• From Peter Rabbit to Aesop’s Fables, animals and their appearance in some of the classics of literature are the subject of a new exhibition which opened at the British Library in St Pancras yesterday. Animal Tales explores the role animals have played in traditional tales around the world along with their importance in the development of children’s literature, and their use in allegorical stories such as CS Lewis’ The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe as well as literary transformations between man and beast (this last in a nod to the fact it’s the centenary of Franz Kafka’s The Metamorphosis). Highlights in the exhibition include one of the first children’s picture books – the 1659 edition of Comenius’ Orbis sensualism pictus, an 18th century woodblock edition of Wu Cheng’en’s Journey to the West, and a soundscape installation drawn from the library’s world leading collection of natural history recordings along with other animal tales from the sound archive. The exhibition, which runs until 1st November, will be accompanied by a series of events. Entry is free (and the display includes a children’s reading area and a family trail brochure). For more, see www.bl.uk. PICTURE: The title page from the 1950 London edition of CS Lewis’ The Lion, the witch and the wardrobe. © CS Lewis Pte Ltd.

• From Peter Rabbit to Aesop’s Fables, animals and their appearance in some of the classics of literature are the subject of a new exhibition which opened at the British Library in St Pancras yesterday. Animal Tales explores the role animals have played in traditional tales around the world along with their importance in the development of children’s literature, and their use in allegorical stories such as CS Lewis’ The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe as well as literary transformations between man and beast (this last in a nod to the fact it’s the centenary of Franz Kafka’s The Metamorphosis). Highlights in the exhibition include one of the first children’s picture books – the 1659 edition of Comenius’ Orbis sensualism pictus, an 18th century woodblock edition of Wu Cheng’en’s Journey to the West, and a soundscape installation drawn from the library’s world leading collection of natural history recordings along with other animal tales from the sound archive. The exhibition, which runs until 1st November, will be accompanied by a series of events. Entry is free (and the display includes a children’s reading area and a family trail brochure). For more, see www.bl.uk. PICTURE: The title page from the 1950 London edition of CS Lewis’ The Lion, the witch and the wardrobe. © CS Lewis Pte Ltd.

• Gladiators will battle it out on the former site of London’s open air Roman amphitheatre in Guildhall Yard this weekend. The shows – which will recreate what gladiatorial games were like in Roman Londinium – will be presided over by an emperor with the crowd asked to pick its side. The ticketed event, being put on by the Museum of London, takes place Friday night from 7pm to 8pm and on Saturday and Sunday, from noon to 1pm and between 3pm and 4pm. Admission charges apply. To book, see www.museumoflondon.org.uk.

• A new International Visitors Victim Service has been launched in London to specifically help foreign nationals affected by crime in the city. The first of its kind in the UK, the service, which has been established by the Metropolitan Police working with independent charity Victim Support and embassies, already operates across the five central London boroughs and is now available through a mobile police kiosk located in the West End’s “impact zone”, an area which spans Leicester Square and Piccadilly Circus (alternatively they can contact the International Visitor Advocates by calling 0207 259 2424 or visit the West End Central Police Station at 27 Savile Row.

• The Mayor of London, Boris Johnson, has celebrated the creation of 100 new pocket parks across London’s 26 boroughs in a scheme which is now being adopted by other locations across the country. The parks range from a rain garden in Vauxhall to a dinosaur playground in Hornsey and have seen more than 25 hectares of community land converted into enhanced green areas. A free exhibition is running at City Hall until 28th August which focuses on the stories of 11 people involved in the creation of the parks. For more on London’s “great outdoors”, you can see an interactive map at www.london.gov.uk/outdoors.

Send all items for inclusion to exploringlondon@gmail.com.

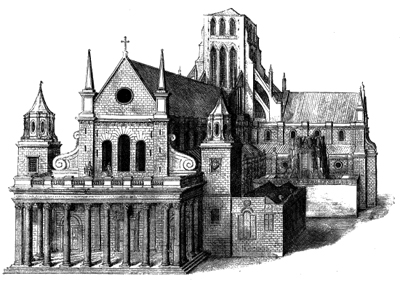

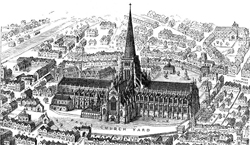

The first was in Holborn, located between the northern end of Chancery Lane and Staple Inn, and was known as the ‘Old Temple’ after which, in the latter years of the 12th century, the Templars moved their headquarters to the new site – ‘New Temple’ or

The first was in Holborn, located between the northern end of Chancery Lane and Staple Inn, and was known as the ‘Old Temple’ after which, in the latter years of the 12th century, the Templars moved their headquarters to the new site – ‘New Temple’ or