Simon Murphy is a curator at the London Transport Museum in Covent Garden – the museum is currently celebrating the 150th birthday of the Underground with a series of events including a landmark exhibition on the art of the Tube (Poster Art 150 – London Underground’s Greatest Designs)…

How significant was the construction of the London Underground in world terms? And how does it stack up 150 years later? “The Metropolitan Railway was a true world class pioneer, but like all pioneers it made mistakes that subsequent operators learned from. Similarly the first tube railways tested the ground for others to follow. But these pioneering lines are still part of today’s world class Tube network, and some of the original stations, like King’s Cross, are still amongst the busiest, so they must have been on the right track.”

How significant was the construction of the London Underground in world terms? And how does it stack up 150 years later? “The Metropolitan Railway was a true world class pioneer, but like all pioneers it made mistakes that subsequent operators learned from. Similarly the first tube railways tested the ground for others to follow. But these pioneering lines are still part of today’s world class Tube network, and some of the original stations, like King’s Cross, are still amongst the busiest, so they must have been on the right track.”

I understand the initial stretch of line ran between Farringdon and Paddington. How quickly were other sections opened? “The Metropolitan Railway’s first extension was authorised by Parliament in 1861, two years before the original line even opened. The railway made a profit in its first year, so financial backing was relatively easy to find, and the extension east to Moorgate opened in 1865, with a westward extension to South Kensington following in 1868. The Met’s main competitor, the Metropolitan District Railway, opened its first section from South Ken to Westminster in 1868. The plan was for the two companies to work together to create an Inner Circle service, but their respective directors fell out and the Circle was not completed until 1884.”

How many miles of line is the Underground composed of today? “The first underground started with less than four miles of track and seven stations; today’s system has 250 miles of track, serving 270 stations.”

When were steam trains on the Underground replaced? “Steam trains worked in central London until 1905, but were still used on the furthest reaches of the Met until 1961.”

When did the Underground take on the name ‘Tube’? “The Central London Railway opened with a flat fare of 2d in 1900, and was promoted as the Twopenny Tube – the name caught on, although the Underground has only been referring to itself officially as the Tube since the 1990s.”

It’s fairly widely known that Underground stations and tunnels were used as air raid shelters during World War II. Do you know of any other different uses they have been put to? “The station at South Kentish Town on the Northern Line closed in 1924, but the surface building, still looking very much like a station is now occupied by a branch of Cash Converters. During the war unfinished tunnels on the Central line were occupied by a secret factory run by Plessey Components. Also during the war, paintings from the Tate Gallery were stored in a disused part of Piccadilly Circus station for safe keeping.”

It’s fairly widely known that Underground stations and tunnels were used as air raid shelters during World War II. Do you know of any other different uses they have been put to? “The station at South Kentish Town on the Northern Line closed in 1924, but the surface building, still looking very much like a station is now occupied by a branch of Cash Converters. During the war unfinished tunnels on the Central line were occupied by a secret factory run by Plessey Components. Also during the war, paintings from the Tate Gallery were stored in a disused part of Piccadilly Circus station for safe keeping.”

Stylish design has always been an important part of the Underground’s appeal. What’s your favourite era stylistically when it comes to the Underground and why? “Most people admire the golden age of the 1920s and 30s when the Underground’s corporate identity and personality reached its peak with Charles Holden’s architecture, the roundel, Harry Beck’s diagrammatic map and the amazing posters issued in that era, but personally I find the earlier period from 1908 to 1920 more interesting. You can trace the roots of each element of today’s brand being developed at this time, under Frank Pick’s critical eye, starting with the early solid-disc station name roundels, the joint promotion of the individual tube railways under the UndergrounD brand and the introduction of Edward Johnston’s typeface. You can see the company gaining confidence and momentum, especially in relation to the increasingly sophisticated posters and promotion that Pick commissioned.”

Can you tell us a bit about how the London Transport Museum is marking the 150th anniversary? “We started the year by bringing steam back to the Circle line, after restoring an original Metropolitan Railway carriage and overhauling an original Met steam locomotive, and have just opened our fabulous overview of the 150 best Underground posters at the museum in Covent Garden, which runs until October. We are opening our Depot store, near Acton Town station in April for a steam weekend, and have a range of lectures and evening events at Covent Garden linking to the history of the Underground and its poster art heritage. There’s also our comprehensive new history of the Tube published last year and a wide range of new products and souvenirs in our amazing shop.”

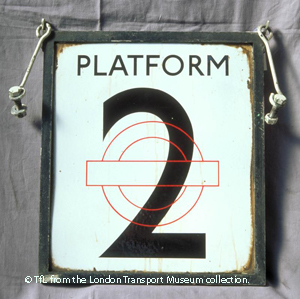

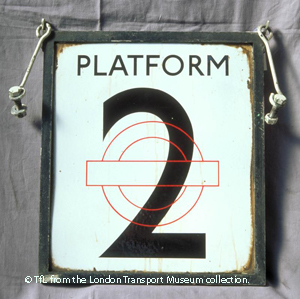

What are some of your favourite Underground-related objects on display at the museum? “The Design for Travel gallery on the ground floor is the literal and metaphorical heart of the Museum for me. Packed with close to 300 objects including signs, posters, models, leaflets and other documents, it’s hard to single out individual items, but I love the simplicity of the small ‘Platform 2’ hanging sign (pictured right) – it’s a real example of the design consistency and attention to detail that I associate with the Underground.”

What are some of your favourite Underground-related objects on display at the museum? “The Design for Travel gallery on the ground floor is the literal and metaphorical heart of the Museum for me. Packed with close to 300 objects including signs, posters, models, leaflets and other documents, it’s hard to single out individual items, but I love the simplicity of the small ‘Platform 2’ hanging sign (pictured right) – it’s a real example of the design consistency and attention to detail that I associate with the Underground.”

And lastly, can you tell us a couple of little-known facts about the Underground? History is more than a chronological list of facts, and what one person finds fascinating sends another to sleep, so it’s quite a challenge to choose something that is little known, but genuinely interesting, but I’ll try: I grew up near Brent Cross station so I might be biased, but I reckon that if there was a top trumps for Underground lines, the Northern line would win. It has the longest escalators (at Euston), the deepest lift shaft (at Hampstead), the highest point ve sea level (on a viaduct near Mill Hill East), the longest tunnels (between East Finchley and Morden – 17 miles) and has had more names than any other line – it only became the Northern line in 1937.”

IMAGES: Top: Steam engine at Aldgate (1902); Middle: Platform 2 sign, 1930s design; and Bottom, Angel Underground Station (1990s). © TfL from the London Transport Museum collection.

Poster Art 150 – London Underground’s Greatest Designs runs at the London Transport Museum until October. Admission charge applies. For more (including the many events around the exhibition), see www.ltmuseum.co.uk/whats-on/events/events-calendar#posterart150.

Located close to Tower Hill in the eastern part of the City, this pub – and indeed the street in which it sits (at number 64-73) – takes its name from a former nunnery that was once located here.

Located close to Tower Hill in the eastern part of the City, this pub – and indeed the street in which it sits (at number 64-73) – takes its name from a former nunnery that was once located here.