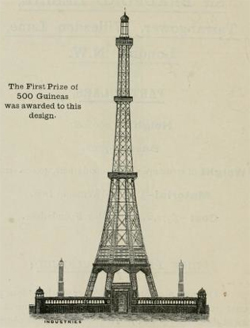

Designed as London’s response to the Eiffel Tower, Watkin’s Tower was the brainchild of railway entrepreneur and MP Sir Edward Watkin.

Following the opening of the Eiffel Tower in 1889, Watkin wanted to go one better in London and build a tower than surpassed its 1,063 feet (324 metres) height.

Following the opening of the Eiffel Tower in 1889, Watkin wanted to go one better in London and build a tower than surpassed its 1,063 feet (324 metres) height.

He apparently first approached Gustave Eiffel himself to design the tower which was to be located as the centrepiece for a pleasure park development at Wembley Park in London’s north (which, incidentally, would be reached by one of Sir Edward’s railway lines – he opened Wembley Park station to service it). But Eiffel declined the offer and Watkin subsequently launched an architectural design competition.

Among the 68 designs received from as far afield as the US and Australia were a cone-shaped tower with a railway spiralling up its exterior, a Gothic-style tower (also with a railway), a tower topped with a 1/12 scale replica of the Great Pyramid, one modelled on the spire of Bow Church in Cheapside and one topped by a giant globe (you can see the catalogue of all entries here).

The winning entry was submitted by Stewart, MacLaren and Dunn who proposed a steel eight legged tower soaring 1,200 feet (366 metres) into the sky. To be lit with electric lighting at night, it came with two observation decks with restaurants, theatres and exhibition space as well as winter gardens, Turkish baths, shops, promenades and a 90 room hotel as well as an astronomical observatory. The top of the tower would be reached by a series of elevators.

The first stage of the project – formally known as London Tower or the Wembley Park Tower – had still not been completed when Wembley Park opened in May, 1894 – standing 154 feet (47 metres tall), it was finally finished in September the following year.

It was to never rise higher. The project become mired in problems – Watkin retired through ill health (and died in 1901), the structure started to subside and the construction company went into liquidation. Dubbed Watkin’s Folly and the London Stump, what there was of the tower was eventually demolished between 1904-1907.

While the dream of the tower never came to be, the site nonetheless became a popular vehicle for recreation and the site was later used for the 1924 British Empire Exhibition with Wembley Stadium built over the spot where the tower had once stood.