Throughout his life – as a child, bachelor, husband and family man, Sir Winston lived in many properties in London (although, of course, a couple of the most famous properties associated with him – his birthplace, Blenheim Palace, and the much-loved family home, Chartwell in Kent – are located outside the city). But, those and 10 Downing Street aside, here are just some of the many places he lived in within London…

• 29 St James’s Place, St James: Having been born at Blenheim Palace in Oxfordshire and then having spent time in Dublin, at the age of five (1880) he came to live here with his family. He remained here until 1882 when he was sent off to school in Ascot (he later attended schools in Sussex and, most famously, Harrow School). The family, meanwhile, moved to a townshouse at 2 Connaught Place which backed on to Hyde Park.

• 33 Eccleston Square, Pimlico: The Churchills moved here in 1909 and it was here that their first two children Diana and Randolph were born in 1909 and in 1911. The family remained here until 1913. A blue plaque marks the property.

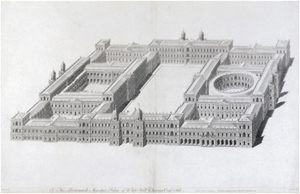

• Admiralty House, Whitehall: The Churchills first moved into Admiralty House – part of the Admiralty complex on Whitehall – in 1913 (from the aforementioned Eccleston Square) after Churchill was made First Lord of the Admiralty. They remained here until 1915 – years he would go onto to describe as the happiest in his life – before he resigned but returned in 1939 when he was once again appointed to the position.

• 2 Sussex Square, Bayswater: In 1920, the Churchills bought this property just north of Hyde Park which they kept until 1924 when they moved into 11 Downing Street (see below). The property is marked with a blue plaque.

• 11 Downing Street, Whitehall: The Churchills lived at 11 Downing Street when Sir Winston was Chancellor of the Exchequer, from 1925 to 1929. The property, located in Downing Street, is not accessible to the public.

• 11 Morpeth Mansions, Morpeth Terrace, Westminster: The Churchill family lived at this Westminster address between 1930 and 1939 (prior to him becoming Prime Minister). The property is marked by a brown plaque.

• 28 Hyde Park Gate, Kensington: Churchill died in this Grade II-listed, mid 19th century property on the morning of 24th January, 1965. The couple moved in after the end of World War II and, while it’s not clear whether they fully vacated the residence when he was prime minister between 1951-55, it remained their property until his death 10 years later. The property next door, number 27, provided accommodation for his staff. The property is marked with a blue plaque.