Taken along New River Walk which follows the course of the “New River” in Islington. The New River, completed in 1613, was a man-made canal which brought water from Hertfordshire to New River Head in Clerkenwell (it now takes water to reservoirs in Stoke Newington). PICTURE: David Adams.

Waterways

Lost London – Chapel of St Thomas á Becket…

Known informally as the Chapel on the Bridge, the Chapel of St Thomas á Becket was located in the middle of London Bridge and, as the name suggests, was dedicated to the ill-fated archbishop of Canterbury.

Founded in 1205, the stone chapel was among the first buildings constructed on the bridge by priest-architect Peter de Colechurch in 1176, who was actually buried beneath the chapel (for more on him and the construction of the bridge, see our earlier posts here and here).

Founded in 1205, the stone chapel was among the first buildings constructed on the bridge by priest-architect Peter de Colechurch in 1176, who was actually buried beneath the chapel (for more on him and the construction of the bridge, see our earlier posts here and here).

Facing downstream and located on a wider than normal pier – the 11th pier from the Southwark end of the bridge and the ninth from the City end – the original chapel was built in the early English Gothic style and consisted of an upper chapel with a groined roof and columns and vaulted lower chapel or undercroft. Standing some 40 foot high, it would have towered over the shops and residences on the bridge. There is some suggestion it was damaged by fire in 1212 and may have had to have been extensively repaired.

It’s name ensured its popularity – Becket was martyred in Canterbury Cathedral in 1170, apparently on the orders of King Henry II, and, canonised just three years later, had quickly become the focus of a popular religious cult in his home town of London. The chapel also became renowned as a wayside stop for pilgrims to receive the saint’s blessing before making their way to Canterbury where his shrine was located.

But it wasn’t just pilgrims who had an attachment – the chapel was apparently popular among watermen who, when the tide allowed them, were known to tie up their craft on the chapel pier and ascend to the undercroft through a lower entrance.

The chapel – which apparently had two priests at the beginning as well as a number of clerks although the number of priests is known to have climbed as high as five in the 14th century – was nominally under the control of the priest of the church of St Magnus-the-Martyr, located at the City end of the bridge. The reality seems to have been however, that the priests and other “Brothers of the Bridge” enjoyed considerable freedom in their roles, including, after 1483, obtaining the right keep alms taken during services provided he made a generous contribution to the parish finances. Like most who worked on the bridge, the priests and “clerks of the chapel” would likely have lived on it.

Relics housed in the chapel apparently included fragments of the True Cross and a number of chantries were built inside the chapel in the 14th century – it’s believed this may have led to some overcrowding and been one of the reasons for a major rebuilding of the chapel – this time in the Perpendicular Gothic style – between 1384 and 1397.

The chapel survived until the Dissolution when, in 1548, the priest was ordered to close it up and it was desecrated and later converted into a dwelling (later still, parts of it were used as a warehouse). It was demolished over succeeding years – by the late 18th century just the lower chapel remained – with the final remnants removed in the early 1800s.

Some bones in a small casket were disinterred in from the chapel undercroft during this process in the early 19th century. Although these were rumoured to be those of de Colechurch, analysis found them to be part of a human arm bone, a cow bone and goose bones. (Other accounts suggest most of Peter’s bones were tossed into the Thames and that a small number were even sold at auction).

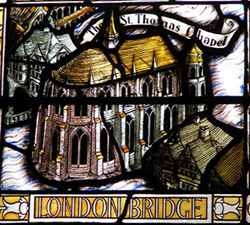

There’s a stained glass window commemorating the bridge in St Magnus-the-Martyr Church today (pictured above).

This Week in London – Party like a Georgian; a playground with a history; and, a Dickens whodunnit…

• Join the Georgian Queen Caroline for a garden party in the grounds of Kensington Palace this weekend. The Georgian Court will be taking to the palace gardens for a summer celebration featuring music, military drills and theatre as they bring the era to life. Visitors are encouraged to immerse themselves in the experience as a courtier with the gardens decked out in a range of tents where they can try out costumes and powdered wigs as well as learn court etiquette, swordplay and dancing while the ice-house will feature Georgian ice-cream (and it’s rather odd flavours such as parmesan). Runs from tomorrow until Sunday. Admission charges apply (under 16s go free with a maximum of six children per paying adult). For more, see www.hrp.org.uk/KensingtonPalace/. PICTURE: ©Historic Royal Palaces

• Join the Georgian Queen Caroline for a garden party in the grounds of Kensington Palace this weekend. The Georgian Court will be taking to the palace gardens for a summer celebration featuring music, military drills and theatre as they bring the era to life. Visitors are encouraged to immerse themselves in the experience as a courtier with the gardens decked out in a range of tents where they can try out costumes and powdered wigs as well as learn court etiquette, swordplay and dancing while the ice-house will feature Georgian ice-cream (and it’s rather odd flavours such as parmesan). Runs from tomorrow until Sunday. Admission charges apply (under 16s go free with a maximum of six children per paying adult). For more, see www.hrp.org.uk/KensingtonPalace/. PICTURE: ©Historic Royal Palaces

• First created in 1923, a playground in Victoria Tower Gardens – newly named the Horseferry Playground – has been reopened after improvement works. The works, carried out under the management of Royal Parks, have seen the reintroduction of a sandpit as well as the installation of new swings and slide, dance chimes and a stare play installation to represent the River Thames. The playground, located close to the Houses of Parliament in Westminster, also features a series of timber horse sculptures, new seating and a refreshment kiosk with metal railings designed by artist Chris Campbell depicting events such as the Great Fire of London and Lord Nelson’s funeral barge and views of the River Thames. The project has also seen the Spicer Memorial, commemorating role of paper merchant and philanthropist Henry Spicer in the establishment of the playground – then just a large sandpit, restored. For more, see www.royalparks.org.uk/parks/victoria-tower-gardens.

• Now On – A Dickens Whodunnit: Solving the Mystery of Edwin Drood. This temporary exhibition at the Charles Dickens Museum in Bloomsbury explores the legacy of Dickens’ final novel The Mystery of Edwin Drood, left unfinished after his death in 1870. Visitors are able to investigate crime scenes, search for murder clues and see the table on which the novel was penned as well as clips from theatrical adaptations, and a wealth of theories on ‘whodunit’. The exhibition runs until 11th November. Admission charge applies. For more, see www.dickensmuseum.com.

Send all items for inclusion to exploringlondon@gmail.com.

Famous Londoners – Sir Hugh Myddelton…

The Welsh-born “merchant adventurer” Sir Hugh Myddelton (also spelt Myddleton or Middleton) is best remembered in London for the construction of the New River, a water engineering project which still provides some of city’s water.

Born about 1560, the sixth son (and one of 16 children) of Richard Myddelton, governor of Denbigh Castle in Wales, Hugh Myddelton travelled to London to seek his fortune and there became apprenticed to a goldsmith before himself becoming a member of the Goldsmith’s Company in 1592 (he later became warden of the company).

Born about 1560, the sixth son (and one of 16 children) of Richard Myddelton, governor of Denbigh Castle in Wales, Hugh Myddelton travelled to London to seek his fortune and there became apprenticed to a goldsmith before himself becoming a member of the Goldsmith’s Company in 1592 (he later became warden of the company).

Operating out of premises in Bassishaw (now Basinghall Street), he gained a reputation among the wealthy and nobility for his work and was appointed Royal Jeweller to King James I (he had apparently also supplied jewellery to Queen Elizabeth I).

Myddelton became a wealthy merchant and banker, and, in 1603, he also succeeded his father as MP for Denbigh Borough, a post he held repeatedly until 1628.

Sir Hugh became one of the driving forces behind the New River project which aimed to address the strain on London’s water sources by bringing clean water from the River Lea in Hertfordshire via a 39 mile-long canal to New River Head in London.

After an aborted earlier attempt to build a canal from Hertfordshire to London (which had run into financial difficulties), Sir Hugh was granted authority to carry out the works for the New River in 1609 and employed mathematicians like Edward Pond and Edward Wright to direct the course with the man behind the earlier attempt, Edmund Colthurst, overseeing the works.

By 1611 it became clear to Myddelton that he wouldn’t have the necessary funds to complete the works so he obtained the financial aid of the king (in return the king was to get half of all profits).

The project was eventually completed in 1613 and a ceremony was held at the New River Head in Islington where the canal then terminated (just south of where Sadler’s Wells Theatre now stands).

Myddelton, who continued to diversify in business and made considerable sums from his ownership of lead and silver mines in Wales as well as from a land reclamation project on the Isle of Wight, became the first governor of the New River Company when it was created by royal charter in 1619 and remained a key figure in it until his death. He was created a baronet in 1622.

Myddelton, who married twice, had 15 or more children to his second wife – only about half of whom survived him. He died on 7th December, 1631, and was buried in the now demolished St Matthew Friday Street where he had been a church warden (some of his children were buried there as well). One of his brothers, Sir Thomas Myddelton, was a Lord Mayor of London.

Among memorials to Sir Hugh in London is a statue of him on Islington Green which was unveiled in 1872 by William Gladstone, later PM. There is also a statue of him on the Royal Exchange (pictured) and a number of Islington streets have been named for him.

For more on London’s historic water sources, see London’s Lost Rivers: A Walker’s Guide.

Treasures of London – ‘Timepiece’, Thames embankment…

In honour of the sun and the heatwave it’s brought this summer, here’s the giant “equinoctial” sundial on the north bank of the Thames, just east of Tower Bridge. Known as Timepiece, it is the work of London-based sculptor Wendy Taylor and was installed here, beside the lock that leads into St Katharine Docks, in 1973. Measuring more than 3.5 metres across, the dial is made from stainless steel and is supported by three chunky chain link cables. According to the plaque, it was commissioned by Strand Hotels Ltd. It’s now a Grade II-listed structure.

10 sites from London at the time of the Magna Carta – 8. Bermondsey Abbey…

Bermondsey Abbey, which was more than 130-years-old by the time King John put his seal to the Magna Carta in 1215, has an unusual connection to the unpopular king – it is one of a number of buildings in London which has, at various times in history, been erroneously referred to as King John’s Palace.

Bermondsey Abbey, which was more than 130-years-old by the time King John put his seal to the Magna Carta in 1215, has an unusual connection to the unpopular king – it is one of a number of buildings in London which has, at various times in history, been erroneously referred to as King John’s Palace.

This suggestion – that it was a palace which was later converted into an abbey – may have arisen from a site on the former abbey grounds being known at some point in its history as King John’s Court (that name was said to commemorate the fact that King John visited the abbey).

Putting how King John’s name came to be linked with the abbey aside, we’ll take a quick look at the history of the abbey which rose to become an important ecclesiastical institution in medieval times.

While there was a monastic institution in Bermondsey as far back as the early 8th century, the priory which was here during the reign of King John was founded in 1082, possibly on the site of the earlier institution, by a Londoner named as Aylwin Child(e), apparently a wealthy Saxon merchant who was granted the land by King William the Conqueror.

In 1089, the monastery – located about a mile back from the river between Southwark and Rotherhithe – became the Cluniac Priory of St Saviour, an order centred on the French abbey of Cluny, and was endowed by King William II (William Rufus) with the manor of Bermondsey.

It was “naturalised” – that is, became English – by the first English prior, Richard Dunton, in 1380, who paid a substantial fine for the process. It was elevated to the status of an abbey by Pope Boniface IX in 1399.

It had some important royal connections – King John’s father, King Henry II and his wife Queen Eleanor celebrated Christmas here in 1154 (their second child, the ill-fated Henry, the young King, was born here a couple of months later), and Queen Catherine (of Valois), wife of King Henry V, died here in 1437. It was also at Bermondsey Abbey that Elizabeth Woodville, the widow of King Edward IV and mother of the two “Princes in the Tower”, died in 1492 following her retirement from court.

The abbey, which grew to have an enormous income thanks to its acquisition of property in a range of counties, survived until the Dissolution when, in 1537, King Henry VIII closed its doors. It was later acquired by Sir Thomas Pope who demolished the abbey and built a mansion for himself on the site (and founded Trinity College in Oxford apparently using revenues from the property). We’ll deal more with its later history in an upcoming post.

The ruins of the abbey were extensively excavated in the past few decades and some of the remaining ruins of the abbey can still be seen buildings around Bermondsey Square and a blue plaque commemorating the abbey was unveiled in 2010. Bermondsey Street runs roughly along the line of the path which once led from the abbey gates to the Thames and the abbey had a dock there still commemorated as St Saviour’s Dock. The abbey’s name is commemorated in various streets around the area.

For more on the history of the Magna Carta, see David Starkey’s Magna Carta: The True Story Behind the Charter.

PICTURE: An archaeological dig at the ruins of Bermondsey Abbey in 2006. Zefrog/Wikipedia.

Famous Londoners – Peter de Colechurch…

We recently ran a piece on the building of the first stone London Bridge (see our earlier post here) and so we thought it timely to take a look at the life of the builder, priest and ‘architect’ Peter de Colechurch.

Not a lot is known about the life of de Colechurch – although we do know he took his name from the fact he the chaplain of St Mary Colechurch, a church which once stood at the junction of Poultry and Old Jewry (and was destroyed in the Great Fire of 1666).

The stone London Bridge wasn’t his first attempt at bridge-building – in 1163 he had supervised the rebuilding of the wooden London Bridge after a fire some 30 years before.

His role in building the subsequent stone bridge remains a little unclear but he was known to have been in charge of the building works themselves and also headed the fundraising and it is believed he headed a guild responsible for the upkeep of the bridge known as the Fraternity of the Brethren of London Bridge.

His seal depicts a priest celebrating mass at an altar with the Latin Sigillum Petri Sacerdotis Pontis Londoniarum (Seal of Peter Priest of London Bridge).

The chapel on the bridge was dedicated to St Thomas á Becket and it’s suggested that he and de Colechurch would have known each other – Becket had been christened at St Mary Colechurch in 1118.

Sadly, de Colechurch did not live to see the stone London Bridge completed – he died in 1205 and was buried under the floor of the chapel on the bridge.

Some bones in a small casket were disinterred in from the chapel undercroft in 1832 – now in the Museum of London, these were rumoured to be those of de Colechurch although after analysis the bones were found to be part of a human arm bone, a cow bone and goose bones. (Other accounts suggest most of Peter’s bones were tossed into the Thames and a small number sold at auction).

10 sites from London at the time of the Magna Carta – 7. Old London Bridge…

The current London Bridge, which spans the River Thames linking Southwark to the City, is just the latest in several incarnations of a bridge which originally dates back to Roman times.

This week, we’re focusing on first stone bridge to be built on the site. Constructed over a period of some 33 years, it was only completed in 1209 during the reign of King John, some six years before the signing of the Magna Carta.

Construction on the bridge began in 1176, only 13 years after the construction of an earlier wooden bridge on the site (the latest of numerous wooden bridges built on the site, it had apparently built of elm under the direction of Peter de Colechurch, chaplain of St Mary Colechurch, a now long-gone church in Cheapside).

It was the priest-architect de Colechurch who was also responsible for building the new bridge of stone, apparently on the orders of King Henry II. While many of the wealthy, including Richard of Dover, the Archbishop of Canterbury, gave funds for the construction of the bridge, a tax was also levied on wool, undressed sheepskins and leather to provide the necessary monies – the latter led to the phrase that London Bridge was “built upon woolpacks”. King John, meanwhile, had decreed in 1201 that the rents from several homes on the bridge would be used to repair it into perpetuity.

The bridge, which featured 20 arches – a new one built every 18 months or so, was apparently constructed on wooden piles driven into the river bed at low water with the piers of Kentish ragstone set on top. It was dangerous work and it’s been estimated that as many as 200 men may have died during its construction.

The bridge was almost completely lined with buildings on both sides of the narrow central street. These included a chapel dedicated to St Thomas á Becket – a stopping point for pilgrims heading to the saint’s shrine in Canterbury, as well as shops and residences (although, apart from the chapel, we know little about the original buildings). There was also a drawbridge toward the southern end and the Great Stone Gate guarding the entrance from Southwark.

Peter de Colechurch died in 1205, before the bridge was completed. He was buried in the undercroft of the chapel on the bridge.

Three men subsequently took on the task of completing the bridge – William de Almaine, Benedict Botewrite and Serle le Mercer who would go on to be a three time Lord Mayor of London. All three were later bridge wardens, the City officials charged with the daily running of the bridge itself.

One of key events on the bridge in the years immediately after its completion was the arrival of Louis, the Dauphin of France, in May, 1216. Louis had been invited to depose John by the rebellious barons after the agreement sealed at Runnymede fell apart and in 1216, he and his men marched over London Bridge on their way to St Paul’s Cathedral. (We’ll deal with this in more detail in a later post).

What became known as ‘Old London Bridge’, which stood in line with Fish Street Hill, survived the Great Fire of 1666, albeit badly damaged, but was eventually replaced with a new bridge, known, unsurprisingly as ‘New London Bridge’, which opened in 1831. Designed by John Rennie, this bridge was later replaced by one which opened in 1971 (Rennie’s bridge was sold off and now stands in Lake Havasu City, Arizona).

For a detailed history of Old London Bridge, check out Old London Bridge: The Story of the Longest Inhabited Bridge in Europe.

What’s in a name?…Waterloo…

Given the recent commemorations surrounding the bicentenary of the Battle of Waterloo (including a re-enactment of the arrival of news of Wellington’s victory in London where it was delivered to the Prince Regent), we thought it only fitting to take a look at the use of the name in London.

The name Waterloo, which now refers to a district in Lambeth centred on Waterloo Station, was first used to designate the bridge which crosses the Thames here.

Opened in 1817 as a toll bridge, the John Rennie-designed structure was known as Strand Bridge during its construction but renamed Waterloo at its opening two years after the battle. (Rennie’s bridge was later demolished and rebuilt in the 20th century – the current bridge is pictured above).

The name was also used to designate Waterloo Road and in the early 1820s was given to the church St John’s Waterloo (now St John’s and St Andrew’s at Waterloo) located on the road.

In 1848, Waterloo Station opened and it was after this that the surrounding district, known in past ages for its swampiness (hence streets like Lower Marsh), generally became known as Waterloo.

Landmarks in the Waterloo district include the historic Old Vic Theatre, which opened in 1818, and the Young Vic Theatre as well as the Lower Marsh Market.

On 3rd July, Waterloo will host the Waterloo Carnival with a picnic on Waterloo Millennium Green and a procession (for more on that, see www.waterlooquarter.org/news/come-and-support-this-years-waterloo-carnival) while the month-long Waterloo Food Festival kicks on on 1st July. For more on events in Waterloo commemorating bicentenary, see www.wearewaterloo.co.uk/waterloo200/.

Treasures of London – Waterloo Memorial…

Unveiled earlier this month at Waterloo Station to mark the bicentenary of the Battle of Waterloo, the memorial features a supersized solid bronze replica of the obverse side of the Waterloo Campaign medal depicting Nike, the Greek goddess of victory.

Unveiled earlier this month at Waterloo Station to mark the bicentenary of the Battle of Waterloo, the memorial features a supersized solid bronze replica of the obverse side of the Waterloo Campaign medal depicting Nike, the Greek goddess of victory.

The memorial, which was installed on a balcony above the main concourse by The London Mint Office on behalf of Waterloo200 – the organisation overseeing bicentenary commemorations, is dedicated to the 4,700 members of the allied armies who were killed in the battle on 18th June, 1815 (which also left 14,600 wounded and 4,700 missing).

The upsized medal, which has a diameter of 65 centimetres, is a replica of one which was the first to be commissioned for every soldier who fought in the battle, regardless of their rank.

Designed by London-based artist Jason Brooks, the memorial also features a famous quote from the Duke of Wellington on granite: “My heart is broken by the terrible loss I have sustained in my old friends and companions and my poor soldiers. Believe me, nothing except a battle lost can be half so melancholy as a battle won.”

It was unveiled on 10th June by the 9th Duke of Wellington (pictured with the memorial) in a ceremony attended by some of the descendants of those who fought and died in the battle.

Waterloo Station was itself, of course, named in commemoration of the battle (well, indirectly – it, like the surrounding district itself, took its name from nearby Waterloo Bridge which was in fact named after the battle).

LondonLife – Battersea in rebirth…

Work continues on repurposing the former Battersea Power Station as part of the £15 billion Nine Elms project that will create a whole new precinct located on the south bank of the Thames. Photographer Ian Wylie recently captured the work in progress. He writes: “I’ve been keeping an eye on the huge redevelopment of the entire Nine Elms area, including the new American Embassy quarter and the Battersea Power Station development. Also noticing the work going on to remove, rebuild and replace the four iconic power station chimneys as seen from other London viewpoints, including this one: flic.kr/p/rpGocV. So (these) photos were simply a result of another walk around the area where so much is changing so fast and yet reminders of London’s past still remain, such as this very old street sign: flic.kr/p/tQVY9W. It’s not an area that attracts a large number of visitors but it was interesting to see a few people walking around, just as I was, obviously also intrigued by the past, present and future of this site.” For more on the project, see www.batterseapowerstation.co.uk and www.nineelmslondon.com.

Work continues on repurposing the former Battersea Power Station as part of the £15 billion Nine Elms project that will create a whole new precinct located on the south bank of the Thames. Photographer Ian Wylie recently captured the work in progress. He writes: “I’ve been keeping an eye on the huge redevelopment of the entire Nine Elms area, including the new American Embassy quarter and the Battersea Power Station development. Also noticing the work going on to remove, rebuild and replace the four iconic power station chimneys as seen from other London viewpoints, including this one: flic.kr/p/rpGocV. So (these) photos were simply a result of another walk around the area where so much is changing so fast and yet reminders of London’s past still remain, such as this very old street sign: flic.kr/p/tQVY9W. It’s not an area that attracts a large number of visitors but it was interesting to see a few people walking around, just as I was, obviously also intrigued by the past, present and future of this site.” For more on the project, see www.batterseapowerstation.co.uk and www.nineelmslondon.com.

10 sites from London at the time of the Magna Carta – 4. Thorney Island…

Both Westminster Abbey and the Palace of Westminster (these days better known as the Houses of Parliament – pictured) pre-date 1215 but unlike today in 1215 the upon which they stood was known as Thorney Island.

Both Westminster Abbey and the Palace of Westminster (these days better known as the Houses of Parliament – pictured) pre-date 1215 but unlike today in 1215 the upon which they stood was known as Thorney Island.

Formed by two branches of the Tyburn River as they ran down to the River Thames, Thorney Island (a small, marshy island apparently named for the thorny plants which once grew there) filled the space between them and the Thames (and remained so until the Tyburn’s branches were covered over).

One branch entered the Thames in what is now Whitehall, just to the north of where Westminster Bridge; another apparently to the south of the abbey, along the route of what is now Great College Street. (Yet another branch apparently entered the river near Vauxhall Bridge).

The abbey’s origins go back to Saxon times when what was initially a small church – apparently named after St Peter – was built on the site. By 960AD it had become a Benedictine monastery and, lying west of what was then the Saxon city in Lundenwic, it become known as the “west minster” (St Paul’s, in the city, was known as “east minster”) and a royal church.

The origins of the Palace of Westminster don’t go back quite as far but it was the Dane King Canute, who ruled from 1016 to 1035, who was the first king to build a palace here. It apparently burnt down but was subsequently rebuilt by King Edward the Confessor as part of a grand new palace-abbey complex.

For it was King Edward, of course, who also built the first grand version of Westminster Abbey, a project he started soon after his accession in 1042. It was consecrated in 1065, a year before his death and he was buried there the following year (his bones still lie inside the shrine which was created during the reign of King Henry III when he was undertaking a major rebuild of the minster).

Old Palace Yard dates from Edward’s rebuild – it connected his palace with his new abbey – while New Palace Yard, which lies at the north end of Westminster Hall, was named ‘new’ when it was constructed with the hall by King William II (William Rufus) in the late 11th century.

Westminster gained an important boost in becoming the pre-eminent seat of government in the kingdom when King Henry II established a secondary treasury here (the main treasury had traditionally been in Winchester, the old capital in Saxon times) and established the law courts in Westminster Hall.

King John, meanwhile, followed his father in helping to establish London as the centre of government and moved the Exchequer here. He also followed the tradition, by then well-established, by being crowned in Westminster Abbey in 1199 and it was also in the abbey that he married his second wife, Isabella, daughter of Count of Angouleme, the following year.

10 sites from London at the time of the Magna Carta – 3. The Temple…

Not much remains today of the original early medieval home of the Templar Knights which once existed just west of the City of London. While the area still carries the name (as seen in the Underground station, Temple), most the buildings now on the site came from later eras. But there are some original elements.

First though, a bit of history. The Templar precinct which become known as the Temple area of London was the second site in the city given to the military order, known more completely as the Knights of the Temple of Solomon (thanks to their Jerusalem HQ being located near the remains of the Temple of Solomon).

The first was in Holborn, located between the northern end of Chancery Lane and Staple Inn, and was known as the ‘Old Temple’ after which, in the latter years of the 12th century, the Templars moved their headquarters to the new site – ‘New Temple’ or Novum Templum – on unoccupied land on the bank of the River Thames.

The first was in Holborn, located between the northern end of Chancery Lane and Staple Inn, and was known as the ‘Old Temple’ after which, in the latter years of the 12th century, the Templars moved their headquarters to the new site – ‘New Temple’ or Novum Templum – on unoccupied land on the bank of the River Thames.

This new precinct included consecrated and unconsecrated areas. The consecrated part was a monastery and was located around what is now Church Court with the monastic refectory built on the site of what is now Inner Temple Hall – the medieval buttery is the only part of the original building which survives.

The lay or unconsecrated part of the precinct lay east of Middle Temple Lane, where a second hall was built on the site of what is now the Middle Temple Hall (you’ll find more on that here) which was used to house the lay followers of the order.

The original buildings also included the still existing Templar Church (pictured, along with a monument depicting the Templars outside the church), which was consecrated in 1185 during the reign of King Henry II by Heraclius, the Patriarch of Jerusalem, on a visit to London. Like all other Templar churches, its circular design was based on the design of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem (the chancel was added later and consecrated in the presence of King Henry III in 1240 – for more on the Temple Church, you can see our earlier post here.

The New Temple become an important site in London (and the kingdom as a whole – the Masters of the Temple were the heads of the order in England) and was used by many of the nobility as a treasury to store valuables (and to lend money). It also had close connections with the monarchy and was, as we saw earlier this week, a power base for King John and from where he issued what is known as the King John Charter in 1215. He also used it for a time as a repository for the Crown jewels.

In an indication of the Temple’s prominence in state affairs, some of the great and powerful were buried here during this period including William Marshal, 1st Earl of Pembroke, who died in 1219, and his sons William and Gilbert (for more on those buried in the Temple, see our earlier post here). There were also apparently plans to bury King Henry III and his Queen here – this apparently spurred on the building of the chancel on the church – but they were eventually buried in Westminster Abbey instead.

Numerous relics were also apparently housed here during the Templar times including a phial believed to contain Christ’s blood and pieces of the true Cross.

The Templar era came to an end in 1312 when the order was dissolved on the authority of Pope Clement V amid some heinous allegations of blasphemy and sexual immorality which had the support of King Philip IV of France. While the pope awarded their property to the rival order, the Knights of the Hospital of St John of Jerusalem (also known as the Hospitallers), King Edward II had other ideas and ignored their claims with regard to the London property and instead, claimed it for the Crown (a dispute which went on for some years).

It later became associated particularly with lawyers, although lawyers would have certainly been at work in the New Temple given its role as banker to the wealthy (but more on its later associations with lawyers in later post).

For more on the history of the Templars, see Malcolm Barber’s The New Knighthood: A History of the Order of the Temple.

London Pub Signs – The Knights Templar…

Located in a former bank at the corner of Chancery Lane and Carey Street, this pub takes its name from the Crusader order known as the Knights Templar who once owned the land upon which the lane was constructed.

The Knights Templar was founded in Jerusalem in 1118 to protect Christian pilgrims and took its name from the Temple of Solomon upon the remains of which its headquarters in Jerusalem was built.

The order arrived in London later that century and Chancery Lane was created to connect the site of their original headquarters in Holborn with their subsequent home which lay between Fleet Street and the Thames – with the latter centred on a chapel (consecrated in 1185) which still stands and is now known as the Temple Church.

The pub, which opened in 1999, was formerly the home of the Union Bank of London Ltd, built in 1865 to the design of architect FW Porter.

Original features inside the Grade II-listed building – built in the ‘high Renaissance’-style – include cast iron columns and ornate detailing.

It is now part of the Wetherspoon’s chain. For more information, see www.jdwetherspoon.co.uk/home/pubs/the-knights-templar-chancery-lane.

This Week in London – The Boat Race; Designs of the Year; Heckling Hitler; and Victorian-era homelessness…

• The 161st Boat Race is on this weekend and will once more see Oxford and Cambridge rowing crews battling it out in their annual contest on the Thames. The day’s schedule of festivities kicks off at noon at Bishop’s Park near the race’s starting point just west of Putney Bridge and at Furnivall Gardens near Hammersmith Bridge but the main highlights don’t take place until late in the afternoon – the Newton Women’s Boat Race at 4.50pm and the main event, the BNY Mellon Boat Race, at 5.50pm. The race runs along the Thames from Putney Bridge through to Chiswick Bridge with plenty of vantage points along the way. The tally currently sits at 78 to Oxford and 81 to Cambridge. For more information, including where to watch, head to http://theboatraces.org/.

• Prospective “Designs of the Year” are on display at the Design Museum in Shad Thames ahead of the announcement of awards in May and June. With the awards – handed out in six categories – now in their eighth year, the 76 designs on display include Google’s self-driving car, the Frank Gehry-designed Foundation Louis Vuitton in Paris and Asif Kahn’s experimental architectural installation Megafaces which debuted at the Sochi Olympics as well as Norwegian banknotes, a billboard that cleans pollutants from the air and a book printed without ink. Runs until 23rd August. Admission charge applies. For more, see www.designmuseum.org/exhibitions/designs-of-the-year-2015.

• On Now: Heckling Hitler: World War II in Cartoon and Comic Art. Showing at the Cartoon Museum in Bloomsbury, this exhibition explores how World War II unfolded through the eyes of British cartoonists. It features more than 120 original drawings and printed ephemera and while the focus is largely on those contained newspapers and magazines, the exhibition does include some sample materials from books, aerial leaflets, artwork from The Dandy and The Beano, postcards and overseas propaganda publications as well as some unpublished cartoons drawn in prisoner-of-war camps and by civilians at home (the latter on scrap paper from the Ministry of Food), and even a rare pin cushion featuring Hitler and Mussolini. Among the artists whose works are featured are ‘Fougasse’ (creator of Ministry of Information posters reminding the public that ‘Careless Talk Costs Lives’), William Heath Robinson and Joe Lee. The exhibition runs until 12th July. Admission charge applies. For more, see www.cartoonmuseum.org/exhibitions/current-exhibitions/heckling-hitler.

• On Now: Homes of the Homeless: Seeking Shelter in Victorian London. This exhibition at the Geffrye Museum in Shoreditch explores the places inhabited by London’s poor during the 19th and 20th centuries and brings them to life through paintings, photographs and objects as well as the retelling of personal stories and reports. Starting in the 1840s, the exhibition charts the problems faced by London’s poor and examines the dirty and cramped conditions of lodging houses, workhouses and refuges where they took shelter along with, for those even less fortunate, the streets where they slept rough before moving on to some of the housing solutions designed specifically to help the poor. Runs until 12th July. Admission charge applies. Running alongside the exhibition is a free display, Home and Hope – a collaborative exhibition with the New Horizon Youth Centre which explores the experience of young homeless people in London today. For more, see www.geffrye-museum.org.uk/whatson/exhibitions-and-displays/homes-of-the-homeless/.

Send all items for inclusion to exploringlondon@gmail.com

What’s in a name?…Lambeth…

The origins of the Thames-side district Lambeth’s name are not as obscure as it might at first seem.

The origins of the Thames-side district Lambeth’s name are not as obscure as it might at first seem.

First recorded in the 11th century, the second part of the name – which apparently is related to/a derivative of the word ‘hithe’ or ‘hythe’ – means a riverside landing place while the first part of the name is exactly what it seems – ‘lamb’. Hence, Lambeth was a riverside landing or shipping place for lambs and cattle.

There has apparently been a suggestion in the past that the word ‘lamb’ actually derived from an Old English word meaning muddy place, hence the meaning was ‘muddy landing place’. That theory, however, is now generally discounted.

Lambeth these days is still somewhat in the shadow of the much more famous Westminster river bank opposite but among its attractions is the Imperial War Museum (located in the former Bethlem Hospital, see our earlier post here), Lambeth Palace (pictured above) – London residence of the Archbishop of Canterbury, and, of course, the promenade of Albert Embankment (sitting opposite Victoria Embankment).

The headquarters of MI6 is also located here in a 1994 building designed by Terry Farrell (among its claims to fame is its appearance in the opening scenes of the James Bond film, The World Is Not Enough).

Lambeth – the name is also that of the borough in which the district is located – was formerly home to the Vauxhall Pleasure Gardens which closed in the mid 19th century (see our earlier post here).

Lost London – Baynard’s Castle (part 2)…

Having previously looked at the Norman fortification (razed by King John in 1213 – see our earlier post here), this time we’re taking a look at the later (medieval) fortification known as Baynard’s Castle.

In the 1300s, a mansion was constructed about 100 metres east of where the castle had originally stood on a riverfront site which had been reclaimed from the Thames. This was apparently destroyed by fire before being rebuilt in the 1420s and it became the seat of the House of York during the Wars of the Roses. King Edward IV was proclaimed king here in 1461 and King Richard III was offered the crown here in 1483 (a moment famously captured by William Shakespeare).

In the 1300s, a mansion was constructed about 100 metres east of where the castle had originally stood on a riverfront site which had been reclaimed from the Thames. This was apparently destroyed by fire before being rebuilt in the 1420s and it became the seat of the House of York during the Wars of the Roses. King Edward IV was proclaimed king here in 1461 and King Richard III was offered the crown here in 1483 (a moment famously captured by William Shakespeare).

King Henry VII transformed the fortified mansion into a royal palace at the start of the 16th century – adding a series of towers – and his son, King Henry VIII, gave it to the ill-fated Catherine of Aragon when they married. The Queen subsequently took up residence (Anne Boleyn and Anne of Cleves also resided here when queen – the latter was the last member of the royal family to use it as a permanent home).

After King Henry VIII’s death, the palace passed into the hands of the Earl of Pembroke (brother-in-law of Queen Catherine Parr, Henry’s surviving Queen) who substantially extended it, adding ranges around a second courtyard. In 1553, both Lady Jane Grey and Queen Mary I were proclaimed queen here. Queen Elizabeth I was another royal visitor to the palace, entertained with a fireworks display when she did.

It was left untouched during the Civil War (the Pembrokes were Parliamentarians) but following the Restoration, it was occupied by the Royalist Earl of Shrewsbury (among his visitors was King Charles II). It wasn’t to be for long however – the palace was largely destroyed in the Great Fire of 1666, although remnants of the building, including one or two of the towers, continued to be used for various purposes until the site was finally cleared in the 1800s to make way for warehouses.

The site in Queen Victoria Street in Blackfriars (the area is named for the monastery built on the site of the Norman castle) is now occupied by the Brutalist building named Baynard House. The castle is also commemorated in Castle Baynard Street and Castle Baynard Ward.

It was discovered in archaeological excavations in the 197os that the castle’s waterfront wall had been built on top of the Roman riverside city wall.

PICTURE: © Copyright Andrew Abbott

London Pub Signs – The George and Devonshire…

The last remaining pub in old Chiswick village in west London, The George and Devonshire has a history dating back to the 1650s.

Initially known simply as The George (like so many taverns and pubs, apparently after England’s patron saint), by the 1820s the name had changed to The George and Devonshire – the Duke of Devonshire’s former showpiece property, Chiswick House, can still be found nearby (for more on Chiswick House, see our earlier post here). The coat of arms of the Dukes of Devonshire now hang over the door.

Initially known simply as The George (like so many taverns and pubs, apparently after England’s patron saint), by the 1820s the name had changed to The George and Devonshire – the Duke of Devonshire’s former showpiece property, Chiswick House, can still be found nearby (for more on Chiswick House, see our earlier post here). The coat of arms of the Dukes of Devonshire now hang over the door.

The Grade II-listed building at 8 Burlington Lane, which is conveniently located just metres from a Fullers brewery, dates from the 18th century.

There was apparently once a secret passageway which led from the pub under the nearby St Nicholas’ Church (burial place of artist William Hogarth) to an opening located among a group of small cottages near the Thames – it is said to have been used by rum and spirits smugglers in the 1700s. The remains of the entrance can still apparently be seen in the pub’s cellar.

For more, see www.georgeanddevonshire.co.uk.

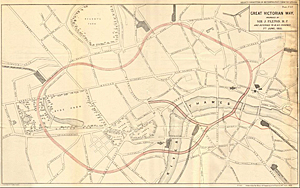

8 structures from the London that never was – 5. Sir Joseph Paxton’s Great Victorian Way…

Fresh from the success of designing The Crystal Palace for the Great Exhibition of 1851 (see our earlier post here), in 1855 Sir Joseph Paxton came up with the idea of building a covered elevated railway “girdle” which would circle parts of central and west London and alleviate traffic congestion.

The proposed 10 mile long, eight track railway – which would feature trains propelled by air pressure (an “atmospheric” system) rather than conventional steam engines and included “express” trains which would only stop at select stations – was to be constructed inside a vast, 108 foot high glass covered arcade which would also contain a road, shopping and even housing.

The proposed 10 mile long, eight track railway – which would feature trains propelled by air pressure (an “atmospheric” system) rather than conventional steam engines and included “express” trains which would only stop at select stations – was to be constructed inside a vast, 108 foot high glass covered arcade which would also contain a road, shopping and even housing.

The trains would travel at such a speed that to get from any one point on the “girdle” to its opposite point would only take 15 minutes.

Paxton presented his proposal to a Parliamentary Select Committee in June 1855 – he had already shown it to Prince Albert whom, he said, “gives it his approval”.

He estimated the cost of his proposal – which he thought would carry some 105,000 passengers every day – at some £34 million – a figure which parliament, which had initially been supportive of the idea, found a little hard to stomach.

This was especially thanks to the fact they were already dealing with the costs of Sir Joseph Bazalgette’s vast sewer system (see our earlier post here), created as a result of the ‘Great Stink’ in 1858 when the smell of untreated human excrement and other waste in the Thames became so strong, parliament had to act.

As a result, the project – which would have crossed the Thames three times, once with a spur line that ended near Piccadilly Circus – never eventuated but the Underground’s Circle Line today follows roughly the same route Paxton’s railway would have.