In an unusual ‘Famous Londoners’, this week we’re looking at a former inhabitant of London who we still know relatively little about.

In an unusual ‘Famous Londoners’, this week we’re looking at a former inhabitant of London who we still know relatively little about.

The remains of the teenaged girl – believed to have been aged between 13 and 17 years – were found in 1995 when the conically-shaped skyscraper at 30 St Mary Axe, fondly known as the Gherkin (and then formally known as the Swiss Re Tower), was being constructed.

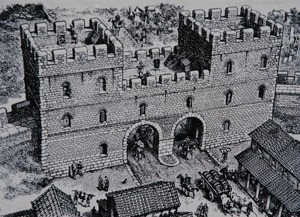

The girl, whose skeleton was unearthed where the foundations now stand, was buried sometime between 350 and 400 AD in what appeared to be an isolated grave which would have lain just outside the edge of early Roman Londinium.

The body lay with the girl’s head to the south and the arms folded across. Pottery was found associated with the body which provided dating information.

After being exhumed, the skeleton was housed at the Museum of London for some 12 years before in 2007 it was reburied near the new building. The burial featured a ceremony at nearby St Botolph-without-Aldgate followed by a procession to the gravesite where a dedication took place which included “music and libations”. Among those who attended was the Lady Mayoress of the City of London.

There’s an inscription in honour of the girl on a stone feature outside the building in both Latin and English while a stone set in the pavement decorated with laurel leaves marks the (re)burial spot.

Other recent Roman remains found in London include the skeleton of a young Roman woman, believed to date from the 4th century, which was found still inside its sarcophagus at a site in Spitalfields and a series of two dozen Roman-era skulls which, likely to date from the first century A, were found during excavations for the Crossrail project in 2013. It has been suggested they may have been Britons executed for their role in the famed Queen Boudicca’s rebellion against the Romans in 61 AD.