Best known as the “Hanging Judge” thanks to his role in the so-called Bloody Assizes of 1685, George Jeffreys climbed the heights of England’s legal profession before his ignominious downfall.

Born on 15th May, 1645, at the family home of Acton Hall in Wrexham, North Wales, Jeffreys was the sixth son in a prominent local family. In his early 20s, having been educated in Shrewsbury, Cambridge and London, he embarked on a legal career in the latter location and was admitted to the bar in 1668.

In 1671, he was made a Common Serjeant of London, and despite having his eye on the more senior role of Recorder of London, was passed over. But his star had certainly risen and, despite his Protestant faith, he was a few years later appointed to the position of solicitor general to James, brother of King Charles II and the Catholic Duke of York (later King James II), in 1677.

In 1671, he was made a Common Serjeant of London, and despite having his eye on the more senior role of Recorder of London, was passed over. But his star had certainly risen and, despite his Protestant faith, he was a few years later appointed to the position of solicitor general to James, brother of King Charles II and the Catholic Duke of York (later King James II), in 1677.

The same year he was knighted and became Recorder of London, a position he had long sought, the following year. Following revelations of the so-called the Popish Plot in 1678 – said to have been a Catholic plot aimed the overthrow of the government, Jeffreys – who was fast gaining a reputation for rudeness and the bullying of defendants – served as a prosecutor or judge in many of the trials and those implicated by what turned out to be the fabricated evidence of Titus Oates (Jeffreys later secured the conviction of Oates for perjury resulting in his flogging and imprisonment).

Having successfully fought against the Exclusion Bill aimed at preventing James from inheriting the throne, in 1681 King Charles II created him a baronet. In 1683 he was made Lord Chief Justice and a member of the Privy Council. Among cases he presided over was that of Algernon Sidney, implicated in the Rye House Plot to assassinate the king and his brother (he had earlier led the prosecution against Lord William Russell over the same plot). Both were executed.

It was following the accession of King James II in February, 1685, that Jeffreys earned the evil reputation that was to ensure his infamy. Following the failed attempt by James Scott, 1st Duke of Monmouth and illegitimate son of the late King Charles II, to overthrow King James II, Jeffreys was sent to conduct the trials of the captured rebels in West Country towns including Taunton, Wells and Dorchester – the ‘Bloody Assizes’.

Of the almost 1,400 people found guilty of treason in the trials, it’s estimated that between 150 and 200 people were executed and hundreds more sent into slavery in the colonies. Jeffreys’, meanwhile, was busy profiting financially by extorting money from the accused.

By now known for his corruption and brutality, that same year he was elevated to the peerage as Baron Jeffreys of Wem and named Lord Chancellor as well as president of the ecclesiastical commission charged with implementing James’ unpopular pro-Catholic religious policies.

His fall was to come only a couple of years later during Glorious Revolution which saw King James II overthrown by his niece, Mary, and her husband William of Orange (who become the joint monarchs Queen Mary II and King William III).

Offered the throne by a coalition of influential figures who feared the creation of a Catholic dynasty following the birth of King James II’s son, James Francis Edward Stuart, William and Mary arrived in England with a large invasion force. King James II’s rule collapsed and he eventually fled the country.

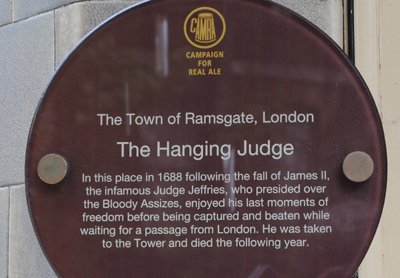

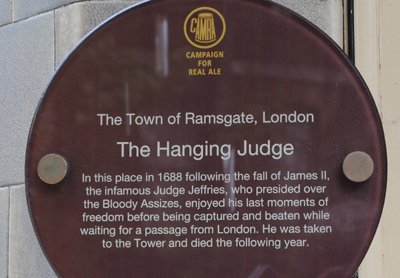

Remaining in London after the king had fled, Lord Jeffreys only attempted to flee as William’s forced approached the city. He made it as far as Wapping where, despite being disguised as a sailor, he was recognised in a pub, now The Town of Ramsgate (pictured above).

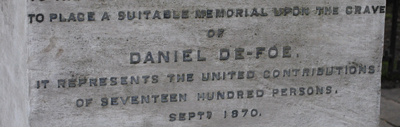

Placed in custody in the Tower of London, he died there of kidney problems on 18th April, 1689, and was buried in the Chapel Royal of Saint Peter ad Vincula (before, in 1692, his body was moved to the Church of St Mary Aldermanbury). All traces of his tomb were destroyed when the church was bombed during the Blitz (for more on the church, see our earlier post here).

Back into the City of London this week and it’s another garden located on the site of a former church.

Back into the City of London this week and it’s another garden located on the site of a former church. The church was among those destroyed in the Great Fire of London in 1666 but, now united with the parish of St Mary Bothaw, was rebuilt to the designs of Sir Christopher Wren shortly after in 1677-88.

The church was among those destroyed in the Great Fire of London in 1666 but, now united with the parish of St Mary Bothaw, was rebuilt to the designs of Sir Christopher Wren shortly after in 1677-88.