LondonLife – Barbican curvature…

Located in the heart of the post-war Brutalist Barbican development is the second largest conservatory in London.

Designed by the complex’s architects Chamberlin, Powell and Bon, the 23,000 square foot steel and glass conservatory – only bested in size by the Princess of Wales Conservatory at Kew Gardens – was planted in the early 1980s and opened in 1984.

It now houses some 1,500 species of plants and trees from areas as diverse as the bushland of South Africa to the Brazilian coast.

Among the species on show are the tree fern and date palm as well as the Swiss cheese plant and coffee and ginger plants.

The conservatory also features pools containing koi, ghost, and grass carp from Japan and America, as well as other cold water fish such as roach, rudd, and tench and terrapins. An Arid House attached to the east of the conservatory features a collection of cacti, succulents and cymbidiums (cool house orchids).

The conservatory is just one of several distinct gardens at the Barbican complex. These include water gardens located in the midst of lake which feature a range of plants growing in the water itself as well as in a series of sunken pods which are reached by sunken walkways.

Since 1990 the estate has also been home to a wildlife garden which, boasting ponds, a meadow and orchard, is home to more than 300 species including the Lesser Stag Beetle and House Sparrow.

WHERE: The Barbican Conservatory, Barbican Centre, Silk Street (nearest Tube stations are Barbican, Farringdon and Liverpool Street; WHEN: Selected days, from 12pm (check website to book tickets); COST: Free; WEBSITE: www.barbican.org.uk/whats-on/2022/event/visit-the-conservatory.

Long connected with the low end trade in words, Grub Street was once located on the site where the Barbican development now stands.

Long connected with the low end trade in words, Grub Street was once located on the site where the Barbican development now stands.

The street – its name possibly comes from a man called Grubbe or refers to a street infested with worms – was located in the parish of St Giles-without-Cripplegate outside the city wall. It northwards ran from Fore Street to Chiswell Street and had numerous alleys and courts leading off it.

Originally located in an area of open fields used for archery and so inhabited by bowyers and others associated with the production of bows and arrows, the relative cheapness of the land – due to its marshiness – later saw the Grub Street and its surrounds become something of a slum, an area of “poverty and vice”.

During the mid-17th century, it became known as a home for (often libellous or seditious) pamphleteers, journalists and publishers seeking to escape the attention of authorities.

And so began the association of Grub Street with writing “hacks”, paid line-by-line as they eked out a living in tawdry garrets (although how many actually worked in garrets remains a matter of debate). The word “hack”, incidentally, is derived from Hackney, and originally referred to a horse for hire but here came to refer to mediocre writers churning out copy for their daily bread rather than any sense of artistic merit.

Residents included Samuel Johnson (early in his career), who, in 1755 included a definition for it in his famous dictionary – “a street near Moorfields in London, much inhabited by writers of small histories, dictionaries and temporary poems, whence any mean production is called grubstreet”, and 16th century historian John Foxe, author of the famous Book of Martyrs.

The street, which was also referenced by the likes of Alexander Pope and Jonathan Swift as a symbol of lowbrow writing, was renamed Milton Street (apparently after a builder, not the poet) in 1830. Part of it still survives today but most of it disappeared when the Barbican complex was created between the 1960s and 1980s.

PICTURE: John Rocque’s map of 1746 showing Grub Street.

A new exhibition featuring designs for the 10 new Elizabeth line Underground stations has opened at the Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA). Platform for Design: Stations, Art and Public Space provides insights into the design of the new railway – part of the massive Crossrail project, its stations and public spaces which are slated to open in 2018. Each of the new stations will have their own distinct character designed to reflect the environment and heritage of the area in which they are located. The new Elizabeth line station at Paddington, for example, is said to “echo the design legacy of Brunel’s existing terminal building” while the design of the new Farringdon station is inspired by the historic local blacksmith and goldsmith trades and the distinctive architecture of the Barbican. Many of the new stations will also featured permanent, integrated works of art design to create a “line-wide exhibition”. The Elizabeth line runs from Heathrow and Reading in the west across London to Abbey Wood and Shenfield. The exhibition at RIBA at 66 Portland Place in Marylebone runs until 14th June. Admission is free. For more on the exhibition, including the accompanying programme of events, see www.crossrail.co.uk/news/news-and-information-about-crossrail-events.

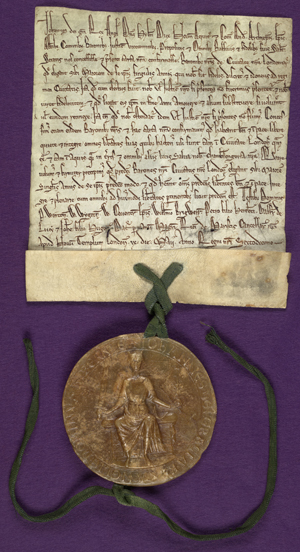

It was on 9th May, 2015, 800 years ago this year that, in the lead-up to the creation of the Magna Carta in June, King John issued a charter granting the City of London the right to freely elect its own mayor.

The charter, which was issued at the Temple – King John’s power base to the west of the City (for more on it, see our earlier post here), was a fairly blatant bid to keep the support of the city.

Known simply as the King John Charter, it stated that the barons of the city, “may choose to themselves every year a mayor, who to us may be faithful, discreet, and fit for government of the city, so as, when he shall be chosen, to be presented unto us, or our justice if we shall not be present”.

Known simply as the King John Charter, it stated that the barons of the city, “may choose to themselves every year a mayor, who to us may be faithful, discreet, and fit for government of the city, so as, when he shall be chosen, to be presented unto us, or our justice if we shall not be present”.

In return, the mayor was required to be presented to the monarch to take an oath of loyalty each year – a practice commemorated in the Lord Mayor’s Show each November.

The charter, which has a particularly good impression of the king’s seal, is currently on display in the City of London’s newly opened Heritage Gallery, located at the Guildhall Art Gallery.

The event was one of a series leading up to the signing of the Magna Carta in June. Only 10 days after King John issued the charter to the City of London, rebel barons, who have previously taken Bedford, marched on the city to demand their rights and arrived their before the Earl of Salisbury (whom John had ordered to occupy the city).

Aldgate was apparently opened to them by some supporters within the city and the forces of the rebel barons went on to attack the home of royalists as well as those of Jews along with a Jewish burial ground in Barbican – the latter because Jewish moneylenders had lent money to the king.

They later besieged the Tower of London and while they couldn’t take the fortress, their seizure of the city was enough to help force the king to open negotiations late in the month, asking the Archbishop of Canterbury, Stephen Langdon, on 27th May to arrange truce (which, while it was apparently not observed terribly well, did help pave the path to the Magna Carta).

The exhibition at the Heritage Gallery runs until 4th June. For more information, see www.cityoflondon.gov.uk/things-to-do/visiting-the-city/attractions-museums-and-galleries/guildhall-art-gallery-and-roman-amphitheatre/Pages/Heritage-Gallery.aspx.

PICTURE: City of London: London Metropolitan Archives

The playwright is believed to have lived in several different locations in London and is also known to have invested in a property. Here we take a look at a couple of different locations associated with him…

• Bishopsgate: Shakespeare is believed to have lived here in the 1590s – in 1596 tax records show he was living in the parish of St Helen’s. The twin-nave church of St Helen’s Bishopsgate (pictured), which would have been his parish church, still stands. In fact, there is a window to Shakespeare’s memory dating from the late 19th century.

• Bishopsgate: Shakespeare is believed to have lived here in the 1590s – in 1596 tax records show he was living in the parish of St Helen’s. The twin-nave church of St Helen’s Bishopsgate (pictured), which would have been his parish church, still stands. In fact, there is a window to Shakespeare’s memory dating from the late 19th century.

• Bankside: In the late 1590s, Shakespeare apparently moved across the Thames to Bankside where he lived at a property on lands in the Liberty of the Clink which belonged to the Bishop of Winchester. The exact address remains unknown.

• Silver Street, Cripplegate: It’s known that in 1604, Shakespeare moved from Bankside back to the City – it’s been speculated outbreaks of plaque may have led him to do so. Back in the City, he rented lodgings at the house of Christopher and Mary Mountjoy in on the corner of Monkwell and Silver Streets in Cripplegate, not far from St Paul’s Cathedral. Mountjoy was a refugee, a French Huguenot, and a tire-maker (manufacturer of ladies’ ornamental headresses). The house, which apparently stood opposite the churchyard of the now removed St Olave Silver Street, was consumed in the Great Fire of London in 1666 (the church was also lost in the Great Fire). The former church site is now located on the south side of London Wall. Silver Street itself was wiped out in the Blitz and is now lost under the Barbican redevelopment but the house lives on in a representation found on a late 16th century map created by Ralph Agas.

• Ireland Yard, Blackfriars: In 1613, Shakespeare purchased the former gatehouse of the Blackfriars Priory located here, close to the where the Blackfriars Theatre was located. It is believed the property was purchased as an investment – there’s no evidence he ever lived there but it was passed to his daughter Susanna after his death. Incidentally, there is some speculation that Shakespeare may have lived in Blackfriars when he first came to London – a man believed to have been a boyhood friend from Stratford, Richard Field, who was known to have lived there.

For a more in-depth look at Shakespeare’s time in Silver Street, see Charles Nicholl’s The Lodger: Shakespeare on Silver Street.

Though it’s these days associated with a Brutalist housing estate and performing arts centre based in the north of the City of London, the name Barbican has been associated with the area on which the estate stands for centuries.

The word barbican (from the Latin barbecana) refers to an outer fortification designed to protect the entrance to a city or castle. In this case it apparently referred to watchtower which may have had its origins in Roman or Saxon times (or maybe both). The City of London website suggests it was located “somewhere between the northern side of the Church of St Giles Cripplegate and the YMCA hostel on Fann Street”.

The word barbican (from the Latin barbecana) refers to an outer fortification designed to protect the entrance to a city or castle. In this case it apparently referred to watchtower which may have had its origins in Roman or Saxon times (or maybe both). The City of London website suggests it was located “somewhere between the northern side of the Church of St Giles Cripplegate and the YMCA hostel on Fann Street”.

When-ever it was built, the watchtower was apparently demolished on the orders of King Henry III in 1267, possibly as a response to Londoners who had supported England’s barons when they had rebelled against him. One source suggests the tower was rebuilt during the reign of King Edward III but, if so, the date of its subsequent demolition remains unknown.

Later residents of the area – which become known as a place to trade new and used clothes – included John Milton and William Shakespeare.

The area known as Barbican was devastated by bombing raids in World War II. Discussions on the future of the site started in 1952 and for more than 10 years plans for redeveloping the area were debated until finally, in the early 1960s, work began on what is now the Barbican Estate including three tall residential towers (part of the residential estate is pictured above). Completed in the mid 1970s, the Brutalist design of the complex, which features buildings named after historical figures associated with the area, means it meets with strong reactions from those who encounter it whether love – or hate.

Construction of the arts centre – known as the Barbican Centre – the largest performing arts centre in Europe and home to the London Symphony Orchestra – was started in the early 1970s. The £156 million centre was eventually opened by Queen Elizabeth II in 1982.

Other buildings within the Grade II listed complex include the Guildhall School of Music and Drama, the City of London School for Girls and a YMCA.

Originally the northern gate of the Roman fort constructed in about 120 AD, Cripplegate was rebuilt several times during the medieval period before finally being demolished in 1760 as part of road widening measures.

The origins of the gate’s name are shrouded by the mists of time but it has been suggested that it was named for the beggars or cripples that once begged there or that it could come from an Anglo-Saxon word crepel which means a covered walkway.

The origins of the gate’s name are shrouded by the mists of time but it has been suggested that it was named for the beggars or cripples that once begged there or that it could come from an Anglo-Saxon word crepel which means a covered walkway.

The name may even be associated with an event which took place there in 1100 when, fearful of marauding Danes, Bishop Alwyn ordered the body of Edmund the Martyr, a sainted former Anglo-Saxon king, to be tranferred from its usual home in Bury St Edmunds to St Gregory’s Church near St Paul’s in London so that it could be kept safe. It was said that when the body passed through the gate, many of the cripples there were miraculously healed.

The gate (pictured here in an 18th century etching as it would have looked in 1663 in an image taken from a London Wall Walk plaque), which gave access in medieval times to what was then the village of Islington, was associated with the Brewer’s Company and was used for some time as a prison.

It was defensive works, known as a barbican, built on the northern side of the gate in the Middle Ages which are apparently responsible for the post World War II adoption of the name Barbican for that area of London which once stood outside the gate’s northern facade (the gates stood at what is now the intersection of Wood Street and St Alphage Garden).

The gate’s name now adorns the street known as Cripplegate as well as the name of the church St Giles Cripplegate, which originally stood outside the city walls. It is also the name of one of the 25 wards of the City of London. The original site of the gate is marked with a blue plaque.