Eighteenth century physician Dr Richard Mead is noted not only for his attendance on the rich and famous of his time – including royalty – but also for his philanthropy, his expansive collections and, importantly, his contributions in the field of medicine.

Born in Stepney, London, on the 11th August, 1673, as the 11th of 13 children of nonconforming minister Matthew Mead, Mead studied both Utrecht and Leiden before receiving his MD in Italy. Returning to England in 1696, he founded his own medical practice in Stepney.

He married Ruth Marsh in 1699 and together the couple had at least eight children, several of whom died young, before her death in 1720 (he subsequently married again, this time to Anne, daughter of a Bedfordshire knight, Sir Rowland Alston).

Having published the then seminal text – A Mechanical Account of Poisons – in 1702, the following year Mead was admitted to the Royal Society. He also took up a post as a physician at St Thomas’ Hospital, a job which saw him move to a property in Crutched Friars in the City – his home until 1711, when he relocated to Austin Friars.

It was after this that he become friends with eminent physician John Radcliffe who chose Mead as his successor and, on his death in 1714, bequeathed him his practice and his Bloomsbury home (not to mention his gold-topped cane, now on display at the Foundling Museum – see note below).

Following Radcliffe’s death, in August of that year Dr Mead attended Queen Anne on her deathbed. Other distinguished patients over his career included King George I, his son Prince George and daughter-in-law Princess Caroline – in fact he was appointed as official physician to the former prince when elevated to the throne as King George II – as well as Sir Isaac Newton, lexicographer Dr Samuel Johnson, Alexander Pope, Sir Robert Walpole and painter Antoine Watteau.

Mead, who had been named a governor of St Thomas’ in 1715 and elected a fellow of the Royal College of Physicians in 1716, was over the years recognised as an expert in a range of medical fields – including, as well as poisons, smallpox, scurvy and even the transmission of the plague.

Among the many more curious stories about Dr Mead is one concerning a ‘duel’ (or fistfight) he apparently fought with rival Dr John Woodward outside Gresham College in 1719 over their differences in tackling smallpox and others which concern experiments he conducted with venomous snakes to further his knowledge of venom before writing his text on poisons.

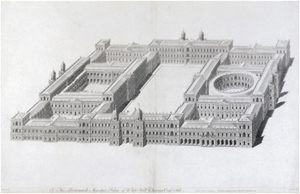

Dr Mead was also known for his philanthropy and became one of the founding governors of the Foundling Hospital (as well as being its medical advisor) – a portrait of him by artist Allan Ramsay (for whom he was a patron), currently hangs at the museum.

Dr Mead, who by this stage lived in Great Ormond Street in Bloomsbury (the property, which backed onto the grounds of the Foundling Museum and which Mead had moved into after his first wife’s death, later formed the basis of the Great Ormond Street Hospital for Children), is also noted for the large collection he gathered of paintings – including works by Dürer, Holbein, Rembrandt, and Canaletto, a library of more than 10,000 books, antiquities and classical sculpture as well as coins and jewels, all of which scholars and artists could access at his home (it took some 56 days to sell it all after his death).

While Dr Mead – who died on 16th February, 1754 – was buried in the Temple Church, there is a monument to him – including a bust by Peter Scheemakers – in the north aisle of Westminster Abbey.

Dr Mead is currently being honoured in an exhibition at the Foundling Museum – The Generous Georgian: Dr Richard Mead – which runs until 4th January. There’s an accompanying blog here which provides more information on his life and legacy.

The house was built in 1683 although who it was built for remains something of a mystery. It was apparently was demolished within 50 years or so when the east side of the street, which had been laid out in the late 1600s, was recorded as the site of a series of “pest” (plague) houses.

The house was built in 1683 although who it was built for remains something of a mystery. It was apparently was demolished within 50 years or so when the east side of the street, which had been laid out in the late 1600s, was recorded as the site of a series of “pest” (plague) houses.