chamberlain’s replacement as PM, the ‘we shall fight them on the beaches’ speech given on 4th June, 1940, and the ‘this was their finest hour’ speech of 18th June, 1940, in which he gave the ‘Battle of Britain’ its name and, as the name suggests, first recorded the phrase “their finest hour” (the speech ended with it).

Churchill’s last speech to Parliament was given on 1st March, 1955, in which he spoke about the British development of a hydrogen bomb.

There’s several places within the Houses of Parliament which now bear Churchill’s name. Among them are the Churchill Room (named as such in 1991 when ownership of the room passed from the Lords to the Commons, it features two of his paintings and a bronze bust of the PM).

They also include the Churchill Arch – this leads from the Members’ Lobby into the Commons Chamber and is flanked by a 1969 statue of Churchill ( and one of fellow former PM, David Lloyd George (one foot on each of the statues has been burnished thanks to the practice of MPs to touch them as they enter the Commons Chamber).

It took on its current name after it was rebuilt following damage from bombs during World War II – at Churchill’s suggestion damaged stone was reused in its construction as a memorial to the “ordeal” Westminster had endured during the war. The statue of Churchill, incidentally, was the focus of recent commemorations on the 50th anniversary of his death.

Churchill’s stamp can also be seen on the Commons Chamber itself – it was he who recommended that when the chamber was rebuilt after World War II that it retain its rectangular shape rather than be redesigned in a semi-circle.

Churchill’s body lay in state in Westminster Hall prior to his funeral service in January, 1965 (for more on that, see our previous post here.

For more on Churchill’s Parliamentary career, check out the UK Parliament’s Living History page here: www.parliament.uk/about/living-heritage/transformingsociety/private-lives/yourcountry/collections/churchillexhibition/.

The world recently paused to mark the 50th anniversary of the death of former British PM, Sir Winston Churchill (see our earlier post here), so we’re launching a new series looking at 10 sites associated with Churchill in London.

The world recently paused to mark the 50th anniversary of the death of former British PM, Sir Winston Churchill (see our earlier post here), so we’re launching a new series looking at 10 sites associated with Churchill in London.

Given the recent anniversary, we’re starting at a site close to the end of his story, at St Paul’s Cathedral, where his state funeral was held on 30th January, 1965.

Code-named ‘Operation Hope Not’, the funeral had been thoroughly planned in the years leading up to the former PM’s death and took place just six days after he passed. Having lain in state in Westminster Hall for three days (during which time it’s estimated 320,000 filed past his flag draped body), his coffin, carried on a gun carriage pulled by 120 members of the Royal Navy, was escorted by more than 2,300 personnel from the military as it made its way through city streets lined with thousands of people to St Paul’s for the service.

During the service, the catafalque containing Churchill’s body stood on a raised platform beneath the central dome surrounded by six candlesticks. Among the official pallbearers – who marched before it down the aisle – were another former PM, Clement Attlee, along with military figures like Field Marshal Lord Slim and Admiral of the Fleet Lord Mountbatten of Burma.

A plethora of world leaders representing 112 nations attended the funeral service including six sovereigns, six presidents and 16 prime ministers. Among them – in an unprecedented move for a state funeral – was Queen Elizabeth II (sovereigns do not normally attend non-family funerals) along with Prince Philip and Prince Charles.

It’s estimated that as some 350 million people around the globe tuned in to watch the funeral on TV.

After the service, Churchill’s body was taken to Tower Pier (near the Tower of London) where, to the sound of a 19-gun salute fired by the Royal Artillery, he was loaded on the MV Havengore. Sixteen RAF Lightning aircraft then did a flypast as he was transported upriver to Festival Pier with dockers dipping their cranes in salute as the boat passed (this journey was recreated last week using the original barge in commemoration of the 50th anniversary of his death).

On its arrival at Festival Pier, the body was then taken to Waterloo Station from where it went via train in a specially prepared carriage (the refurbished funeral train has been brought back together at the National Railway Museum at York) to be buried in St Martin’s churchyard in Bladon, Oxfordshire – a site not far from his birthplace at Blenheim Palace.

A bronze memorial plaque commemorating where Churchill’s catafalque stood in St Paul’s is set before the Quire steps while in 2004, the Winston Churchill Memorial Screen was unveiled in the crypt where it stands in line with the final resting places of both Admiral Lord Nelson and the Duke of Wellington.

For more on the state funeral, St Paul’s has a great page of detail which you can find here, including downloadable copies of the Order of Service and other documents.

This massive Gothic revival structure would have dramatically changed the skyline of Westminster but, perhaps thankfully, never got further than the drawing board.

The proposal was mooted in the early 1900s apparently amid concerns that, thanks to the number of monuments and memorials being placed within its walls, Westminster Abbey was becoming overcrowded. It was also apparently proposed as a memorial to Prince Albert.

The proposal was mooted in the early 1900s apparently amid concerns that, thanks to the number of monuments and memorials being placed within its walls, Westminster Abbey was becoming overcrowded. It was also apparently proposed as a memorial to Prince Albert.

The designs were the work of John Pollard Seddon – architect for the Church of England’s City of London Diocese – and another architect Edward Beckitt Lamb. They consisted of a 167 metre (548 foot) high tower and adjoining vast reception hall and numerous other galleries which sat at a right angle to the eastern end of the abbey minster (pictured).

Given the Clock Tower containing Big Ben is only 97.5 metres (320 feet high), the structure would have completely dominated its surrounds.

The project was exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1904 but, requiring an enormous and impractical budge (not to mention its dominating aesthetics), was never pursued any further.

It was in 1265, 750 years ago this month, that a parliament convened by English rebel leader Simon de Montfort, took place in Westminster Hall (exterior pictured below).

The French-born De Montfort, who led a group of rebel barons, was riding high after defeating King Henry III at the Battle of Lewes on 14th May, 1264. While he ruled in the king’s name through a council – having captured both the king and his son Prince Edward, the monarch was no more than a figurehead. De Montfort was effectively the man in charge.

In a bid to solidify his hold on the country, he summoned not only the barons and clergy but knights representing counties to a parliament along with – for the first time – representatives from major towns and boroughs like York, Lincoln and the Cinque Ports (the representatives were known as burgesses).

It’s this latter move which led this three month-long parliament to be described as the first English parliament and which has led de Montfort to be described by some as the founder of the House of Commons.

Presided over by King Henry III, the parliament was held in Westminster Hall in London – a city loyal to de Montfort’s cause. It dealt with a range of political matters including the enforcement of a series of government reforms known as the Provisions of Westminster which had been aimed at strengthening baronial rights and the role of courts.

Prince Edward (later King Edward I) managed to escape from de Montfort’s clutches later in 1265 and led forces against de Montfort. The rebel leader was killed at the Battle of Evesham on 4th August, 1265.

The UK Parliament is marking the 750th anniversary of De Montfort’s Parliament with a series of events (along with the 800th anniversary of the sealing of the Magna Carta) – check out www.parliament.uk/2015 for more.

• All 100,000 tickets for London’s New Year’s Eve fireworks are now booked, the Greater London Authority announced this week. They’ve advised those without a ticket to avoid the area around Embankment and South Bank on the night, saying that the best alternative view of the fireworks will be live on BBC One. Meanwhile, don’t forget the New Year’s Day Parade which will kick off in Piccadilly (near junction with Berkeley Street) from noon on New Year’s Day. The parade – which takes in Lower Regent Street, Pall Mall, Trafalgar Square and Whitehall before finishing at 3.30pm at Parliament Square in Westminster – will feature thousands of performers. Grandstand tickets are available. For more, see www.londonparade.co.uk.

• The National Gallery has acquired French artist Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot’s work, The Four Times of Day, it was announced this month. The 1858 work, acquired with the aid of the Art Fund, has something of a star-studded pedigree – it was bought by Frederic, Lord Leighton, in 1865, and the four large panels were displayed at his London home until his death. In the same family collection for more than a century after that, they have been on loan to the National Gallery since 1997. They complement 21 other paintings by Corot in the gallery’s collection. The Four Times of Day can be seen in Room 41. Entry is free. For more, see www.nationalgallery.org.uk.

Exploring London is taking a break over Christmas, so this will be the last This Week in London update until mid-January. But we’ll still be posting some of our other usual updates including our most popular posts for 2014 round-up!

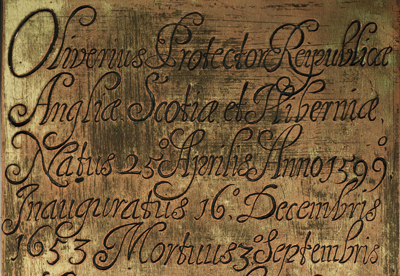

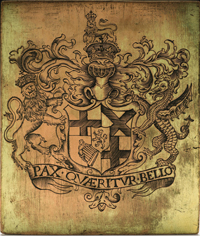

The copper gilt plate found on former Lord Protector Oliver Cromwell’s breast when his body was exhumed will be put up to auction in London later today. Sotheby’s says that according to contemporary reports, the plate was found in a leaden canister lying on Cromwell’s chest when the coffin – interred in

The copper gilt plate found on former Lord Protector Oliver Cromwell’s breast when his body was exhumed will be put up to auction in London later today. Sotheby’s says that according to contemporary reports, the plate was found in a leaden canister lying on Cromwell’s chest when the coffin – interred in  the Henry VII Chapel in Westminster Abbey – was opened by James Norfolke, Serjeant of the House of Commons, on the orders of parliament on 26th January, 1661 – just two years from Cromwell was buried. Norfolke apparently took the plate which was subsequently handed down through his family. It was not the only relic associated with Cromwell to survive – while Cromwell’s body, along with that of regicides Henry Ireton and John Bradshaw, was hanged at Tyburn and then apparently buried in an unmarked grave pit, his head was placed on a spike above Westminster Hall and remained there for more than 20 years until it blew down in a gale and was taken by a guard. It apparently subsequently passed through numerous private hands before, in 1960, it was interred in a secret location in the chapel of Sidney Sussex College in Cambridge. Meanwhile, the plate – which bears the arms of the Protectorate on one side and an inscription in Latin with the dates of Cromwell’s birth, inauguration as Lord Protector and death on the other – is listed with an estimated price of between £8,000 and £12,000. For more on the item, see www.sothebys.com/en/auctions/ecatalogue/2014/english-literature-history-childrens-books-illustrations-l14408/lot.3.html.

the Henry VII Chapel in Westminster Abbey – was opened by James Norfolke, Serjeant of the House of Commons, on the orders of parliament on 26th January, 1661 – just two years from Cromwell was buried. Norfolke apparently took the plate which was subsequently handed down through his family. It was not the only relic associated with Cromwell to survive – while Cromwell’s body, along with that of regicides Henry Ireton and John Bradshaw, was hanged at Tyburn and then apparently buried in an unmarked grave pit, his head was placed on a spike above Westminster Hall and remained there for more than 20 years until it blew down in a gale and was taken by a guard. It apparently subsequently passed through numerous private hands before, in 1960, it was interred in a secret location in the chapel of Sidney Sussex College in Cambridge. Meanwhile, the plate – which bears the arms of the Protectorate on one side and an inscription in Latin with the dates of Cromwell’s birth, inauguration as Lord Protector and death on the other – is listed with an estimated price of between £8,000 and £12,000. For more on the item, see www.sothebys.com/en/auctions/ecatalogue/2014/english-literature-history-childrens-books-illustrations-l14408/lot.3.html.

Prolific early 19th century architect Sir John Soane designed many public buildings in London including, famously, the Bank of England (since considerably altered) and the somewhat revolutionary Dulwich Picture Gallery. He also designed a number that were merely fanciful works and never commissioned nor constructed.

Foremost among them was a sprawling royal palace which would occupy part of Green Park off Constitution Hill.

Foremost among them was a sprawling royal palace which would occupy part of Green Park off Constitution Hill.

While Soane had been designing royal palaces as far back as the late 1770s when in Rome on his Grand Tour, in 1821 he designed one, apparently as a new home for the newly crowned King George IV.

Birds-eye view drawings show a triangular-shaped palace with grand porticoes at each of the three corners as well as in the middle of each of the three sides. Three internal courtyards surround a large central dome.

Despite Soane’s hopes for a royal commission, the king appointed John Nash to the job of official architect and so Soane’s palace never went any further than the drawing board.

He also designed a grand gateway marking the entrance to London at Kensington Gore through which the monarch would travel when heading to the State Opening of Parliament in Westminster – it, too, was never realised.

PICTURE: Wikipedia